An Incomplete Guide To Ecological Thinking In Photographic Practice | Vol. 2

-

Published1 Apr 2025

-

Author

How can we effectively minimize the environmental impact of photography dissemination? Utopias Lahti Festival, Loose Joints Publishing, Studio Blanco, Maren Krings, and collective Climate and Cities share their curatorial research and production methods.

This article is part of an editorial series published in collaboration with MPB, Europe’s top camera reseller and its first to publish reports on their environmental and social impact. Aiming to open up the world of visual storytelling in a way that’s good for people and planet, MPB strives to be as circular and renewable as possible, promote inclusivity and diversity and be the most trusted and ethical reseller out there.

In the previous chapter of this editorial series, we looked at how photographers rethink image-making processes in light of the climate crisis. “I believe that the environmental footprint of photographers is negligible compared to the massive impact of corporate-driven consumerism and production”, told us visual artist Mathieu Asselin. “In this broader context, obsessing over the environmental damage caused by photographing feels somewhat ridiculous. However, this doesn’t mean we should ignore the footprint we, as photographers, create”.

The same can apply to the industry of photographic dissemination: for how minimal the impact of exhibitions, photobooks, and photography festivals might be if compared to major players, the interest in ecologically-rooted activities is rising. In conversation with curators, publishers, website designers, and researchers, we assessed how environmentally-conscious methodologies not only serve to decrease our impact but also help imagine new curatorial procedures, opening up unexpected avenues for artistic exploration.

“To make a truly sustainable festival, materiality cannot be a step – it has to underpin everything”: the circular model of Utopias Lahti Festival

Utopias Lahti is a Visual Arts Festival established in Lahti, Finland. Local university students have started joining The Lahti Association of Photographic Artists, which dates back to the early 1980s, to create a platform for experimentation. When Lahti was selected as the European Green Capital for 2021, the ground was fertile enough to pilot their concept: a festival with a strong environmental and social focus, activating under-utilized space in the city, and entirely based on a circular economy.

“We feel exhibition design and materiality in the photographic art community are very restricted fields, dominated by ideals such as permanence and acuity”, says Artistic Director Henri Airo. “Often, the same production methods are used for works meant for museum archives as well as temporary festivals. We were interested in asking what it means to produce a non-commercial festival for lens-based art today, and what aesthetic ideals should be associated with it. Underpinning everything we do are these questions: Are we able to break ties with established modes of photographic production? Could an international photographic aesthetic give way to a plurality of local aesthetics, based on local materials? Instead of works adhering to a single format, should they change when moving globally between exhibition contexts?”.

All materials needed for the festival are sourced locally, most often deriving from industrial excess. “We are building a network of companies, communities, and associations. Their leftover materials form the basis of our exhibition design. For instance, the local newspaper printing press has around 60 meters of newsprint left over every day, which we regularly pick up. In 2023, we collaborated with a local construction company to reuse planks, pallets, and plywood from construction sites. We also produced a handmade inkjet paper with the association Painovoima ry, derived from discarded cotton towels from gas stations. The best part is that we are also able to recycle the prints back into paper pulp, and use them to produce new paper sheets for future editions”.

A twist in traditional curatorial processes is at the core of Utopias Lahti. “Materials are usually only considered during production, after the exhibition concepts and ideas have been discussed. But to make a truly sustainable festival, materiality cannot be a step – it has to underpin everything. Turning this process around is the most effective way for us to work”, says Airo. The resulting installations are often conceived collaboratively with the artists, always in line with the Festival’s ultimate scope. “We gather audiences, artists and artworks in Lahti for a short time to exchange ideas. With this in mind, it feels unnecessary to produce archival-quality artworks that last hundreds of years. Instead, our approach where materials come from different streams, condense into new forms, and then dissipate into new uses afterwards, feels appropriate for this function”.

“We need our books to stand the test of time”: Loose Joints on the responsibilities of resources consumption as a publisher

Loose Joints has been making books since 2014. Over the years, their production has consolidated and expanded. “Not only do we want our books to be sustainably produced, but we need them to stand the test of time”, says co-founder Lewis Chaplin. “If you're choosing to consume resources as a publisher, I think that the books’ completeness and relevance must justify their footprint. This means that there is a vitality to every single publication that we produce, but also that we're not trying to become a publisher that releases 50 titles a year. We're interested in doing ten books, working on them incredibly well, and making sure that they're not some ego-stroking, unnecessary books”.

“We only work with a small handful of printers, which operate in ways that are more sustainable – using FSC certified papers, green energy, avoiding the use of oil-based inks, and sealing books in compostable, biodegradable material”, he adds. “In the past years, we decided to move our production to The Netherlands or Belgium. The supply chain between the paper supplier, the printer, the binder, and our warehouse is reduced to an extremely small amount of space. A book printed there will entail about 500km on the road, versus the 2500km of transit for a book produced in Turkey or Lithuania”.

During his talk at “The Photobook Ecosystem: Searching for Sustainable Approaches” organized by 10x10 Photobooks, Chaplin pointed out the significant waste of offset printing, as machines need paper to run before they can efficiently distribute ink. “If you are working at a smaller scale, digital can be a very good idea”, he comments. “Over the last 15 years, its quality has started to catch up. Trinity by Oliver Raymond Barker was an interesting experiment for us. It's a completely handmade book, made with a majority of recycled materials, digitally printed in 250 copies. To be honest, I can't tell the difference that much”.

Another key concern is the aftermath of unsold books. “Destroying remaining books is a very common practice in the publishing industry”, says Chaplin. “It is really important for us to avoid doing that. This is why if you buy two books on our website, you get a free one – those are books that were probably not going to get fully sold. This way they still can keep reaching people”.

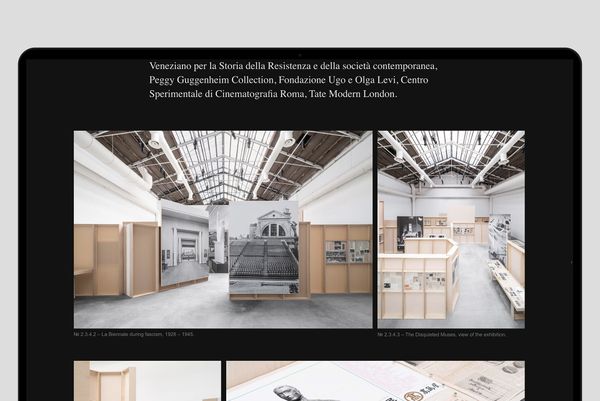

“We aimed to keep people on the site for as little as possible”: Formafantasma’s website designed by Studio Blanco to minimize CO2 emissions

“It’s important to clarify that the most sustainable website in the world is probably a static, single-page, dark-mode site with minimal text. Anything beyond that is a compromise between communication, commercial needs, and practices that aim to reduce digital pollution”, says Valerio Tamagnini, Creative Director at Studio Blanco. In 2020, design studio Formafantasma asked them to design a website minimizing its energy consumption and CO2 emissions. “Formafantasma wanted to explore this issue as deeply as possible. The most interesting aspect was the shift in mindset and approach we adopted from the very beginning. We aimed to create a site that represented their work effectively while simultaneously keeping people on the site as little as possible. It’s unusual because most websites aim to do the opposite – keeping users engaged for as long as possible, encouraging navigation and clicks”.

“The entire site was structured to provide information as quickly, clearly, and precisely as possible without unnecessary distractions”, explains Tamagnini. “For example, the landing page is text-based and immediately presents the full site architecture, making all main sections and subsections clickable without loading unnecessary content. The website uses system fonts, features a dark mode, and shows users a preview of the average file size they will need to download when hovering over an image before viewing it at full size. Additionally, the website is hosted on a platform that uses renewable energy sources”.

What can a photographer do to design their website more consciously? “If an artist is not defined “only” by their work but also as an individual with a philosophy or point of view, they might consider using some words to describe it upfront”, says Tamagnini. “This could help avoid unnecessary clicks or the loading of web elements that aren’t particularly relevant to the user. Additionally, implementing a default dark mode and using a system font to reduce loading times are other simple steps that can easily be integrated”.

“A monochromatic color scheme, and works fading after four weeks”: Maren Krings’ exhibition at Fonderia 20.9, transported by bike from Austria to Italy

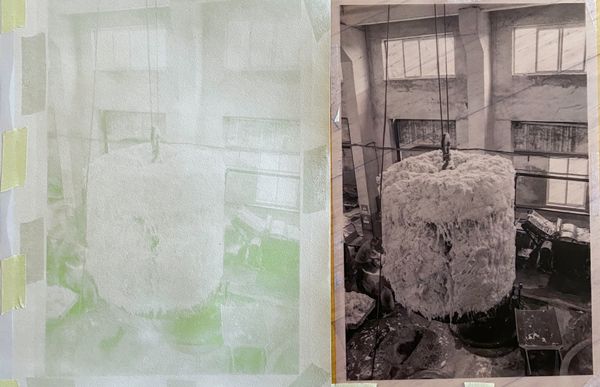

Maren Krings describes herself as a “climate impact storyteller”, actively engaged in mitigating the current climate crisis. Her exhibition H IS FOR HEMP. A Green Art Extravaganza, curated and produced at Fonderia 20.9 as an outcome of the PhMuseum 2023 Photography Grant, radically examined the dynamics of exhibition conception and production.

“The first room exposed visitors to three works on hemp paper, printed with Cannabis sativa L. plant-derived colors. They were unframed, secured with small magnets adhering to metal screws in the wall. This non-invasive hanging method preserved the integrity of the paper while offering a lightweight solution for transportation: the packaging was reduced to a single plastic tube and a backpack that I could carry on trains and by bike. Due to the ephemeral nature of the anthotypes, which fade within a month, I reused the same papers for two additional shows that followed in 2023”, explains Krings. “At the center of the exhibition, a green energy station was installed, consisting of a bike connected to a home trainer. An adaptation on the back wheel ensured the generation of 100% human-powered, green energy. Pedaling the bike activated a transformer that powered a UV-LED grow light. Positioned in front of the bike, a worktable held cannabis-color-coated paper prepared for UV light exposure. This participatory installation invited visitors to engage in the anthotype exposure process while prompting reflection on energy use and its origins. Eventually, a travel log encouraged visitors to record their journey to the gallery. This data allowed me to calculate the attendees' approximate carbon footprint, contributing to the exhibition's overall impact assessment.

The bike stands as a symbol of the exhibition’s ethos. “Despite unfavorable timing for bringing works from Tyrol, Austria, to Verona, Italy, I managed to deliver the exhibition by bike”, says Krings. “A late-season snowstorm in Tyrol a day before departure forced me to take a train across the Brenner Pass, and I took another for the final stretch to Verona. While the journey was physically demanding, I was very proud of sticking to this plan”.

Thinking ecologically when designing an exhibition means adjusting its logic to completely different criteria, Krings explains. “We had to reconcile our expectations for a professional show with the limitations of sustainable production. These included a monochromatic color scheme, works fading after four weeks, and the inherent constraints of the anthotype process, where not all negatives produced the desired results. Shifting our mindsets to embrace and display mistakes openly was a pivotal and courageous step for both the curators and myself. The exhibition became an open-source environment, showcasing honest outcomes – flaws and successes alike – to the audience”.

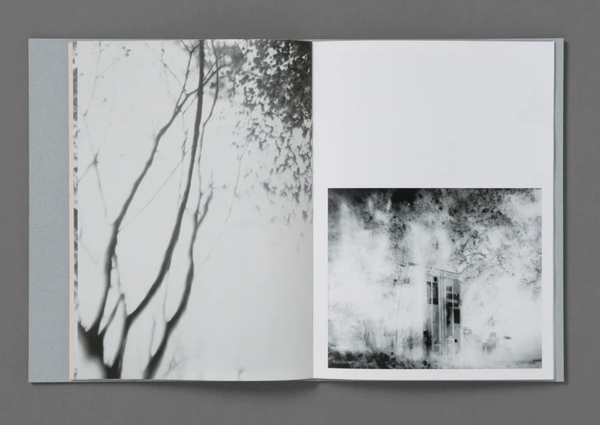

“Nuance rather than absolutes”: the Creative Climate Investigations Book questioning sustainability as a practical process

Climate and Cities, a creative collective based in London, has always been focused on re-writing narratives around the climate and the urban environment. In 2022 their 2.5 years-long research, analyzing greenwashing, air quality, and the ecological impact of data, culminated in a printed publication whose production questioned sustainability as a practical concept. “We embraced nuance rather than absolutes”, says Rebecca Lardeur. “Instead of seeking a perfect solution, we focused on making informed, mindful choices”. Printed in a small run of 100 copies, the Creative Climate Investigations Book presented all the struggles of a production that is neither fully industrial nor hand-made. “Rather than seeing limitations as obstacles, we leaned into them. We didn’t find barriers on the technical side because we worked within the realities of what was available”.

Speaking more broadly, sustainability often presents challenges that are so entangled they seem paradoxical. “We needed to balance carbon reduction with circularity—two goals which more often than not are at odds with each other. A lower-carbon choice might not be circular, while a fully circular option could have a higher carbon footprint. Rather than prioritizing one over the other, we navigated trade-offs case by case. For example, we wanted to avoid fossil fuel-based materials, but nylon thread lasts longer than biodegradable cotton. Our compromise? Using salvaged nylon thread instead of sourcing new materials. Similarly, we opted for risograph inks, made from vegetable oils, to reduce plastic-based digital inks, even though it required design adjustments”.

“Each choice was questioned, tested, and reworked where necessary”, she adds. “We printed locally with Folium Publishing in South Bermondsey, avoiding unnecessary transport emissions. The book’s size was adjusted to fit the printer, reducing offcuts and waste. We sourced recycled paper from a London-based supplier. Throughout production, we tracked emissions, prioritized reductions, and traveled by public transport. Forecasting our carbon footprint early in the design phase allowed us to identify areas for reduction before finalizing decisions”. The carbon footprint of each book was estimated to be 1kg CO2e, against the 3k average they assessed. The relationship with printers and manufacturers was central to this aim. “Asking questions to the experts who work every day with materials is key, being actively curious about them—where they come from, how they’re made, and their impact”.

Almost three years later, the collective is now primarily engaged in understanding how to print a book without the help of fossil fuels. “Our curiosity stemmed from a simple truth: we must stop using crude oil by-products. Paper bleaching, PVA glue, digital inks, and nylon thread are all embedded in fossil fuel dependency. This time, we are all collaborating on a single investigation instead of multiple researchers working independently. While it’s a different focus, the ethos remains the same—questioning what’s taken for granted and pushing for better ways of being”.

In short: tips, thoughts and processes in design, publishing, curating, and producing

Work locally and create networks: prioritize local sourcing, getting in touch with businesses to access their industrial leftovers.

Focus on materiality: it is a key curatorial element, and not just a production phase.

Think of circularity: how can materials take a different shape after you've used them?

Quality over quantity: produce less, yet more thoughtfully.

Choose the right technical partners: aim for printers who use FSC certified papers, green energy, avoid the use of oil-based inks, and seal books in compostable materials.

Consider your supply chain: how can transportation between in your production be reduced to the bare minimum? Can you prioritize public transports?

Consider digital printing: it can be a more sustainable option for smaller runs.

Design websites for efficiency, not just engagement: use system fonts, a dark mode, and text-based, clear information to minimize navigation and clicks.

Transparently assess your impact: you can track and share your activities' carbon footprint.

Accept limitatons: display and share your process, including mistakes.

Engage with experts: be curious about materials, and collaborate closely with printers and manufacturers.

Embrace nuance: recognize that sustainability involves trade-offs and there are no perfect solutions.

--------------

About MPB

For over 10 years, MPB has made used photo and video gear more accessible. With experts in Berlin checking and individually photographing every item, MPB offers camera equipment you can trust, with a free six-month guarantee for added peace of mind.

More than half of us have a camera at home we’re not using. Find out exactly how much your kit is worth with a free instant quote from MPB. Take advantage of free, insured shopping to send in your gear, and get paid directly into your bank account.

--------------

Useful Resources

The Sustainable Photobook Publishing (SPP) network: a group of photographers, publishers, academics, and writers sharing knowledge around environmentally conscious approaches to photobook publishing.

GCC (Gallery Climate Coalition): an international community of arts organizations working to reduce our sector’s environmental impact.

THE PHOTOBOOK ECOSYSTEM: Searching for Sustainable Approaches: a panel discussion organized by 10x10 Photobooks and the SPP Network with Lewis Chaplin (Loose Joints), Catriona Gourlay (National Arts Library, V&A Museum), Tamsin Green (manual.editions, SPP Network) and Paul John (Jan van Eyck Academie, Endless Editions).