Amy Kim’s West Texas: Landscapes of Labor, Symbols, and Change

-

Published3 Jul 2025

-

Author

Documenting a region transformed by oil, money, and technology, Amy Kim reveals the layered visual and social complexities of life in West Texas.

For years, Amy Kim lived just two hours from the West Texas oil fields she would later photograph. But when she moved to the area after attending Texas Tech University, the place felt entirely different—both in atmosphere and identity. What seemed close on a map revealed itself to be a world apart.

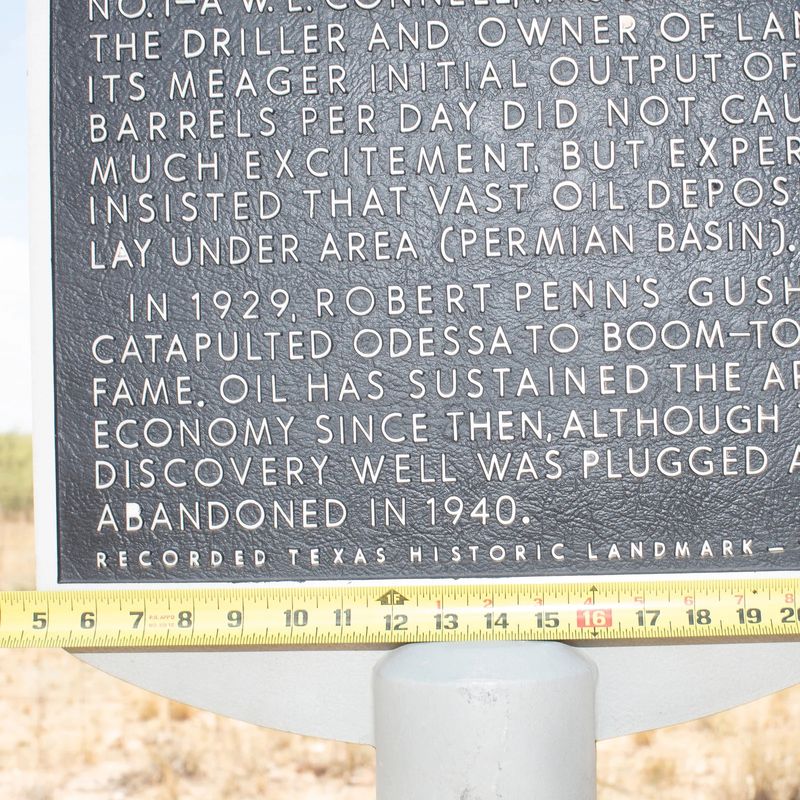

At the heart of this landscape lies the Wolfcamp Shale, beneath the Permian Basin—a geological formation stretching across 86,000 square miles of desert in West Texas and eastern New Mexico—the most lucrative oil-producing site in the world.

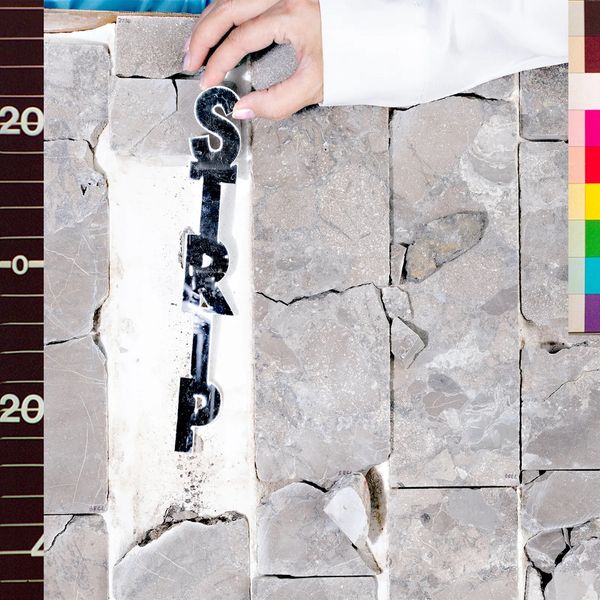

Kim’s project, Wolfcamp Catalogue, probes the myths that sustain this engine of industry—challenging the technological, political, and cultural structures that orbit around oil and gas. Her photographs lean on visual signifiers—fragments of daily life, labor, and landscape.

Kim arrived just before the pandemic, at the height of an economic boom fueled by oil production, deregulation, and new extraction technologies. Towns that had once felt abandoned now pulsed with industry money: Hotel rates soared, rents climbed, a sense of prosperity in the air. The scale and speed of the transformation compelled Kim to begin documenting what she was witnessing.

Trained in theater, Kim’s eye searched for stories shaped by her surroundings. This wasn’t just a landscape of industry—it was a stage layered with visual cues and symbolic markers. “When you get there, there are so many visual signifiers,” she says. “Foreign structures, equipment, the way people dress, the housing… It’s its own sort of, I want to call it in a way, kind of its own kingdom.”

At the heart of this kingdom were the "man camps"—temporary housing sites for oil field workers. Some were modest, trailer-park-style setups; others lavish, featuring dining halls and swimming pools built right in the backyards. Rising above it all were the oil rigs, hundreds of feet tall, and the ever-present fire stacks, roadside chimneys burning off excess gas.

But the strange contrasts didn’t stop at the landscape. Kim was struck by the unexpected details of daily life—like the mundane, near-ubiquitous presence of Louis Vuitton bags, carried across social classes and spotted everywhere from small grocery stores to neighborhood streets. These surface symbols became part of what Kim calls her structuralist approach: letting form and visual detail lead, allowing the images she gathered to shape the narrative meaning over time.

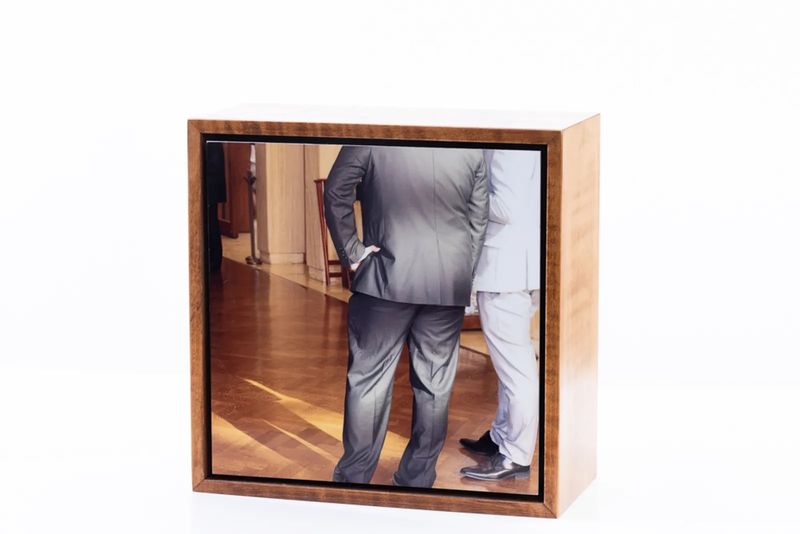

Her interest in surface and structure soon deepened into questions about labor and society. Kim reflects on how the area seemed to visually enact Karl Marx’s idea of superstructure and labor: a place where divisions between work and display felt especially stark. Yet the scene unfolded against a backdrop of fierce anti-socialist fervor, adding a layer of irony that weighed in Kim’s contemplations.

Kim’s method was deliberate, even ritualistic—stopping every three miles along the highway, echoing Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations poetic approach—letting the road itself dictate the journey. This cadence wove structure into the visual story, a steady heartbeat anchoring the work.

Archival research added another layer. Her project gathered echoes of the past as Kim sought out photographs from local libraries, museums, and state archives across Texas, weaving historical imagery into her work. More recently, her focus has turned toward family photos from local residents—snapshots of oil field workers and neighborhood life, passed down across generations, now all the more precious in an era when few people print their photographs.

Her project pushes beyond industrial sites, touching on family rituals, neighborhood rhythms, and the ways labor and personal life blur together in the fabric of the region. The area’s strong Hispanic presence adds yet another dimension to her exploration of identity, history, and place. For Kim, the project has evolved into an anthropological inquiry, tracing the connections between people, labor, land, and even prehistoric geological formations—the ancient origins of the fuel that now defines the region’s economy and landscape.

What began as visual documentation became something more reflective. Kim describes the pleasure she found in the quality of the West Texas sunlight, and in the vast, empty stretches of desert that offered her a kind of anonymity and solitude during her fieldwork.

Ultimately, Kim doesn’t want to offer easy answers. Her hope is that viewers leave her work carrying the same complexities she wrestled with while making it—a sense of gentle unrest. “I want the viewers to leave the work feeling very contradicted, through my efforts in parsing some of this through,” she says. “I want them to take that contradiction into thinking about their own perspectives in their own living.” Rather than resolution, she wants them to sit with the discomfort, puzzling over their own relationship to place, labor, and identity—emerging, perhaps, just a little changed.

--------------

All photos © Amy Kim, from the series Wolfcamp Catalogue

--------------

Amy Kim is a full-time faculty member and director of gallery at UT Permian Basin Department of Arts in Odessa, Texas, with an MFA from Texas Tech University’s School of Art. She is an American-born Korean, and has lived in South Korea and Michigan, and currently resides in Lubbock, Texas. Find her work on PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram.