Fleeing Argentina During the Military Dictatorship

-

Published14 Apr 2021

-

Author

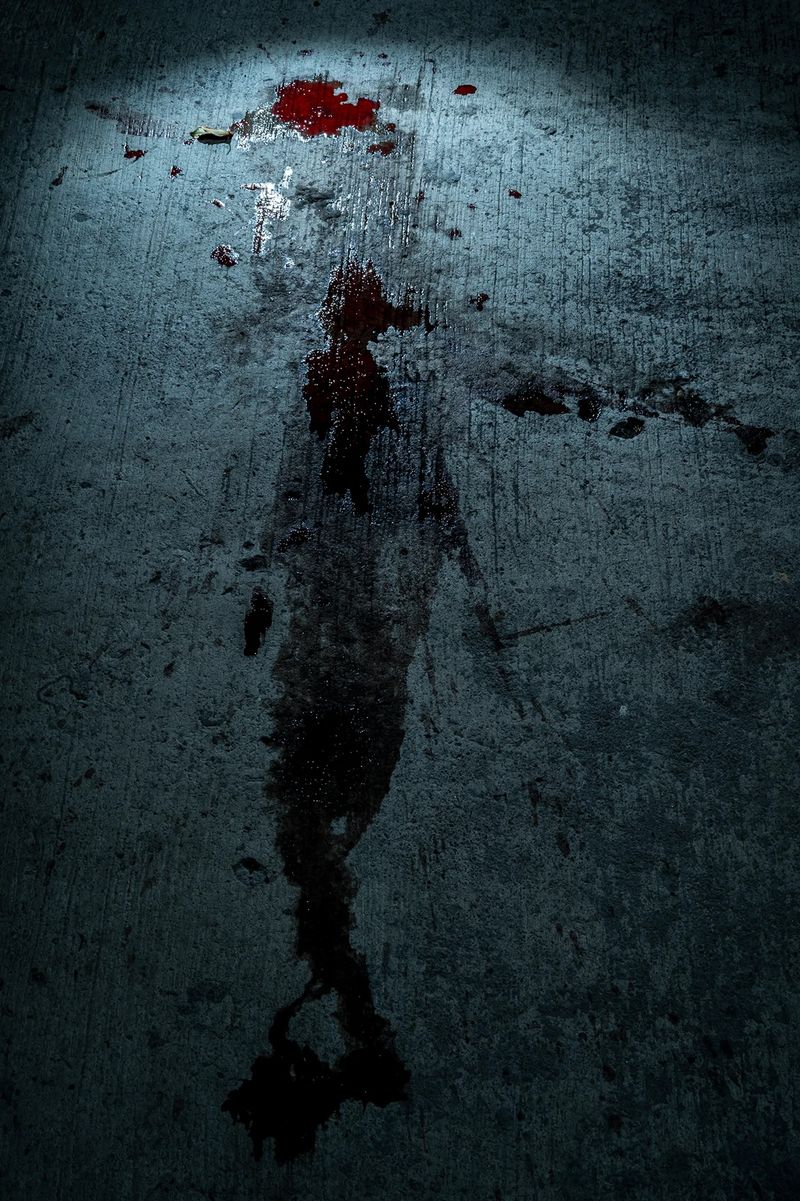

Mexican photographer Valeria Arendar re-enacts her mother’s escape from Argentina during the military repression in the 1970s. Driven by her mother’s recollections and collective memories, Valeria creates haunting images that portray the distress of fearing for one’s life and safety.

Mexican photographer Valeria Arendar re-enacts her mother’s escape from Argentina during the military repression in the 1970s. Driven by her mother’s recollections and collective memories, Valeria creates haunting images that portray the distress of fearing for one’s life and safety.

Valeria Arendar is the daughter of an Argentine political refugee, María. Valeria was born and raised in Mexico yet grew up hearing tales of her mother’s bravery during the military dictatorship in the South American country that later led her mother to migrate to Mexico. In a collective effort to tell her mother’s story and of the many disappeared-missing in Argentina, Valeria began to investigate her mother’s experience to visually represent her memories of torture, pain, and a sense of void.

Valeria, could you tell us more about the title you have chosen for your series: Two Times Mary. How does it connect to the project?

My mother's name is María Patricia. She was named María after her grandmother, however, since she was little, everyone knows her as Patricia. I think it’s also important to mention that my mother's life of activism dates back to when she was 15 years old. During the 1970s, she mainly did community work. That is understood as a political organisation with people in certain spaces.

When the repression and political persecution began in Argentina, around 1974, she decided to use another name to protect herself. Maria was the name she chose.

Carlos Acosta (detained-disappeared on July 20th, 1976), a companion and friend through my mother's militancy, was the one who endured 24 hours of brutal torture by the military. During these interrogations, the militants asked the names of the comrades with whom they worked politically. And the name that Carlos gave, under torture to the military, was precisely María, my mother. Hence, when the military raided the house of my maternal grandparents on 21 July 1976, they were looking for María. And in that sense, I remember very clearly a phrase mentioned by a witness I interviewed about that night when a soldier told my grandfather: “María, your daughter, has been having unhealthy relationships. If she had been here we would have taken her with us”.

Later in Mexico, Mom used other names such as ‘Patricia Rojas’ fearing the constant political persecution in Latin America. I believe that the title Two Times Mary is a re-encounter of two lives and that of a survivor of the last civic-military dictatorship that Argentina lived through from 1976 to 1983. It is like a way of telling and narrating a story from disorder and from other types of power that manifests themselves in a political act whose starting point is the search for a deep love for others and a political commitment to life.

What's been like to visually represent pain? How have you worked on recreating the memory photographically?

Representing pain visually implies working with subaltern memories where archives are constructed by opening ourselves. I understand by subaltern memories those that recover, save and process documents in various media: memories, smells, visions, corporal information and countless documents that speak of resistance in all its forms.

With that being said, it is necessary to problematise the transition between the image and the word. That is to say, that the lived experience is deepened in a conscious reactivation of social and individual memories through a praxis based on orality, writing and the construction of images. Something like making a more complex memory of the public through personal memories.

These actions have allowed me to understand the body as a primal territory. But visually representing pain is also a kind of expression that is typical or characteristic of the past and yet it occurs today. In other words, to speak of a past that arises and bursts into the present time.

Working on the recreation of memory allows me to settle in the gesture and action of disobedience in the face of what can be remembered and, therefore, in the face of what can be said and thought about everything that the construction and recovery of identities implies. These are affections and stories that the civic-military dictatorship in Argentina sought to disappear, forget, erase and deconstruct.

It is very difficult to represent in a single image the pain of absence, the loss of a political project and a country, and the separation of families. What I try to do is stage what I think from a transgressive procedure where I explore my own history through a Sociology of Absences, a concept proposed by Boaventura de Sousa Santos in Epistemologias del Sur.

Have all your images been taken in Mexico?

At the end of 2019, I travelled to Buenos Aires, Argentina, together with my mother to visit family. During our stay, we went to the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA) for a meeting with experts from the Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF) for my mother to testify as a witness regarding what she remembers about her friend, Carlos Acosta, who was detained-disappeared on the 20th of July 1976, and also to testify about her partner at the time, Gerardo Álvarez, who was also detained-disappeared on December 21st, 1977. (PRESENT NOW, AND ALWAYS!)

During the civic-military dictatorship, the ESMA functioned as a clandestine centre for detention, torture, rape, dehumanisation and extermination. I think that, based on impulse, I took some pictures during those meetings. Those photos and that experience that I later understood as a kind of identity anguish was for me what triggered the beginning of this project.

Back in Mexico, once I began to shape an investigation between my mother’s letters and diaries from that time and the few photos that exists of her at the time as well as interviews with specific people, I made the decision to take the photographs in Morelos, Mexico. I consider it important to take the photographs in Morelos because it is a way of narrating my own imagery of the dictatorship and forced disappearance from a territory that I have known since I was a young child.

You have produced photographs and a multimedia piece for this series, can you tell us more about the difference of each medium?

Sometimes I think that photographic projects take a lot from the methodology of cinema. In both; the photographic project and in the multimedia piece I try to treat the elements of "the real" in the sense of an experimental arrangement. That is, each staging should dialectically criticize each other. Precisely the question of assembly (the montage, the edit) as one more instrument proposes to dismantle the existing order and provoke a new arrangement of things. That is particularly interesting to me.

Retaking Didi-Huberman -in an interview conducted by Amador Fernández-Savater - through montage, two images that were not related assume a different position and thus a critical gaze is fostered. In my experience then, I could say that the difference lies within the viewers and the aesthetic function to which all phenomena can be linked. However, in both cases, there is a point at which the image indicates something that is not only appearance because "they touch the real, without being the real."

What's the future plan for this project?

Currently I continue researching and trying to make tangible this social imagery with which I grew up. What I would like to do one day is to build a photobook for the project and understand it as an autonomous work because I think it is important to analyse the consequences of remembering and how this impacts our here and now.

45 years after the military, civic and ecclesiastical coup in Argentina, all that we have left is memory and it is what we have to revitalise. Especially due to the fact that the Abuelas y Madres de Plaza de Mayo will not be able to physically accompany this fight forever. Faced with this anguish of the possibility of forgetting, being able to recall and remember something from the past is what sustains our identity. For painful memories always survive that wait for the right moment to be told.

And this leads me to bring to this interview; "they were taken alive, we want them alive." But life is not exclusively the bodily extension of a biological being. Life is the political commitment that at its founding level is always trans-generational.

All photos © Valeria Arendar from the series Two Times Mary

-------------

Two Times Mary is the recipient of Intersection - PHmuseum Exhibition Prize Vol.1. Valeria will exhibit her work at Fonderia 20.9, a photographic gallery in Verona, Italy, this year.

-------------

Valeria Arendar is an Argentine-Mexican photographer based in Mexico. She graduated from the Seminario de Producción Fotográfica del Centro de la Imagen (2019-2020) under the tutelage of Nirvana Paz and Óscar Farfán and this year she was a finalist at POYLatam, where she received an Honorable Mention in Nuestra Mirada category. You can follow her on Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

-------------

This article is part of In Focus: Latin American Female Photographers, a monthly series curated by Verónica Sanchis Bencomo focusing on the works of female visual storytellers working and living in Latin America.