Untitled, India

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location New Delhi, India

-

Recognition

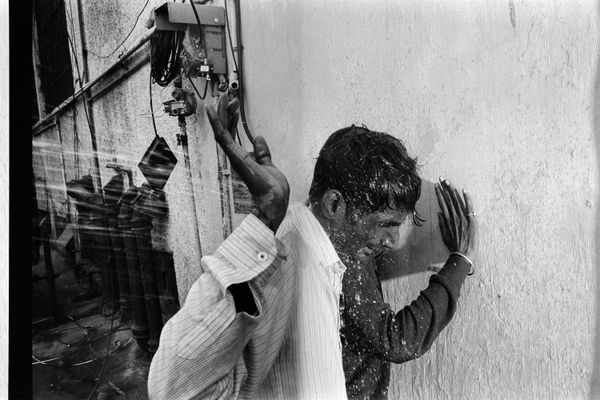

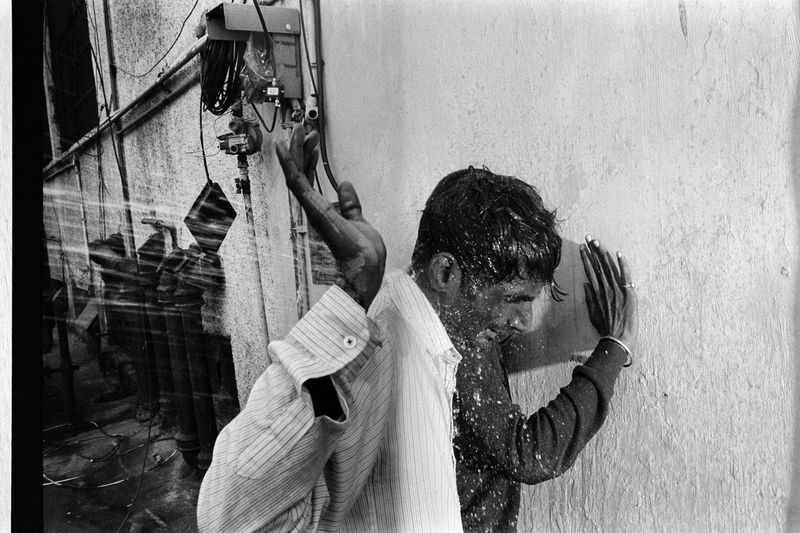

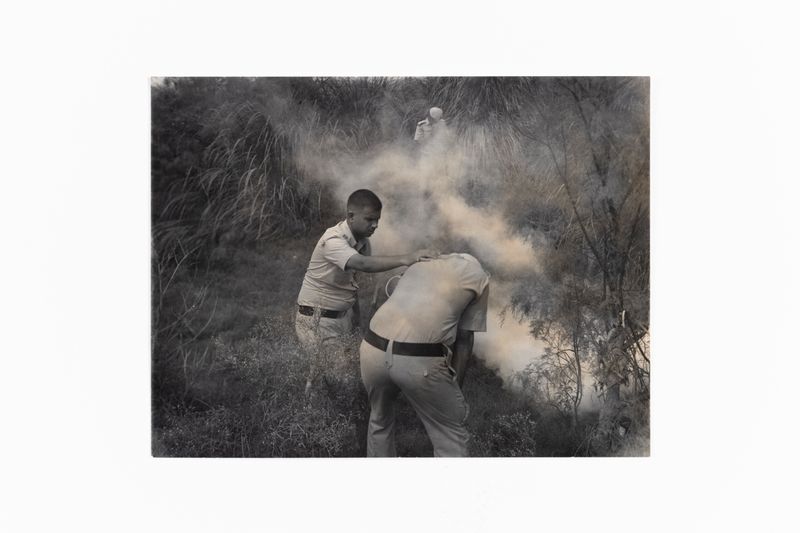

Untitled, India questions the limits of witnessing. I photograph landscapes in New Delhi marked by protest and erasure. The work lingers in the provisional—where looking is uncertain, where presence remains conditional.

Journalistic imagery within India is predominantly mediated through the male form. This, I gather, is because documentary, in its purest form, is tethered to the street.

In the Civil Contract of Photography, Ariella Azoulay writes: - "In the course of adolescence, these warnings were joined by a long series of prohibitions concerning me as a girl, as a woman. An entire world of moving freely through space and its related adventures had been gradually placed beyond my reach, because these had always involved walking at night, entrance halls, and public parks."

Over time, I have understood that the street can never be my backdrop; the street is never permitted. The photographs in Untitled, India I stage with a desire to account for witnessing — my witnessing — an inquiry prohibited both by news media censorship and a gendered denial of access.

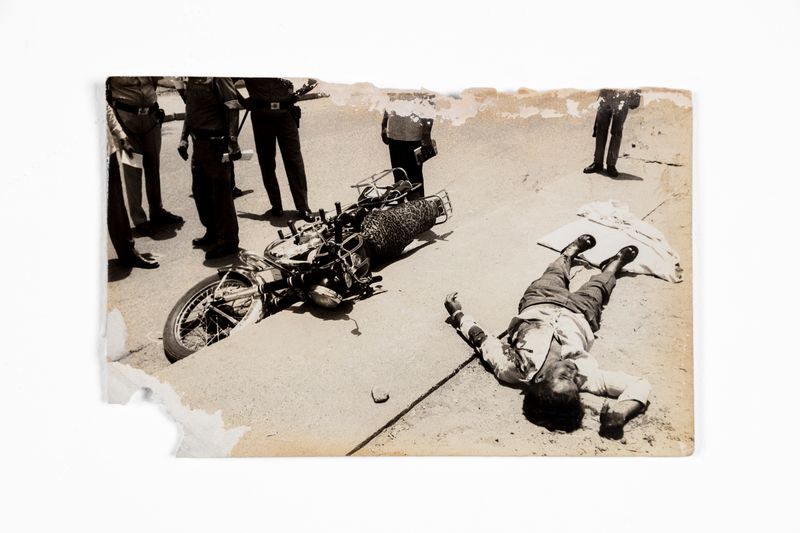

What is then required of imagery that is made after the fact? Should it be conceived as a practice of necessity — an account of that which is withheld? And how does one mimic the exhaustions of events contained within the documentary photograph?

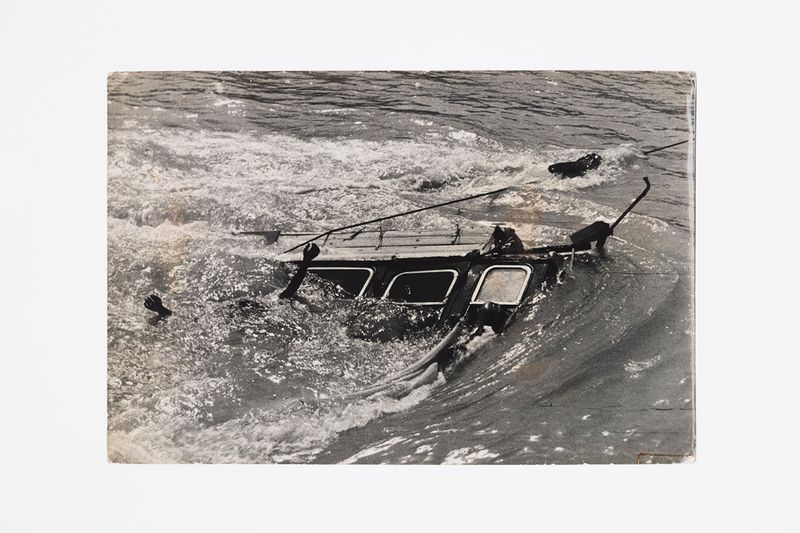

In 2024, multiple international news forums recirculated an image of Delhi’s heatwave— first used in 2022. Its title was casual — no pointers to place or condition. It read like visual training in dehumanising the fact; a landscape imaged to exhaustion, its meaning decentered. I began to seek out these same landscapes; they became my stage. My collaboration with actors I deem necessary for this replication: they are actors who have either been subjected to or witnessed, instances of aggravation and brutality. Another aspect of my work is the darkroom; I print my images on discontinued paper and bring them to an aging chamber, to replicate the materiality of the archive. In their showing, I mix them with images found at a secondhand market, their source unknown.

Sometimes my camera will restructure the world for me, in ways I could never have foreseen. My optical decisions — using a view camera (indexing stillness, here deliberately unsettled) and a 35mm camera with a shutter drag — are intended to create conditions in which the photograph resists predetermination and positions film as a conduit for latency and delay. Might I evade totalising authorship by employing a (seeming) lens of ambivalence? Could that open up new narratives in the reading of presumably familiar images?

I think it necessary that the language of this work operate through modes of questioning — because that is how I arrived at the images; it is necessary, too, that the work remain open-ended.