Through the Border, Through Their Eyes: Lisa Elmaleh on the Humanity of Migration

-

Published4 Mar 2025

-

Author

- Topics Contemporary Issues, Documentary, Social Issues

In her series Tierra Prometida/Promised Land, photographer Lisa Elmaleh exposes the deadly reality of the border wall while capturing the resilience and humanity of migrants, bringing to light personal stories too often overlooked.

Lisa Elmaleh first arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2020, near the end of the Trump’s first presidency. Construction on the wall was accelerating then—companies were offered bonuses for every mile completed. Yet beyond the region, few knew what was happening.

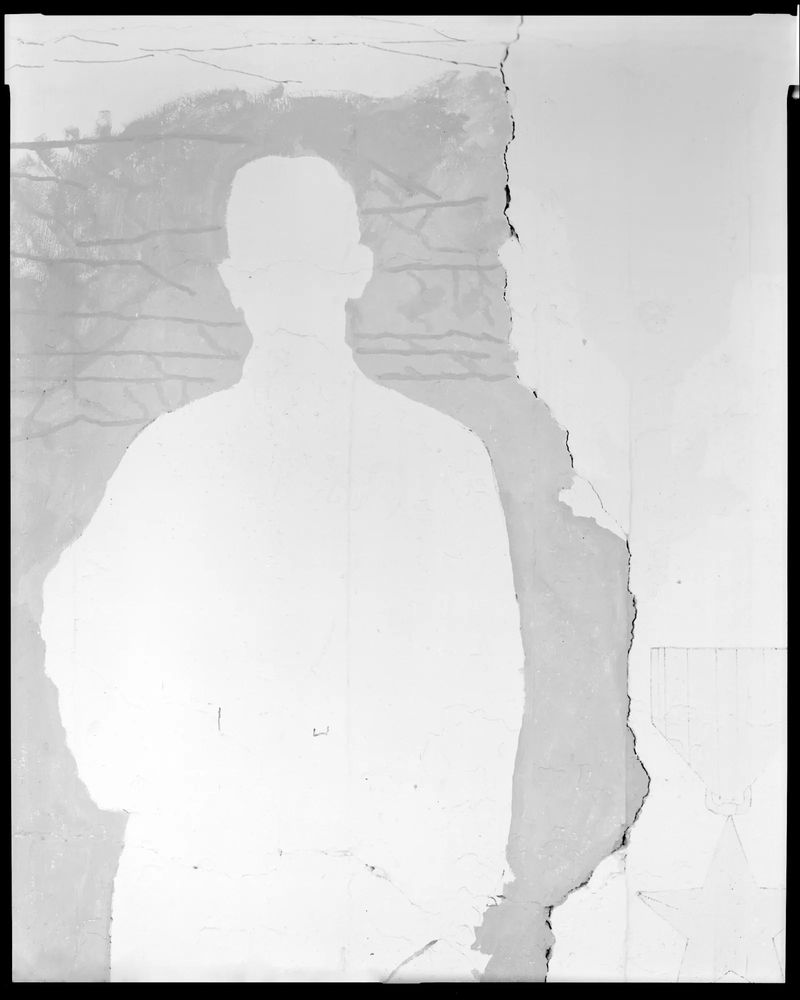

As the wall tore through the landscape at breakneck speed, Elmaleh traveled there to see it firsthand, to photograph it. She was struck by its sheer scale—30 feet tall, towering over everything. As she researched its height, she discovered a chilling fact: it was also designed to cause harm. A fall from that height would almost certainly result in serious injury, if not death. The realization unsettled her. This wasn’t just a barrier—it was also a weapon. And with that realization came a haunting question: “Who are the people that we're trying to keep out?”

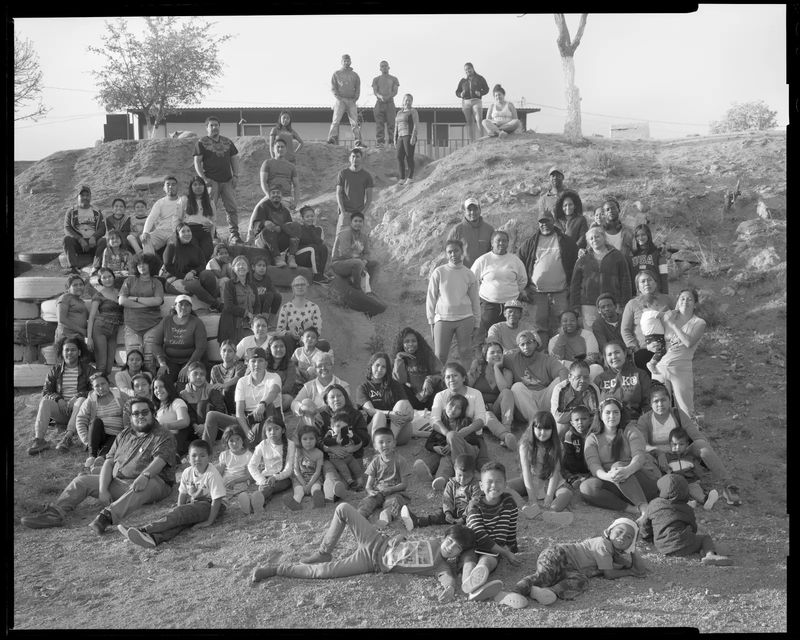

That question led her to stay and to begin her body of work, Tierra Prometida/Promised Land. Elmaleh began volunteering with humanitarian aid groups, living with Kino Border Initiative and Casa de la Misericordia, both migrant shelters in Nogales, Sonora, a city on the Mexican border—immersing herself in the community. Her role was not just as a photographer, but first and foremost as a volunteer, a friend, an ally. Only then—as a visual witness.

“Once I started working on this project, I started getting to know people migrating, and hearing their stories,” Elmaleh says. “I realized that our news lacked the humanity to talk about people in a way that was dignified.”

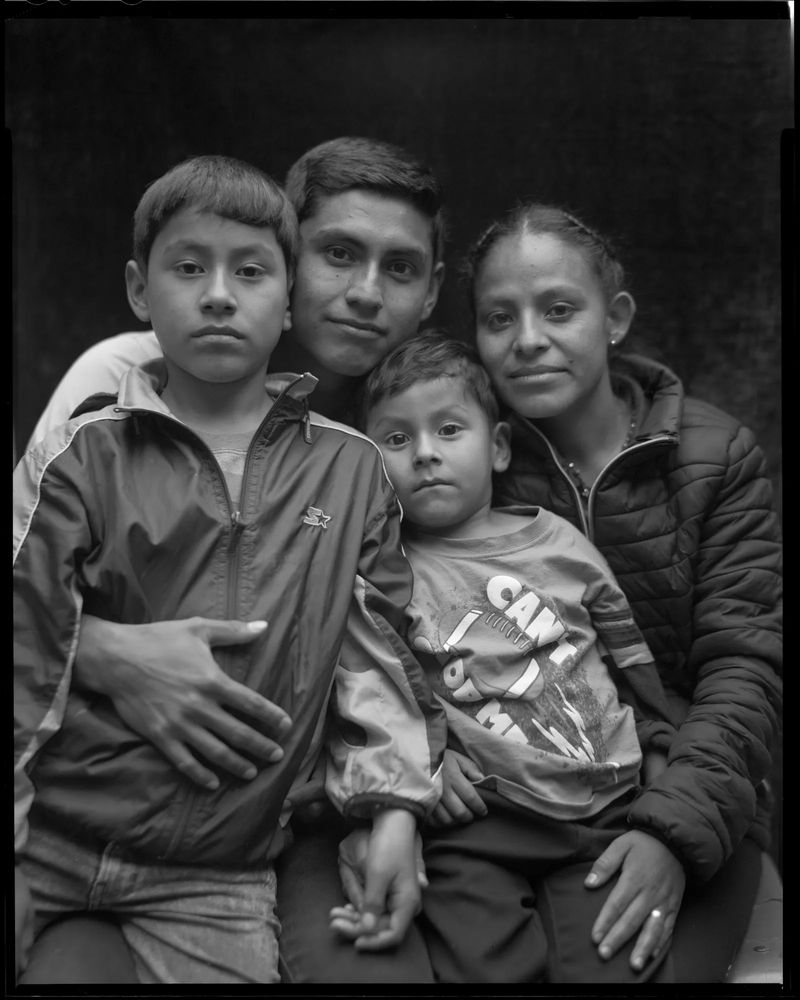

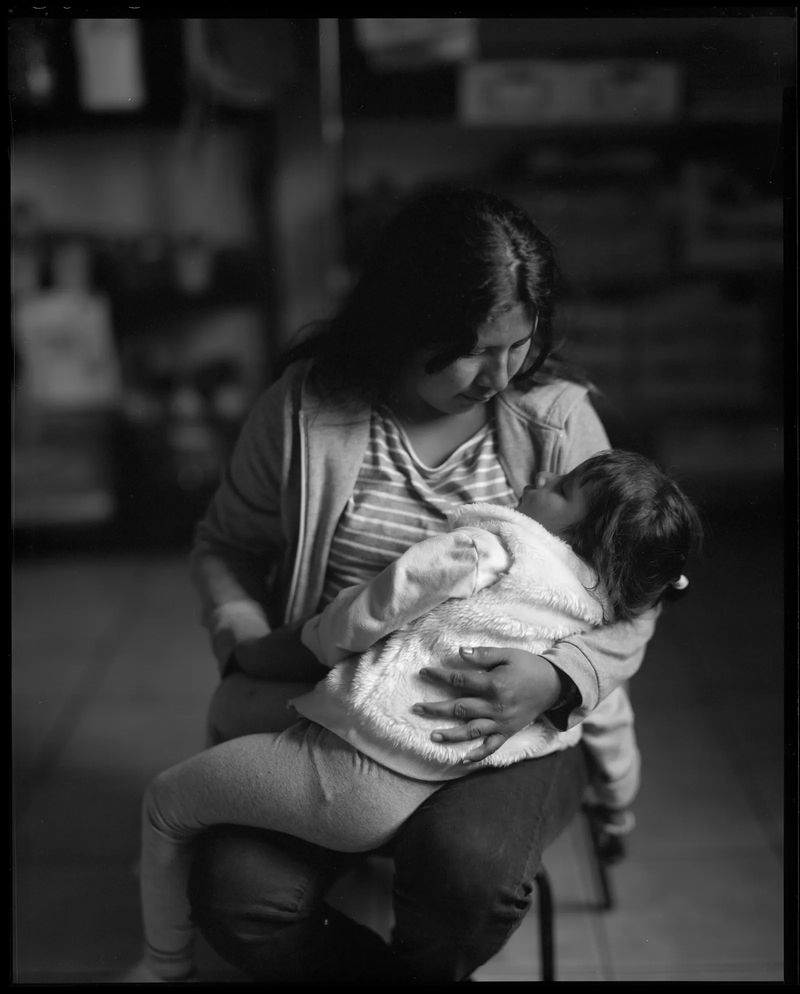

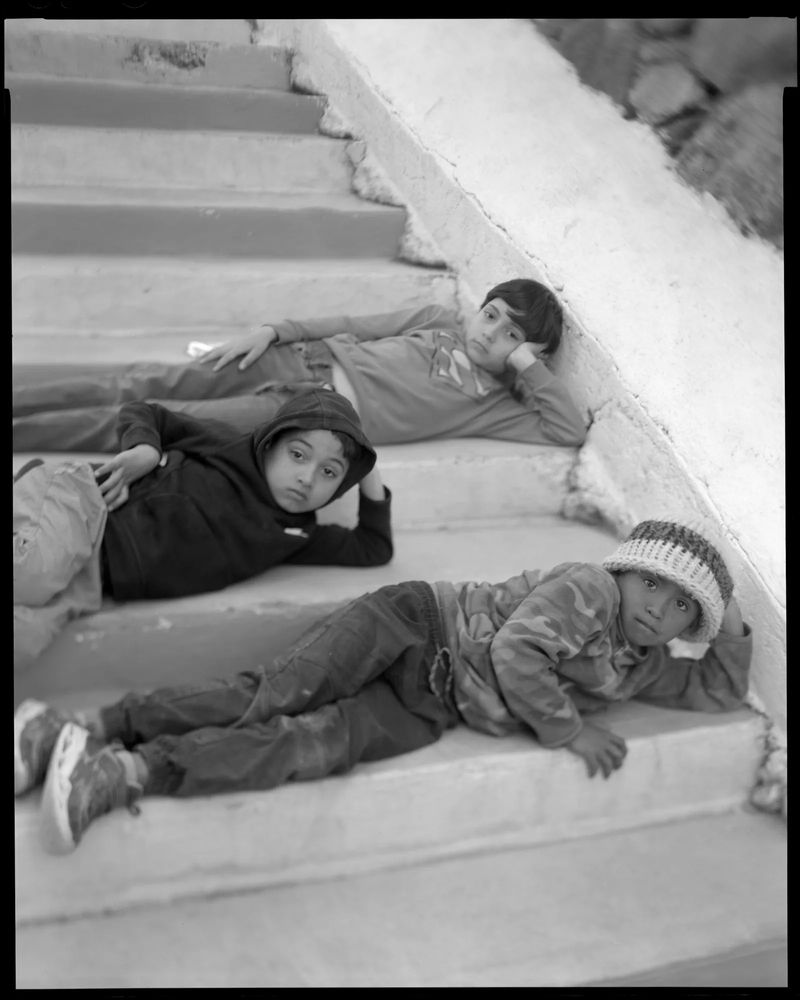

Elmaleh met families in the midst of migration—many of them single mothers with children, entire families traveling together. The more she listened, the more she saw how news coverage stripped migrants of dignity, reducing them to statistics rather than individuals with lives, struggles, and aspirations. That realization fueled her work. She wanted to document their stories with deep respect, countering the detached narratives that failed to see them as human.

“When I'm making a picture of a person who's sitting in front of my camera, it's not just about taking the picture and we're done,” she explains. “It’s about being here, hearing the story, understanding in a deeper and more respectful way, and trying to communicate that to the rest of the world.”

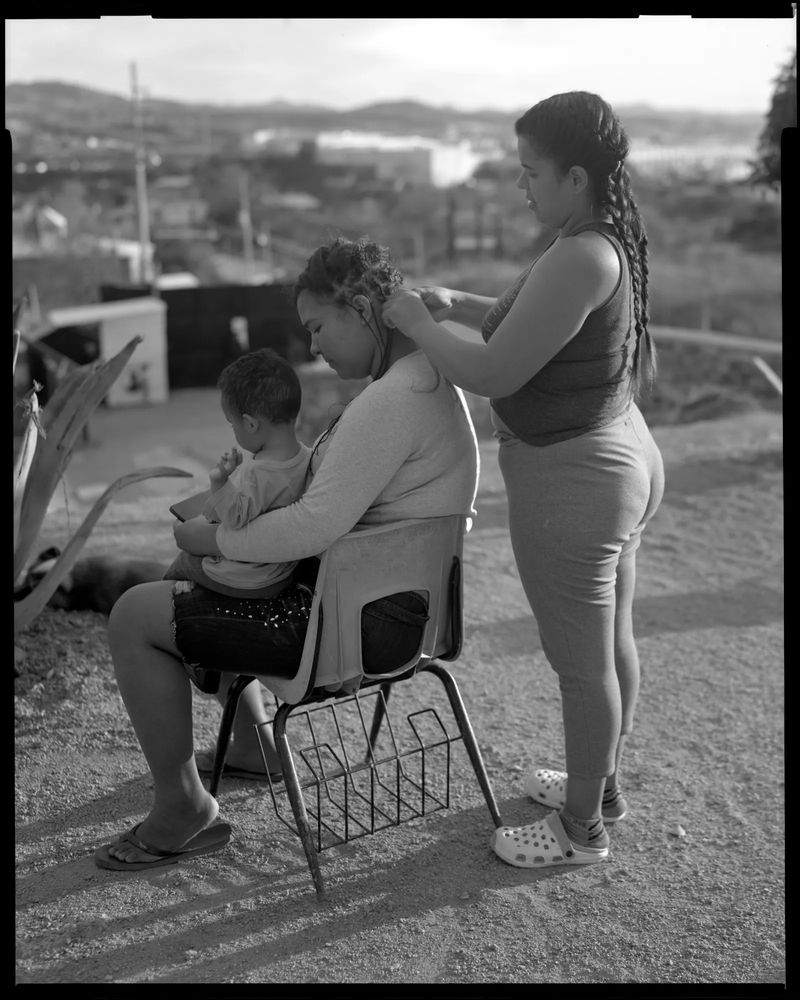

Elmaleh works with a large-format 8x10 camera—its size and complexity demanding patience, collaboration, and consent. At the shelter, it becomes part of a shared experience. Children, especially, are drawn to it. Because the camera is at her eye level, they’re often too small to see through it—so she lifts them up, letting them peer inside and watch the world flip upside down. And when everything feels right, she takes the picture. Nothing is forced. Each portrait is an act of choice.

“I want to photograph people from my own perspective, one of extreme respect and empathy. The things that people have experienced, trying to migrate to the U.S., are things that so many people would never be able to live through.”

After the last presidential election, the mood shifted. First came confusion, then deep anxiety. Then, a heavy stillness. For many, returning home isn’t an option. And the wait for asylum—months, a year—can feel impossible. But the shelter often offers more than just a place to stay. It gives families a chance to maintain some sense of normalcy, to live rather than just wait.

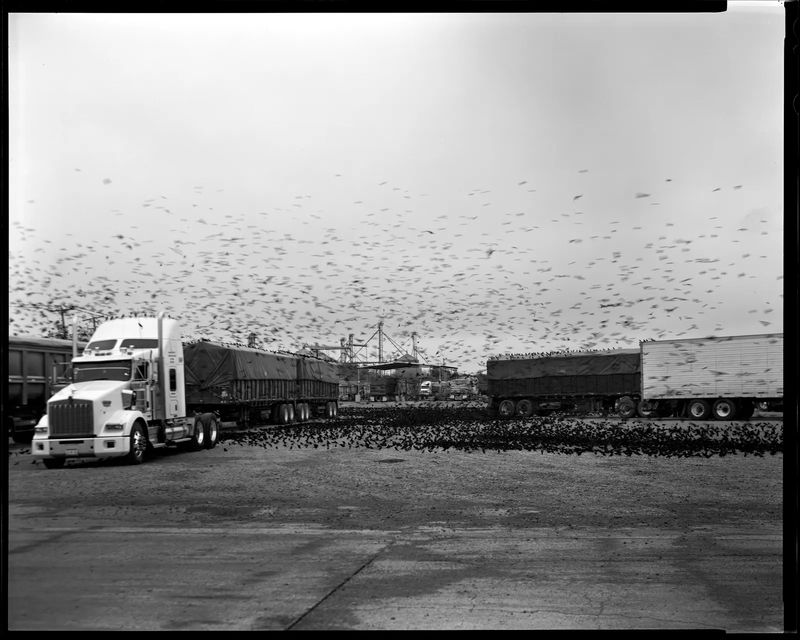

One of her images captures the migration of red-winged blackbirds, a metaphor for movement and borders. Birds cross freely, she notes, unaware of the imaginary lines drawn by humans. The border is not a natural divide—it’s imposed. But who gets to dictate that boundary, and why? Migration is a natural process, yet some move freely, while others are denied that right. For some, migration is a choice—even a privilege. For others, it is a necessity born of desperation. No matter the circumstance, Elmaleh respects the resilience and sacrifice that defines their journey.

Last year, Elmaleh volunteered with groups such as the Tucson Samaritans and Humane Borders, at times offering water and food to the hundreds of migrants who walk for miles along the wall before turning themselves in to Border Patrol to request asylum. Only after everyone’s immediate needs are met does she take out her camera, carefully setting it up and explaining why she is photographing.

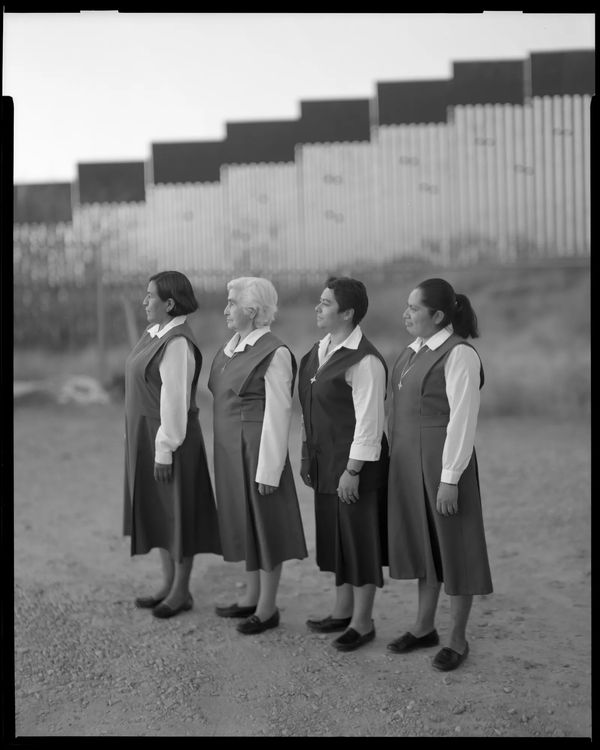

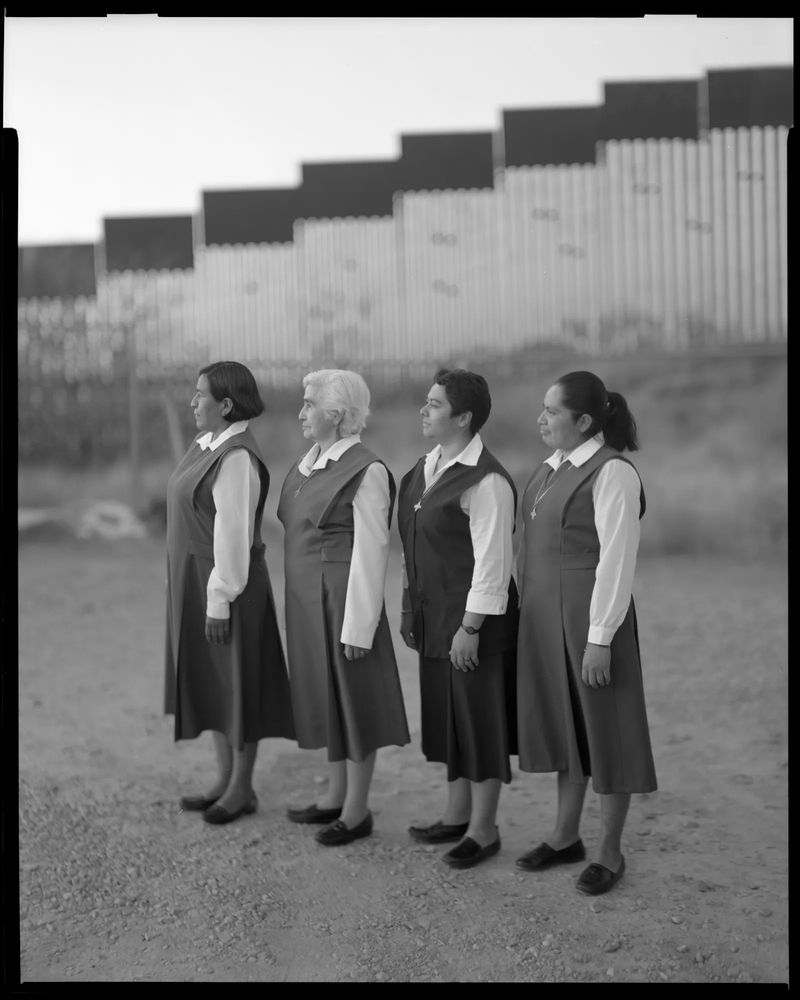

In one of her photographs, four nuns stand by the border wall. They are members of the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist, who began their work in Nogales decades ago. What started as handing out burritos from the back of a van has grown into a full-fledged organization. Over the years, they secured a space to cook meals for individuals in need, expanding their efforts into a larger shelter and support network.

Elmaleh remembers a quiet moment at the end of a long day, sitting down for dinner with the sisters at their home. As they talked, she asked if she could photograph them in front of the border wall. They stepped outside, standing before the very barrier that defines so much of their mission. They stood strong, aligned as the border wall behind them—heartened by the compassion they present and serve.

“Participating in this deepens my understanding of what’s happening in all aspects of migration.”

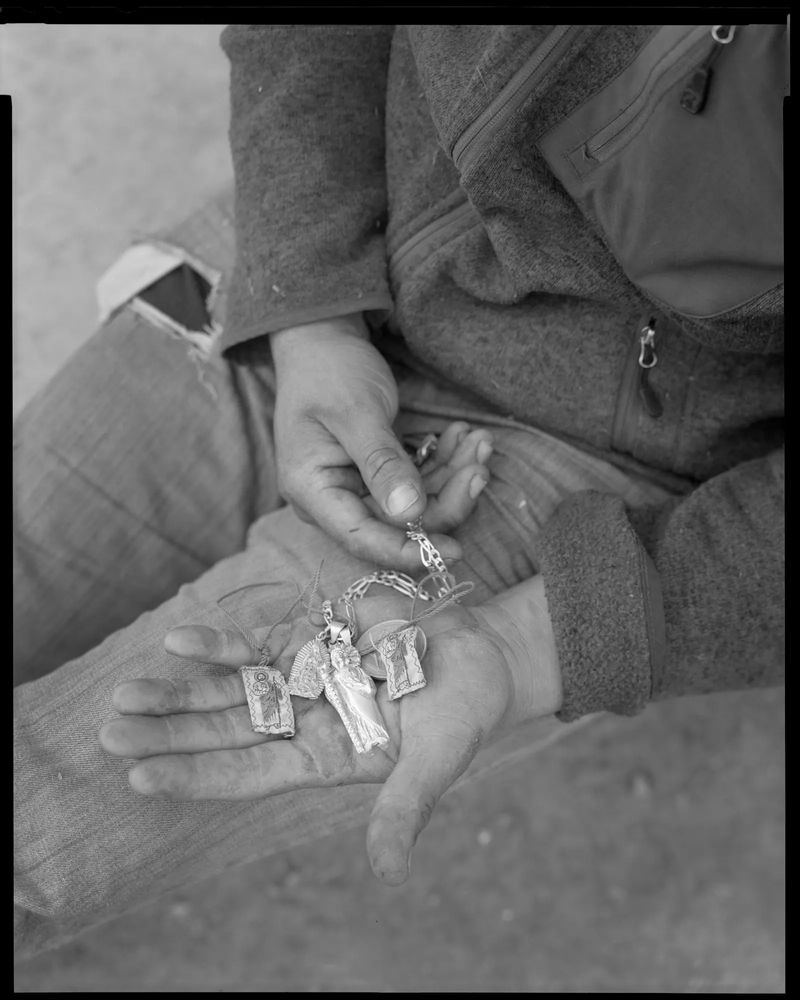

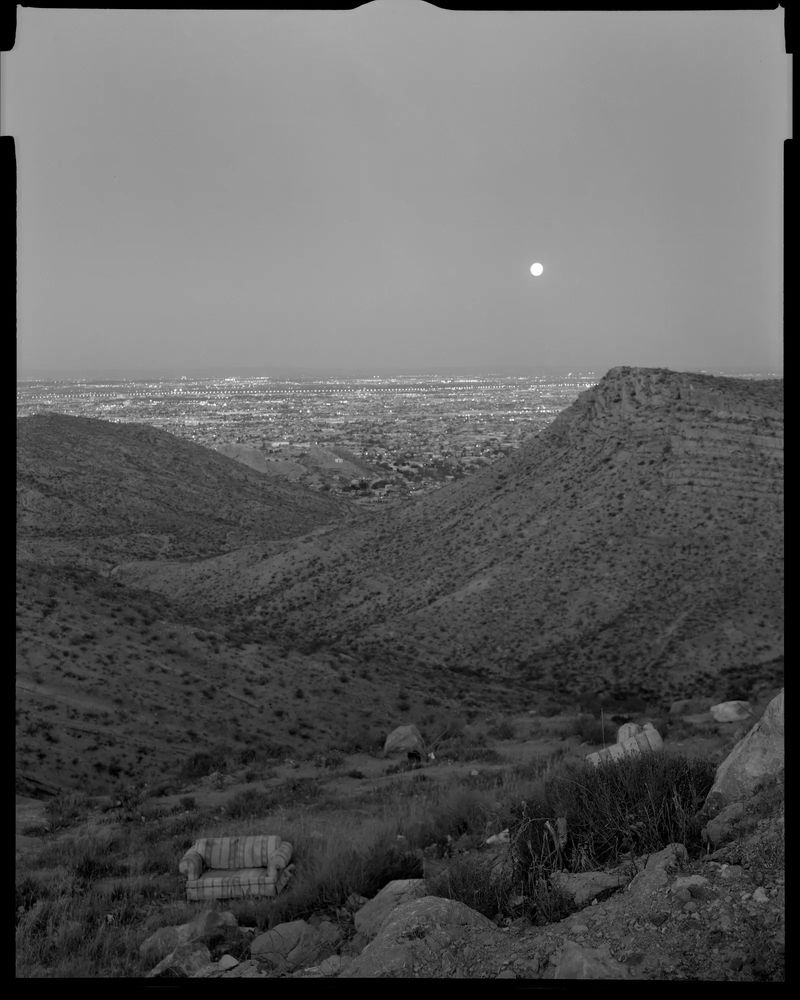

And in her photographs, she reflects all the humanity she encounters on her journey. A woman gazes hopeful at the sky, her face bathed in the soft light streaming from an opening above; the warmth of a family’s embrace or the playful energy of children shine through. In one image, women braid each other’s hair, while in another, a man stands distantly before the wall, his frame dwarfed by the vast structure built to keep him out. There are cameras, barbed wire, and pendants of good luck. There’s an abandoned sofa beneath a moonrise in the middle of the desert, El Paso on the horizon—it makes one think of those who attempted the crossing in vain. Elmaleh has joined search and rescue missions with the group Águilas del Desierto, which looks for people who have gone missing in the Sonoran desert of the United States. Border Patrol does not normally conduct searches for those lost in the desert.

Though she doesn't document every part of this work, being involved gives her a deeper awareness of the migration crisis—insight that informs not just her photography, but her entire perspective on the issue.

“I believe in humanity. I see what people have lived through here and what they've survived,” Elmaleh says. “And they can still laugh, they can still love... If anything, we should be looking up to the people the media tries to make us look down upon.”

--------------

All photos © Lisa Elmaleh, from the series Tierra Prometida/Promised Land.

--------------

Lisa Elmaleh is an American visual artist, educator, and documentarian specialized in large-format work in tintype, glass negatives, and celluloid film. Since late 2020, she has been working on Promised Land/Tierra Prometida, a project documenting the U.S.-Mexico border and the impact of U.S. policies on lives on both sides. Find her work on PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram and Twitter.