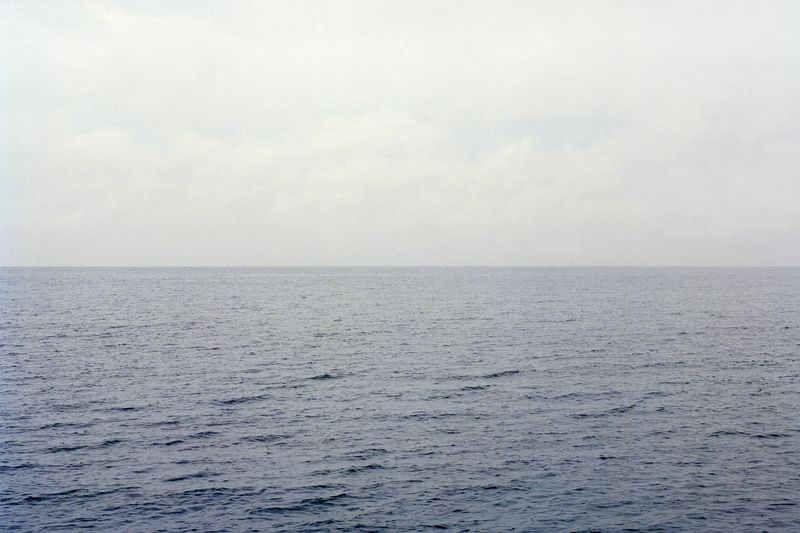

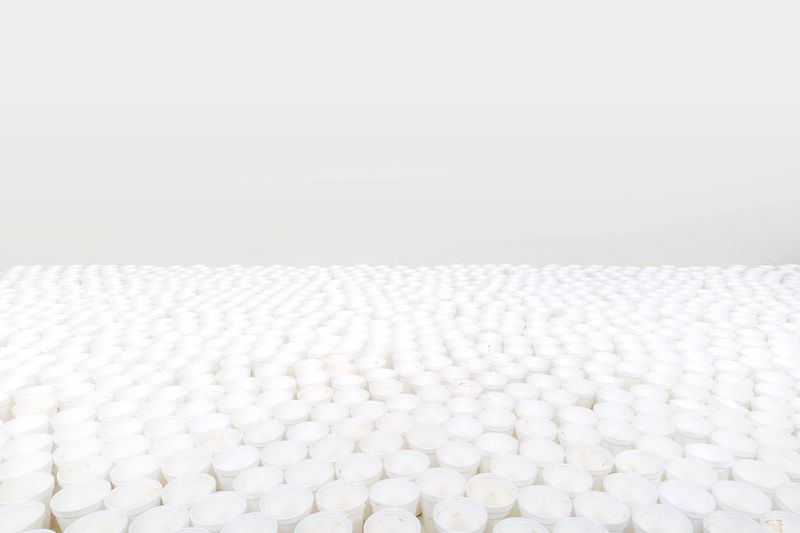

To Set Fire to the Sea

-

Dates2016 - 2018

-

Author

- Location Australia, Australia

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

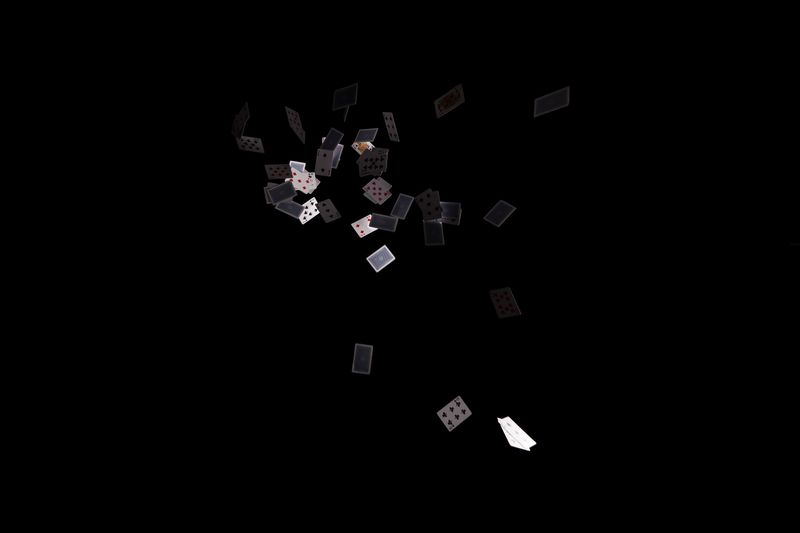

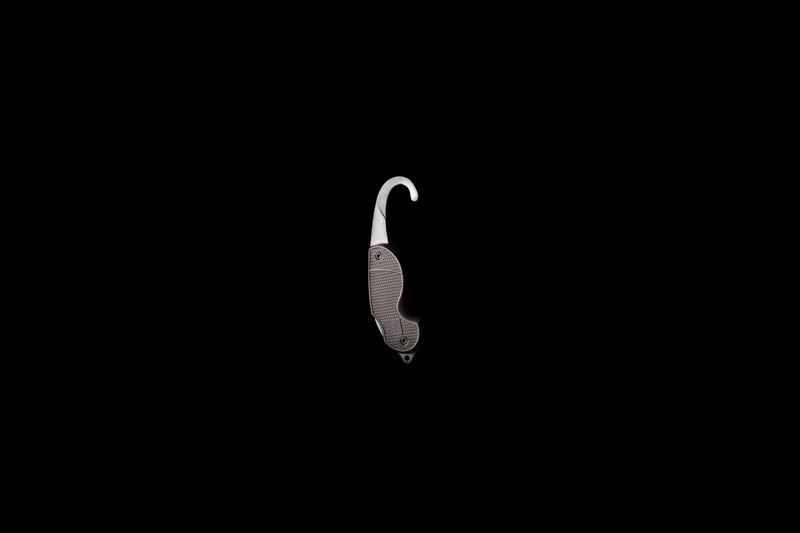

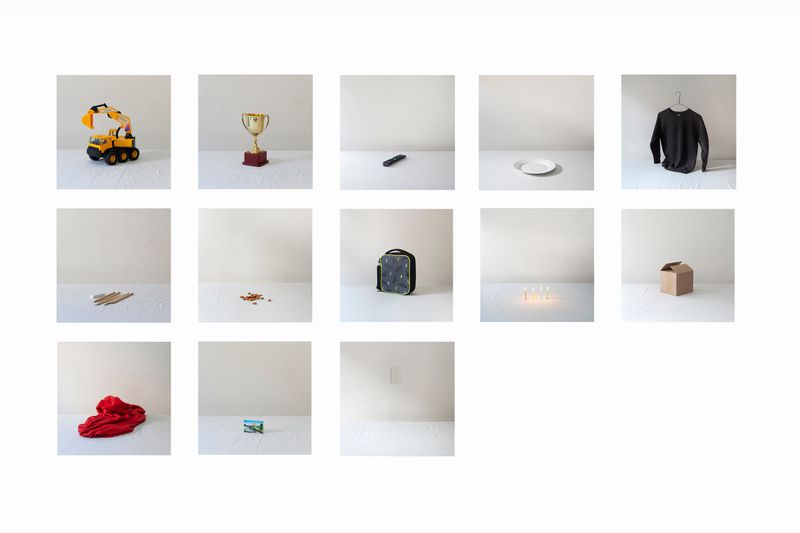

To Set Fire to the Sea explores the Australian Government's policy of mandatory and indefinite detention for asylum seekers.

These stories are fragments from the ongoing life and conversations with friends who are in detention centres, have been 'released' into community detention, or have temporary asylum in Australia.