In Protest We Trust: Collector Luciano Zuccaccia On The Photobook Exhibition At Fotofestiwal Lodz

-

Published10 Jun 2025

-

Author

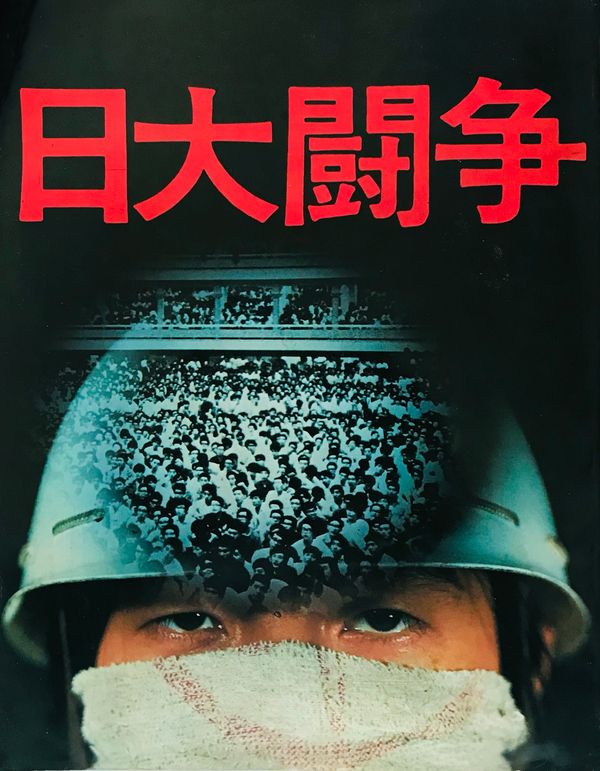

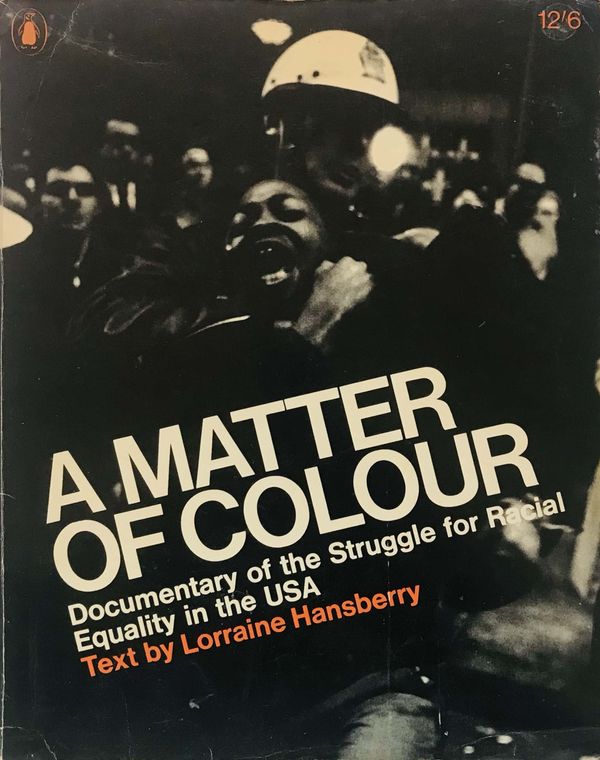

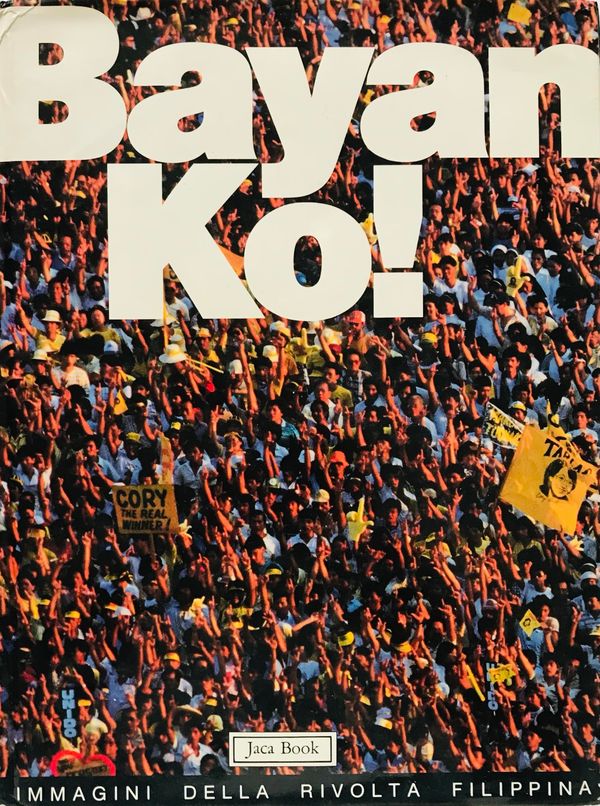

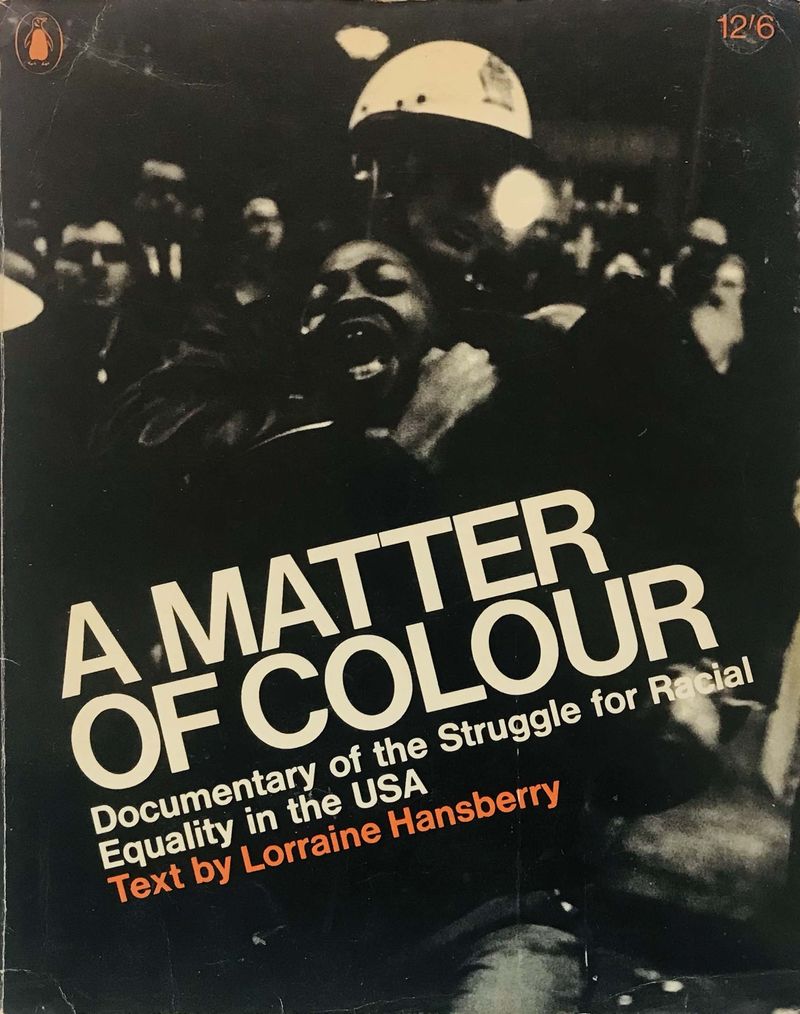

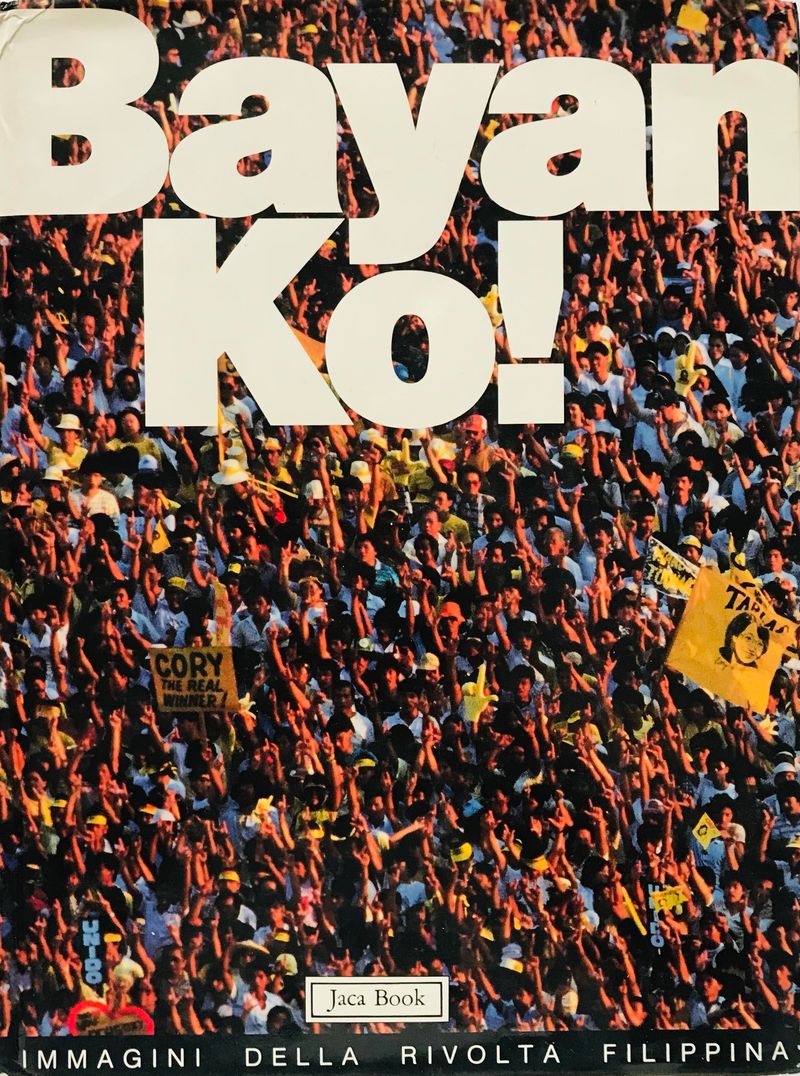

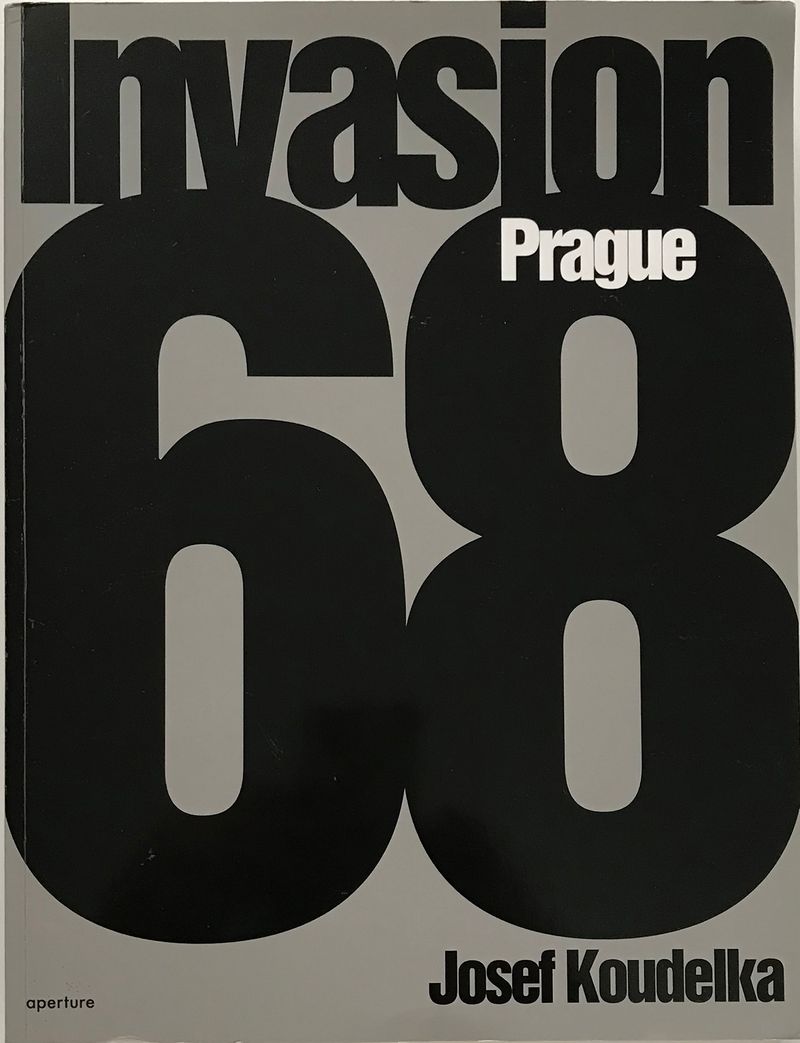

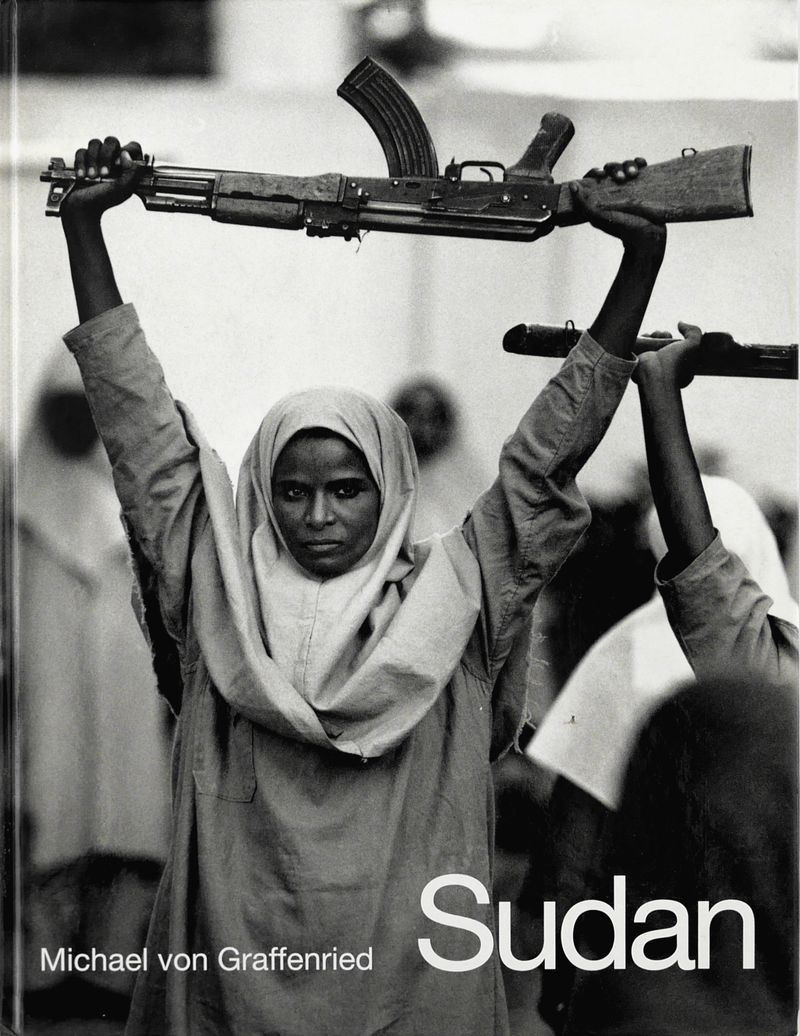

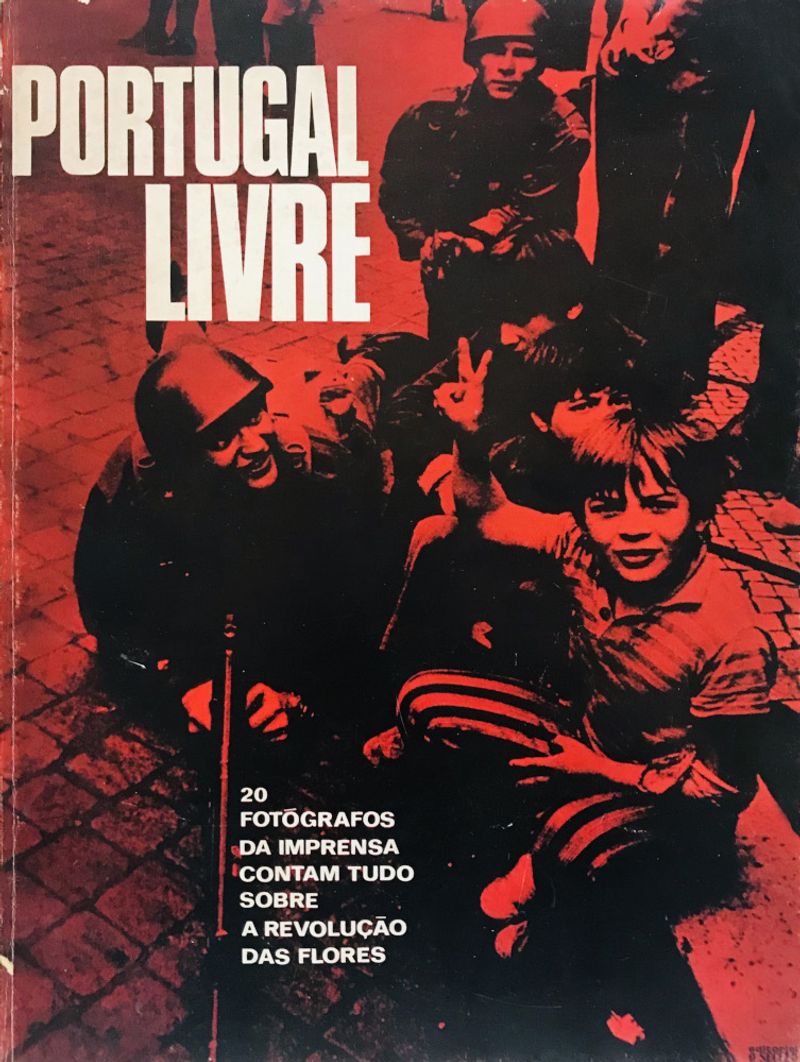

The Polish festival, running June 12-22, features a curated display of international protest photobooks selected from the Protestinphotobook collection.

A symbolic city of disobedience and dissent. A map of revolution and resistance, where the photographic urge to document meets a pressing need to disseminate. The selection of volumes on show represents historical evidence while allowing for an in-depth analysis of the medium. What do these books tell us, and what is the value of exhibiting them? How do design, photography, and publishing strategies come together to shape visual and political heritage? With the opening of In Protest We Trust set for 12 June in the post-industrial city of Lodz as part of Fotofestiwal 2025, we spoke with Luciano Zuccaccia, curator of Protestinphotobook, to understand his research, collecting ethics, and the exhibition's scope and curation.

What led you to create the Protestinphotobook platform and how do you keep growing it?

For over thirty years, I’ve been involved with photographic books, but it was since 2020 that I’ve chosen to focus my efforts on a thematic collection: protest books from around the world. After decades of research and discovery, I feel that this is the right moment to dedicate myself to a specific area, without getting lost within the infinite vastness of the photographic publishing landscape.

My daily work is now entirely oriented toward research of news, publications, and information related to this theme. With great pleasure, I note a growing interest in the collection from students, curators, historians, and international organizations, who see it as a point of reference for those wishing to explore or write about photographic books connected to protest movements, demands, and social change.

This way of collecting — more selective, mindful, thematic — goes beyond the pleasure of ownership. It is an approach that has allowed me to engage with powerful photographic, political, and sociological stories, which I now feel the duty to share. I am convinced that this direction, already taken by several collectors abroad, represents the future of photographic collecting: a future made of targeted choices, cultural research, and visual narratives that speak to the present. I wish for a debate among collectors, authors, publishers, curators, and scholars about this approach, to exchange views, reflect, and understand together where we are headed.

A fundamental element for the growth and continuation of the collection is the strategic use of the Internet and the support of a global network of trusted collaborators. The network allows me to discover often forgotten books, especially from the past, while collaborators locate rare and hard-to-find volumes locally: they are an irreplaceable resource for me.

Finally, I am happy to see that more and more publishers, photographers, and curators are recognizing the value of this project, offering their books to be included in the collection, both for online visibility and participation in exhibitions and events.

Starting from your collection, how did you see the photobook medium evolving?

The search for volumes published in the last century has allowed me to observe how the protest photobook has undergone a significant evolution in both narrative and visual structure. Over time, these publications have become enriched with color, diverse materials, and unexpected formats, sometimes incorporating artistic and graphic languages far removed from more traditional documentary photography.

The book has become a space for experimentation, where photographers no longer limit themselves to working solely with printers, but collaborate actively with graphic designers and book designers, creating complex and powerful narrative objects. It’s fascinating to come across a book that amplifies the visual message, stimulates new ideas, and becomes itself an integral part of the photographic project.

In the case of protest books, however, it’s not always possible to achieve the desired formal and distributional goals. By its very nature, the subject of protest is often marginalized, making it difficult to secure the funding needed for the production of a book, which is costly and targeted at a niche audience.

Yet photographers feel a deep need to communicate. So, even in the absence of institutional support, self-published works emerge, created through crowdfunding, printed as zines or newspapers. And these solutions work. Because beyond format or budget, what truly matters is printing on paper, leaving a physical trace, a tangible document. An act of resistance and memory that endures.

What do you think is the political impact of protest photography, and of photobooks more specifically?

In recent years, while observing photographic publications produced in various parts of the world, I’ve noticed how protest photography is deeply connected to local contexts and the social movements that take shape within them. Differentiating by geographic area helps to better understand the cultural and political dynamics that drive editorial production.

In Europe, for example, I was struck by the rich output of books linked to environmental protests in Germany. A scene likely encouraged by the historical commitment of the German Green Party to these issues. These books reflect widespread, deeply rooted activism, conveyed through mature visual languages and carefully curated editorial projects.

In South America, particularly in Chile, many photographers have documented the civil and social rights demonstrations that have taken place in the capital, Santiago, for years. These are often independent, grassroots publications that powerfully and urgently give voice to young people and marginalized communities.

Even in countries like Slovenia and Poland, books have been created that explore the socio-political unrest especially felt by the younger generations. These works give form and visibility to a widespread unease that is often ignored by mainstream media.

Activism and resistance have always been strategies to give voice to both public and personal dissent. Now more than ever, I don't know what the actual political impact of protest photography is, but I strongly feel that its transposition into printed form is essential. In an era dominated by fleeting and digital communications, the photobook stands as a concrete testimony, resistant to time and censorship.

Often, the photographers who document protests are themselves part of the movements. They are not mere observers: they are engaged, they participate, they believe in the message. And even knowing that this kind of photography doesn’t guarantee economic returns, they still choose to create books, zines, newspapers. Because what truly matters is leaving a trace.

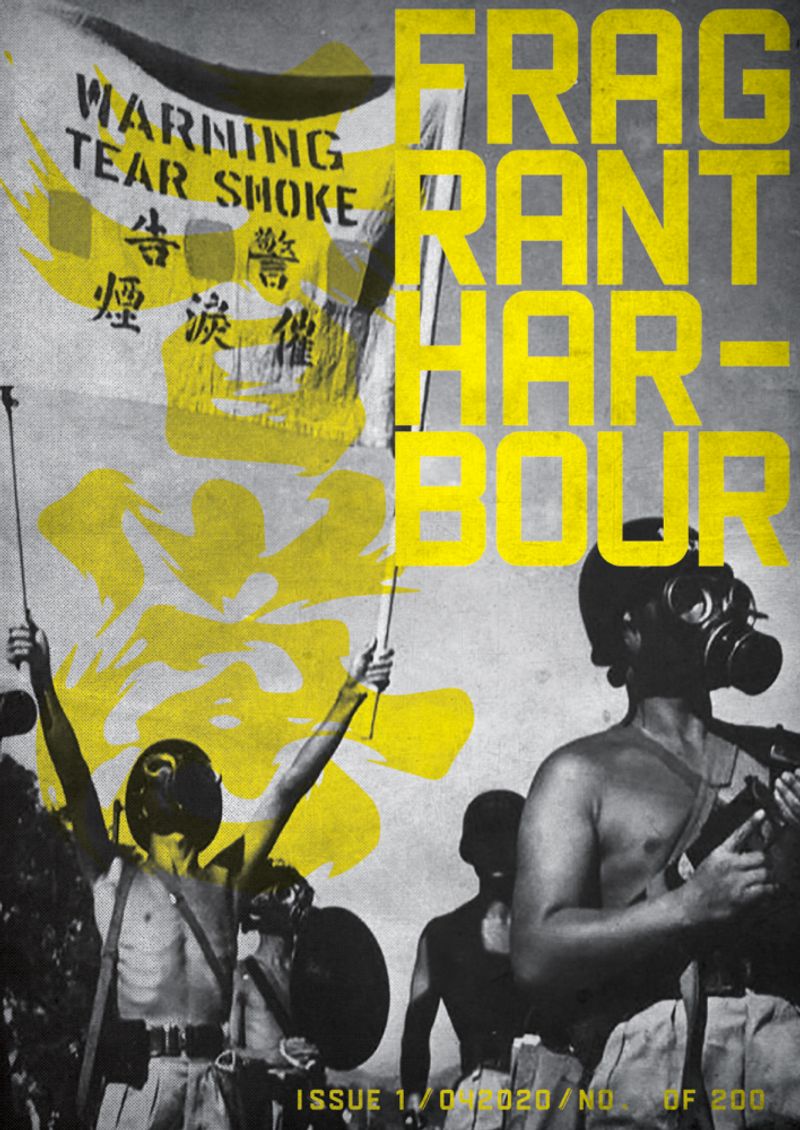

A particularly emblematic example comes from Hong Kong, where during the Umbrella Movement demonstrations, a book called Fragrant Harbour was created as an "on-demand" edition, distributed via QR code to circumvent restrictions on printing and shipping. It will also be featured in the exhibition: a new frontier in protest publishing that combines creativity, resistance, and technology.

The exhibition will be structured along the topics of “People’s Rights, Women’s Claims, Student Protest, Coup d’État, Revolutions, Independence and Environment”. How did you define these threads, and why did you decide to have them as a guiding principle?

The topics related to protests around the world are vast and varied, extending far beyond those addressed in this selection. We could even imagine sub-categories, such as that of anti-establishment movements, which encompass multiple nuances of dissent and resistance. However, I believe that the selection in this exhibition represents a solid starting point, offering a meaningful overview of major global protest movements.

Today, the collection consists of around 900 books: presenting 60 volumes in this exhibition inevitably requires a selection process. Nonetheless, I can confidently say that the chosen books are among the most representative of global protest movements. We have aimed to provide a historical perspective, spanning from the post-war period to the present day, in order to offer a long-term reading of social and political change through photography.

Every day I discover new books and stories that enrich the collection, some linked to local protests, minor events, or even censored movements. These discoveries continue to show me how alive and dynamic this collection is, and how the documentation of protests remains a constantly evolving practice.

It’s not just about famous events, but also about quiet stories, daily resistance, and marginalized voices that find space on paper. I am certain that in the future we will explore other themes, gather new volumes, and delve into new topics, in order to continue nourishing a never-ending pursuit.

What can one expect as they navigate through the exhibition? Can you tell us more about the idea of conceiving it as a symbolic city?

The exhibition stems from an idea that sees the city as a symbol of protest, a place where dissent manifests in all its forms, from the center to the outskirts. Protests know no borders and spread through urban nodes, creating a network of intertwined stories that reflect the complexity of our world.

For this reason, I chose to present the books in the collection using an urban metaphor, arranged like stations on a symbolic subway map, which allows for exploration and changes in direction, much like the movements of protest themselves. The invitation is to view the books not merely as static objects, but as fluid and interconnected elements, encouraging visitors to draw comparisons between them, in a play of references across forms, contents, and contexts.

Each book, though belonging to a specific geography and historical period, is a piece of a complex network that spans across distant times and places, carrying testimonies and visions that are often not seen in relation to one another. These books have never ‘spoken’ to each other: they come from distant continents, different editorial traditions, and have never before been placed side by side.

The exhibition aims to create an opportunity for these unexpected comparisons to emerge, to explore typography, design, and layout differences, particularly in books from the last century, when typography and design were still closely tied to manual craftsmanship and local traditions.

Along this journey, visitors are invited to travel through the diversity of visual languages and expressive methods, discovering how each protest book is a unique testimony, but also part of a global narrative unfolding in parallel and intersecting paths.

What are the challenges and the most interesting aspects in translating a book collection into the exhibition format?

Proposing an exhibition of photographic books is always a stimulating challenge, a delicate balance between the desire to share rare works and the need to protect pieces that are often fragile. Books, especially historical and delicate ones, are tangible testimonies of stories that cannot be replaced, yet exhibiting them requires careful and respectful handling. For this reason, some books will be protected under plexiglass to preserve their integrity, while others, being less vulnerable, will be available for the public to browse.

Fortunately, the audience in Łódź is well-versed and appreciates the care with which the exhibited objects are handled, which allows us to create an experience of direct engagement with the books. This is not only an invitation to observe, but also to touch and explore the texts, to discover firsthand the stories and forms that make up the collection.

The act of leafing through a protest book is one of deep engagement, it allows one to sense the materiality of the content and connect with the visual and emotional message each volume conveys. It will be interesting to see how the public responds, what they discover as they browse the books, and how the comparisons between different editorial and graphic traditions might influence their perspectives.

Each book is a window into a historical and social context, and the dialogue with visitors will offer new interpretive keys, enriching the meaning of the collection itself. For me, this is the first time I’ve exhibited so many books together, and this exhibition represents a unique opportunity to engage directly with the public.

It’s an experience that will allow me to refine my approach and learn from their point of view. Every interaction, every observation, and every question will be a valuable insight for future challenges and for the continued growth of this ever-evolving collection as it engages with the world.

Looking at all the books you chose, did you find any unexpected links between them, or specific stories you’d like to highlight?

Looking at the selection of collected books, I realized that their design represents an additional layer of curation and a possible interpretation in itself. Analyzing the graphic design of the books opened up new connections and references for me. The photobook is not just a container of images; it is a communicative object that conveys a message through its form and structure.

Throughout my experience, I have always viewed books from multiple perspectives, and design has been a crucial key in understanding how visual languages have evolved. From the photojournalists of the 1970s, with their documentary approach, we’ve moved toward increasingly experimental uses of imagery, ranging from protest photography to visual art.

I can cite several examples that reflect this evolution. A classic is Il '77 (1978) by Tano D’Amico, a work that preserves the memory of an era and a movement, but also The Revolution in Images (1979), a visual testimony by Iranian photographers Parviz Zouman, Hashem Faroutan, and Seifollah Samadian, who documented the socio-political transformation in their country, and VOM MURI SI VOM FI LIBERI – ALBUM REVOLUTIE (1990), which chronicles the Romanian revolution.

Another significant example is 1968 destinos 2008 – Passeata dos 100 mil (2007) by Evandro Teixeira, which reflects on Brazil’s historical memory, and Strajk / Strike (2021) by Rafał Milach, documenting the protests in Poland.

However, among all the stories I would like to highlight, that of Nona Faustine is especially important to me. Her book White Shoes (on display) is a powerful act of protest against slavery and the subjugation of Black people, a topic that, unfortunately, continues to be too often overlooked.

During our last meeting in Rome, I had the privilege of speaking with Nona about her commitment to this cause, and how the book was, for her, the most powerful and appropriate medium to address such a difficult subject. Her passion and determination in telling these stories and in bringing uncomfortable truths to light is something that will stay with me forever. Her work is a testament to the power of the book as a tool for resistance and change.

--------------

All images © Protestinphotobook

--------------

Now at its 24th edition, Fotofestiwal is one of the most important events related to photography in Poland. Taking place on 12-22 June in the post-industrial city of Łódź, the festival comprises a premiere of Yorgos Lanthimos’ exhibition, projects that uncover American propaganda and fiction, many exhibitions in the open and urban space and the first photobook exhibition fully dedicated to children. Learn more on https://fotofestiwal.com/2025/en/