An Incomplete Guide To Ecological Thinking In Photographic Practice | Vol. 3

-

Published7 May 2025

-

Author

Paola Di Bello, Roberto Huarcaya, Miguel Sbastida and Aindreas Scholz's works inquire into the relationship between ecosystems and image-making techniques, turning photography into a way to tie bonds with the non-human.

This article is part of an editorial series published in collaboration with MPB, Europe’s top camera reseller and its first to publish reports on their environmental and social impact. Aiming to open up the world of visual storytelling in a way that’s good for people and planet, MPB strives to be as circular and renewable as possible, promote inclusivity and diversity and be the most trusted and ethical reseller out there.

Read the two previous articles of An Incomplete Guide To Ecological Thinking In Photographic Practice: Vol.1 and Vol.2.

The first photobook in history, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843) by Anna Atkins was a collection of marine specimens addressed to the scientific community. The plants were being physically pressed onto light-sensitive paper, leaving a mark of their presence over shades of blue. Silver was not involved in the process. In the background, carbon emissions began their rise, marking the beginning of a climate crisis that was yet to be perceived, studied, and discussed.

Today, looking at Atkins' work from the inside of an environmental breakdown, its ecological value appears of the utmost urgency. Not only were her Cyanotypes an example of a more sustainable way of making images, but they were also testifying to a possible fruitful relationship between photography and science. As visual artist Lucas Leffler stated in the first article of this series, "alternative photographic processes began to gain traction in the early 2010s as a reaction to the widespread adoption of digital tools. Interestingly, it was the same digital tools— for example through online communities—that facilitated an interest in older techniques".

We turned to photographers and visual artists whose practice deeply engages with ecological thinking. They employ photography not only as a representational tool but also as a way to tie bonds with what is more than human.

“Ecology means paying constant attention to the marginal, to the forgotten, the repressed”: Paola Di Bello’s impressions of fireflies on photographic paper

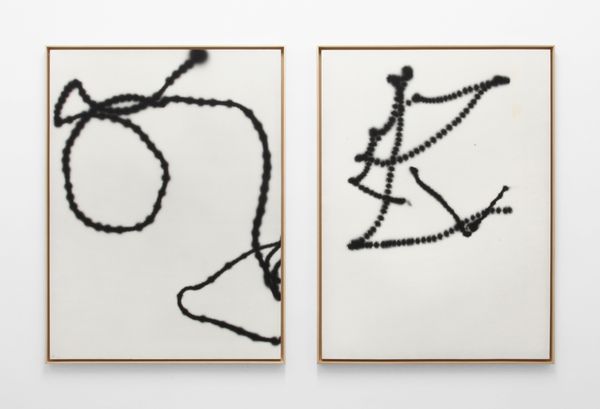

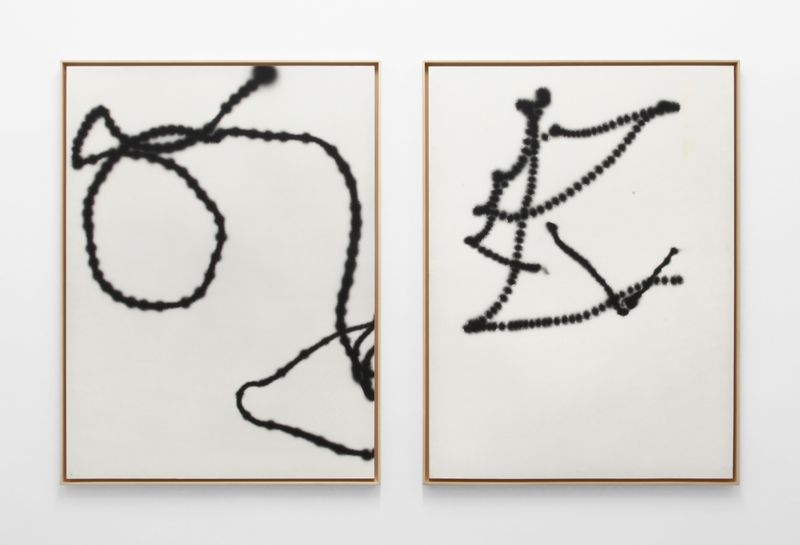

In Paola Di Bello’s work Fireflies, living beings physically mark their passage on paper. The resulting images – black, seemingly random paths over a white background – open up a series of questions: What does it mean to make art with living beings collaboratively? How to set the right conditions for this to happen? What can the fireflies teach us?

“On the night of June 29, 1988, I collected 25 fireflies in an unpolluted area in the countryside around Pavia, about 30 km from Milan”, explains Di Bello. “I placed them in a special container stocked with nourishment – grass, water, and sugar – and transported them to my darkroom in Milan. Here I let the fireflies walk freely, alone or in groups, over 18×24 cm black-and-white photographic film. The next day I released them in their original environment, and developed the films. Walking on the photosensitive emulsion, they left a black mark. What interested me was getting closer to something fundamental. I only set initial conditions so that the image could take shape by itself – or better, without me.”

The resulting images help us question our understanding of the non-human. Di Bello references Stephen Jay Gould and Ed Purcell: “They taught us that while stars are randomly distributed in space, and yet we see figures in them, the trajectories of fireflies have no randomness to them. Even though we cannot read through their patterns, they are dictated by specific needs. We know nothing of those light trails and their meanings”.

“With fireflies, I experienced a real shift in the conditions of image-making”, she adds. “Very often, slipping to the side of things allows unanticipated possibilities to emerge”. This ability to reconsider our paradigms is, after Di Bello, at the very root of ecology. “Ecology, for me, is not confined only to environmental discourse. It is a way of being in the world. I have always sought what I might call an ecology of the gaze, and therefore an ecology of images – which I believe is very important today. To me, doing ecology in art means not so much having made work with fireflies, but rather paying constant attention to the marginal, the forgotten, the repressed. To all that we habitually push beyond the margins of the visible because it is too painful, or because it makes us powerless, frightened in the face of a reality that is increasingly hard to read”.

“Art can be an incredible ally of science”: Miguel Sbastida’s transmedia narratives of ecosystems and timescales

A glacier maps its erosion on blue-tinted sheets of paper, strategically placed underneath its melting areas. The shores near Bilbao become a site for the analysis of industrial waste, dumped in the Cantabric Sea between 1920 and 1970 by the metallurgic industry Altos Hornos de Vizcaya. These are some of the ecological narratives activated by Miguel Sbastida across installation, performance, photography and video. As a whole, his practice is an attempt at connecting us with specific ecosystems, tuning in timescales that are different from ours.

“Artists play an instrumental part in the construction of the metaphors we live by”, he says. “Art can be an incredible ally of science because data is oftentimes cold, highly technical, and difficult to understand”, says Sbastida. “Think about big concepts, like climate change or the Anthropocene. They are interconnected, complex, difficult-to-understand ideas, and their scale often freezes the mind and the body. The experience of art, on the contrary, situates the viewer in the middle of an emotional response that can trigger something else”.

The way Sbastida describes his work transcends the boundaries between different disciplines or methodologies. Every element brings ecological thinking into action. “There are so many strategies that I have been employing and testing over the last decade to reduce the footprint of my work. From the most basic choices pertaining to material use, to more sophisticated ideas related to transport, the people you collaborate with, or the design of positive-footprint artworks that help restore ecosystems. In many of my projects, I have chosen to take much longer and expensive production to avoid toxic materials or byproducts. In some projects we also established a code of compensation, so that a percentage of sales had to be donated to environmental conservation initiatives”. “Not every artwork is ecological even if it refers to the natural world, and that is fine", he adds. "Just be patient, if those ideas are inside of you, they will find ways to manifest into the work. The rest is all bureaucratic, and entails demanding your gallery or curator to consider shipping with that other carrier, fabricate locally or invest funds into supporting actions outside of the arts that can create new forms of ecological collaboration or collective thinking. Don't get burnt out: we need you to keep talking about this”.

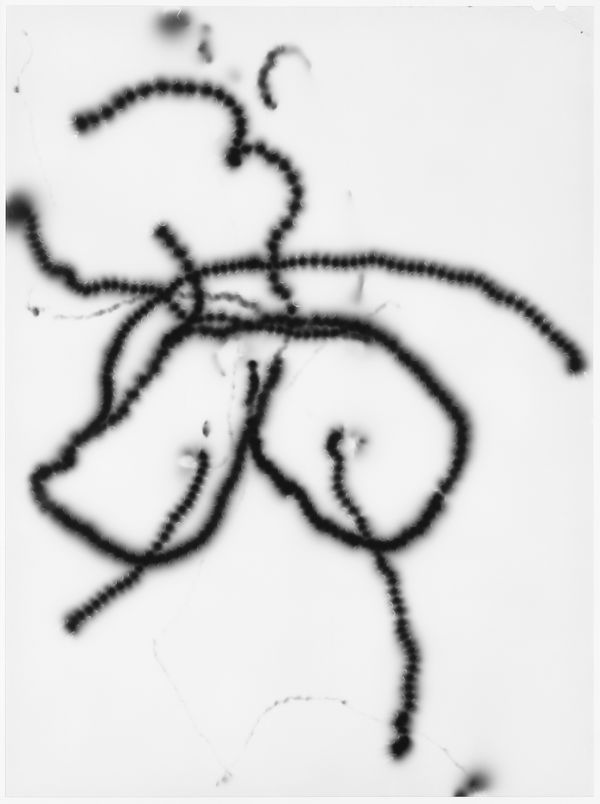

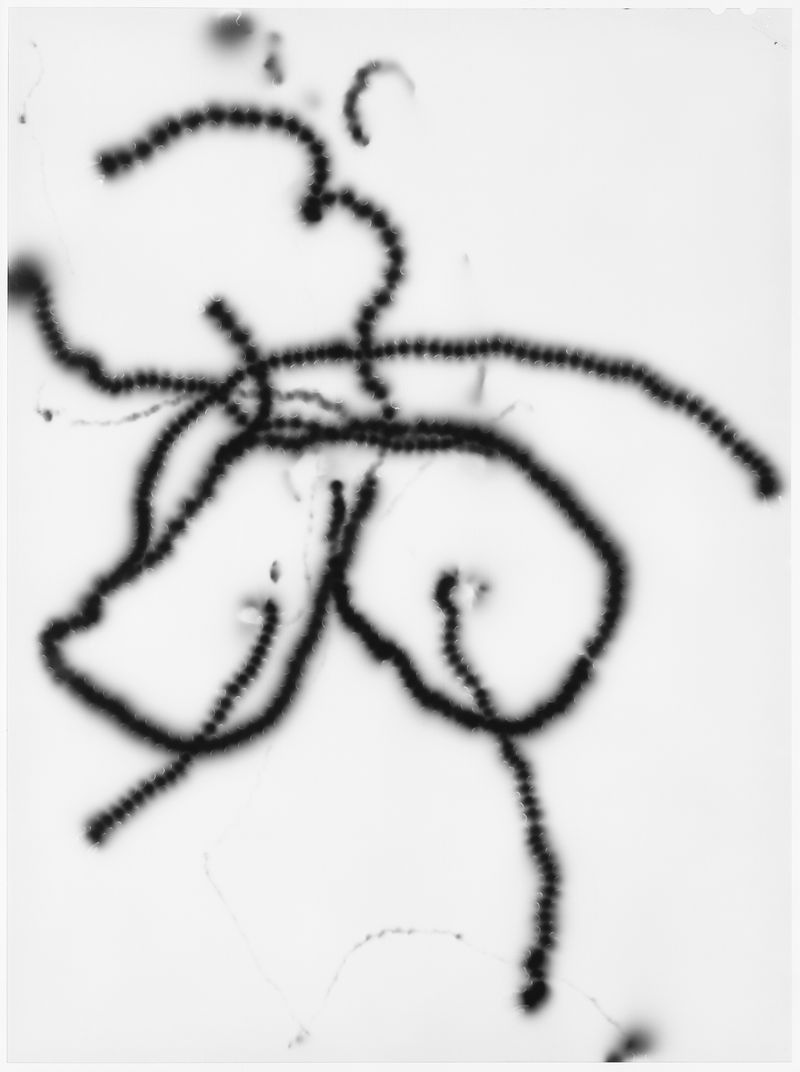

“A horizontal technique that touches nature”: Roberto Huarcaya’s monumental photograms of the Peruvian Amazon

Roberto Huarcaya’s photograms - pictures produced by directly placing objects onto a photo-sensitive paper - are the outcome of extensive research in the Peruvian Amazon. They came after “two years of failures”, as Huarcaya describes them: a veritable crisis with photography and its way of rendering reality. “A necessary distance existed between the camera and the Amazon”, he says, “allowing for one point of view only - that of the photographer. I only managed to record the epidermis of the jungle, yet the Amazon was much more than that”. The direct touch implied by photograms filled and canceled that distance. Plus, the use of large frames of up to 30 meters could represent extended and multiple points of view. “When I returned to the Esajes’ shaman with the first photograms, he told me: ‘Roberto, it has been interesting to see how you have been unlearning the burdens of your culture. Now you found a more empathetic and horizontal technique that touches nature, thus Nature has decided to settle on your paper, so that you can show it to your people’.”

How are Huarcaya’s photograms made? “First, I start by choosing the time of the year to work on, considering the rainy season, full moon week, storms… I enter the jungle during the day and walk, looking for areas that attract me for their density and type of foliage. Then we stick bamboo stakes about two meters high, marking the route where we will hang the photo-sensitive paper later at night. Finally, we will expose the piece. We work with a small handheld flash, with the moonlight in very long exposures, or with storm lightning. After, we process the paper by mixing the chemicals with river or seawater. The development of 30-meter pieces reaches up to 7 hours of continuous process, involving at least 6 people. Sometimes we leave some of these pieces for up to a year so that they continue to change. Eventually, we wash again, re-fix and do a selenium bath to consolidate the stability of the piece. All the chemicals return to Lima and are disposed of ecologically”.

This methodology comes with high degrees of unpredictability: nature will always come in the way, ridiculing any preconceived thought or plan on what an image should look like. “I accepted all incidents and accidents. I assumed them as part of the work, and not only that: they now are essential to it", he says. “There has been a shift from the idea of a monolithic author to an author who serves as a catalyst, so that various experiences can be exposed. The intrusions of nature are more than a problem: they are opportunities to reinvent ways of doing things. This is the only advice I can give: be honest with your processes. You need to respect intuition as an immeasurable tool of creation, and pay attention to it. You need consistency over time, none of the immediacy that our culture has accustomed us to".

“Artworks shaped by chance, time, and weather”: Aindreas Scholz’s practice across Cyanotypes, Lumen Printing, Cyanolumen and Soil Chromatography

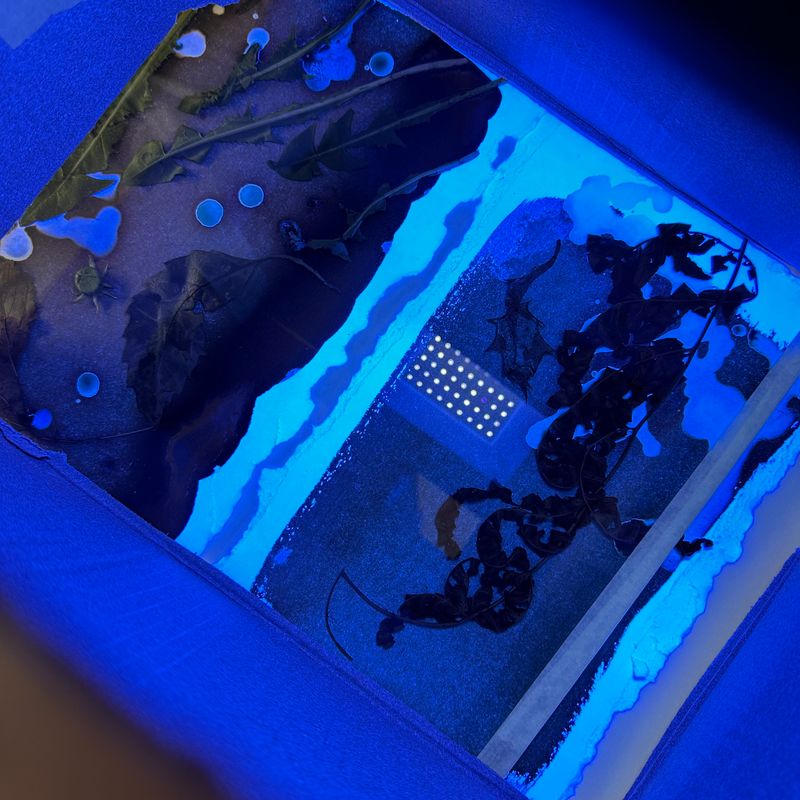

The environment is an active participant in Aindreas Scholz’s artistic practice, which spans multiple alternative darkroom techniques. They share “a tangible, almost alchemical quality: you can watch the reaction happen right before your eyes”. “The methods I employ rely heavily on sunlight and natural pigments, significantly reducing or at times eliminating toxic chemical usage”, he explains. “I work with Cyanotypes, a blueprint process using iron-based salts and minimal water, or with Lumen Printing, a silver-gelatin-based process in which objects are placed on exposed or expired darkroom paper, and then exposed to sunlight – a way to re-use waste materials without requiring extra chemical steps. Cyanolumen is a hybrid method in which I place plant specimens on waste darkroom paper that’s been pre-coated with cyanotype solution, then expose it to sunlight. Last, Soil Chromatography uses filter paper pre-treated with silver nitrate and soil. The process relies on capillary action rather than harsh chemicals”.

The interplay of these techniques produces organic works where “chance, time, and weather shape the outcome, somehow removing my ego from the equation”. One example is And So I Watch You From Afar, a project that “took place in different regions, each facing climate challenges: the increasingly subarctic and rain-soaked Shetland archipelago, the vulnerable low-lying coastlines of the Danish Baltic Sea, and the drought-prone yet periodically flood-stricken areas of the Middle East. I worked with archival watercolour paper for its recyclability and durability, and coated each sheet with a cyanotype solution mixed with collected seawater or rainwater. Plant specimens, soil, silt and sand sourced from a local coastline were arranged on the paper. The coated sheets were exposed to direct sunlight from a few hours to several days. After, the cyanotypes were gently washed in seawater or rainwater. This process produced a series of works reflecting each region’s rich and fragile geographical diversity”.

In short: tips, thoughts and processes toward a more conscious practice

Collaborate with other species: see non-human entities as an active agent, and not as a subject.

Accept unpredictability: allow natural elements such as sunlight, time, weather, or living beings to influence and shape your work, leading to unanticipated outcomes.

Attend to the marginal: pay attention to the overlooked, repressed aspects of reality, representing what is usually left out from established narratives.

Art as an ally of science: think of how you can address scientific data through your work, making out-of-scale concepts more relatable.

Make positive-footprint artworks: consider how your production can help restore the ecosystems it

deals with, for example by establishing a code of compensation regulating the funds raised with your work.

Work locally: source your materials from the specific environments you are working in.

Accept longer paths: very often, avoiding toxic materials and byproducts needs longer, more expensive productions.

Reduce chemical use: through techniques such as lumen printing, cyanotypes, cyanolumen, or soil chromatography you can employ natural pigments and sunlight rather than chemicals.

Don't get burnt out: Your engagement in ecological art-making is much needed: be consistent over time.

--------------

About MPB

For over 10 years, MPB has made used photo and video gear more accessible. With experts in Berlin checking and individually photographing every item, MPB offers camera equipment you can trust, with a free six-month guarantee for added peace of mind.

More than half of us have a camera at home we’re not using. Find out exactly how much your kit is worth with a free instant quote from MPB. Take advantage of free, insured shopping to send in your gear, and get paid directly into your bank account.

--------------

Useful Resources

The Sustainable Darkroom: an artist-led, research community that develops low-toxicity chemistries and practices in photography.

MPB Meets Alice Cazenave: The Darkroom Innovator Making Film Photography Eco-Friendly

Alternative Processes: learning platform and community for historical, experimental and sustainable photographic processes.

The Sustainable Photobook Publishing (SPP) network: a group of photographers, publishers, academics, and writers sharing knowledge around environmentally conscious approaches to photobook publishing.

GCC (Gallery Climate Coalition): an international community of arts organizations working to reduce our sector’s environmental impact.

THE PHOTOBOOK ECOSYSTEM: Searching for Sustainable Approaches: a panel discussion organized by 10x10 Photobooks and the SPP Network with Lewis Chaplin (Loose Joints), Catriona Gourlay (National Arts Library, V&A Museum), Tamsin Green (manual.editions, SPP Network) and Paul John (Jan van Eyck Academie, Endless Editions).