Billy H.C. Kwok Documents a Mother's Search for Her Missing Son

-

Published6 Aug 2025

-

Author

Kwok’s photographs reveal the emotional moments behind and after a disappearance that the media never fully told—highlighting hope, loss, and resilience.

A boy vanished at the border.

That thin shifting line between Hong Kong and mainland China—drawn across gentle hills, a river, and morning fog—hides as much as it reveals. When the mist lifts at dawn, it reveals the land—but like the land it once hid, people can vanish too.

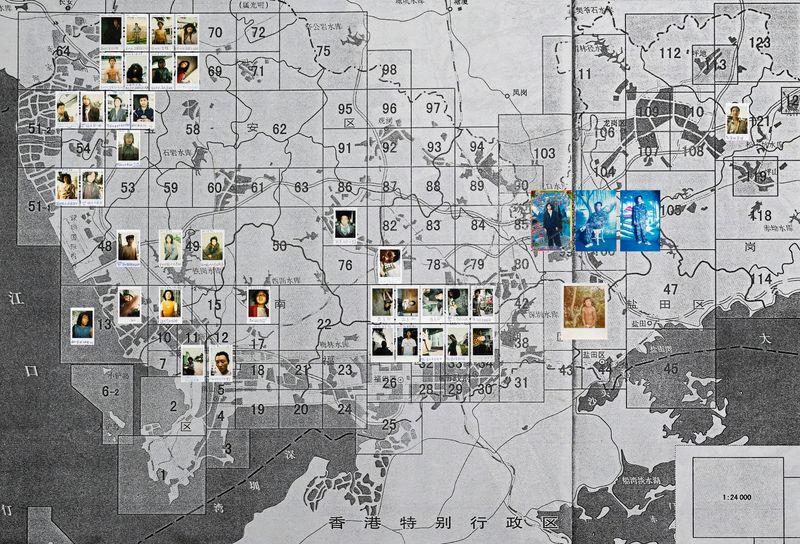

Billy H.C. Kwok was still a boy when he first heard the story. It was a major news event in Hong Kong: a young man had gone missing somewhere near the border. His mother, Yu Lai Wai-ling, began an intense, years-long search—traveling back and forth across the region, placing ads in newspapers, appearing on television, following every lead she could find. Her efforts made her a public figure, known for her pain and persistence. Strangers approached her with tips—some sincere, others deceitful.

Now, almost twenty years later, Kwok began to investigate: How could a young man vanish in that strip of land? “It raised so many questions as I started the research,” Kwok says. For So Many Years When I Close My Eyes is his story about a mother, her love for a missing son, and the land that separated them.

Soon enough into the work, Kwok sensed that the story reported so far wasn’t complete. “This is a very important story,” he says, “which is underexposed, so I want to take it to more exposure to people in Hong Kong.”

After spending several years in Taiwan, Kwok had worked on a project exploring the relationship between national archives and personal histories. So when he returned to Hong Kong, he adopted that same approach—blending it with his work as a photographer. “It all came together at that time,” he says. “I’m using two practices to tell one story.” But this story was too complex for pictures alone.

As a media photographer, he was always taking pictures, he explains. “But sometimes, an image alone can’t carry everything you want to say.” That realization led him to expand his storytelling to include not just his own photos, but also documents, letters, images from others, and testimonies drawn from court records and government archives. “I realized that photographs weren’t enough. I needed other materials—other voices.”

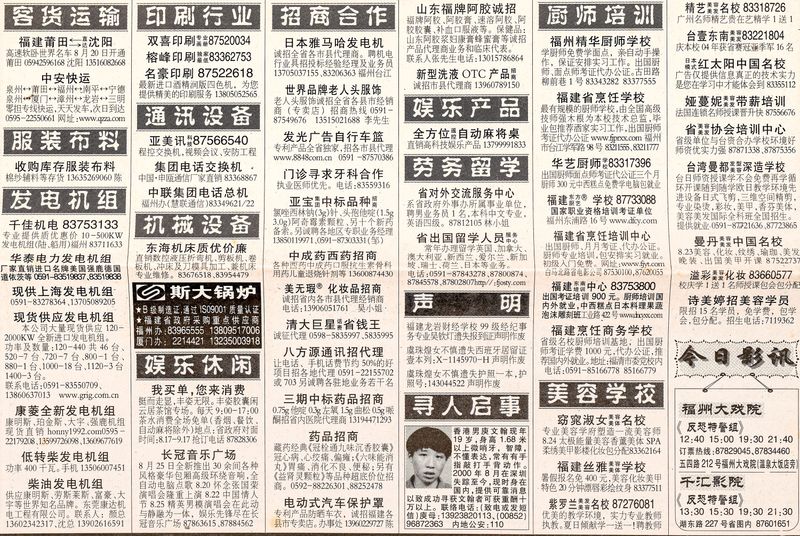

Kwok’s relationship with the mother unfolded differently from his usual work. In the beginning, he didn’t photograph. He would only consider photographing something if it revealed new significance or added important elements to the story. But in For So Many Years When I Close My Eyes, the images he created were only one layer. The heart of the work lies in the mother’s own archive: fragments of a life interrupted, collected over the years.

As they continued to talk, it became clear that the media’s framing had shaped much of the narrative, leaving a gap between the family’s private truth and the public version of events. Kwok’s work pushes back against this simplification, holding space for both the personal and the public.

The photo of the chickens reveals an intimate detail only a careful eye would notice—and it carries powerful emotional weight. It represents one of the many measures the mother turned to in her search for her son—at one point, even fortune tellers. The promise was that the small chicken statues could bring the son back, or at least call his spirit. They sit facing the window, watching or waiting.

In photographing them, Kwok saw not just a false promise, but also a symbol of a mother’s enduring hope—the kind that clings to anything, even a lie, when there’s nothing else left. The photo captures that tension: the space between deception, hope, and faith.

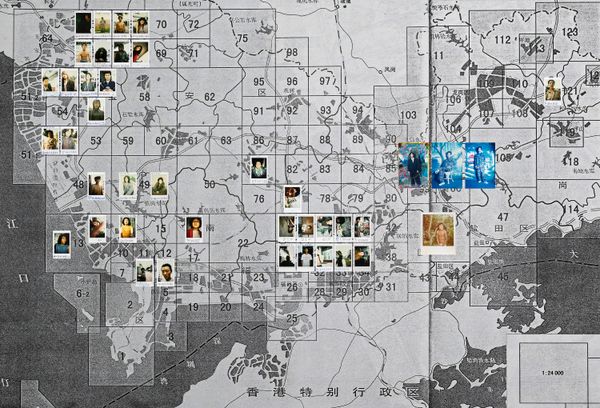

Another striking image is from the mother’s archive: a map surrounded by a cluster of Polaroids. The photos mostly feature portraits of men, faces caught in passing.

When she traveled into China to search for her son, Yu Lai Wai-ling brought an instant camera with her, and in each town she visited, she photographed the homeless people she encountered—a way to rule out the possibility that her son might be among them. The result is a collection of accidental portraits: not a professional undertaking—rather a mother’s desperate search.

“This is a very important thing because she's never a photographer, but she can do it this way as a mother,” Kwok says. “What moves me is that … this is her way, and somehow, it's very creative and very powerful.”

Alongside this personal narrative, Kwok soon started to realize that the story wasn’t only about disappearance—but that it ran a broader theme about identity.

Though the Chinese government spoke of unity—one motherland, one people—the lived reality told a more complicated story. The border, both physical and symbolic, created distance. Systems were different, expectations were different. And through those differences, people’s identities—and their actions—began to diverge.

Kwok’s work moves within that space: between official narratives and private truths, between what the public thinks it knows and what remains untold. It’s a story of loss, love, and of a mother’s relentless search for her son. But it’s also a quiet act of resistance—against erasure, simplification, forgetting.

--------------

All photos © Billy H.C. Kwok, from the series For So Many Years When I Close My Eyes

--------------

Billy H.C. Kwok is a photographer based in Hong Kong and Taiwan, who works at the intersection of art and documentary. His images capture the rapid changes in geopolitical dynamics and the complex power structures shaping his home and neighboring regions.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram.