The New Black West: Photographs from America's only Touring Black Rodeo

-

Dates2009 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Oakland, United States

-

Recognition

As long as there have been cowboys, there have been Black cowboys. This series shines light on Black cowboys whose traditions and mentorship programs transform lives, reshaping history and inspiring a more inclusive vision of the West.

It’s hard to imagine a more powerful symbol of self-reliance, strength, and determination than the cowboy. While the archetypal cowboy is a highly romanticized figure, and one that ignores ugly truths about the cost of westward expansion in the United States—namely the theft of Native American lives and land—still it has become synonymous with traits we almost universally admire. And while the archetypal cowboy is almost always depicted as white, in reality, no one better embodies these admirable traits than the Black cowboys who helped shape the culture of the American West. According to the late historian William Loren Katz, whose book tackles the whitewashed mythology of the American frontier, people of African descent “rode every wilderness trail—as scouts and pathfinders, slave runaways and fur trappers, missionaries and soldiers, schoolmarms and entrepreneurs, lawmen and members of Native American nations.”

Today, the resurgence of Western aesthetics in popular culture—most recently through Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter—has brought overdue attention to Black cowboy history. But beyond the fashion and spectacle, there are communities across the country carrying this tradition forward every day.

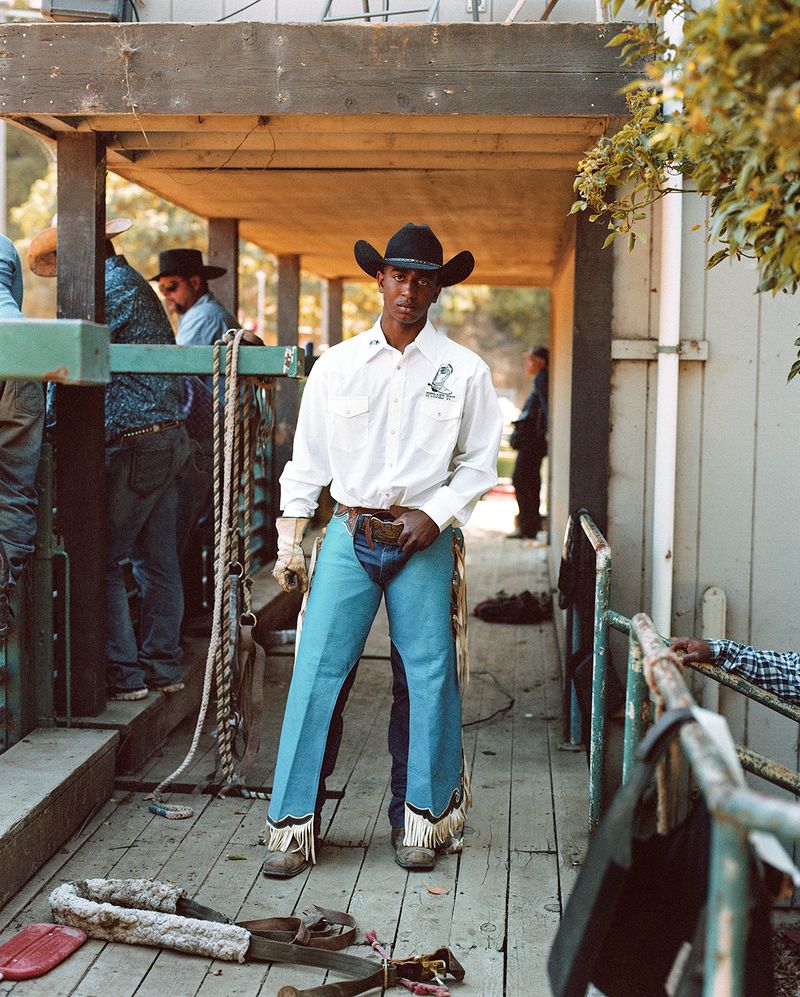

I have been documenting Black cowboys in the San Francisco Bay Area at the annual Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo since 2008. The families who return to the rodeo each year come to support one another and the other contestants. It’s a testament to their commitment not only to the sport but to their community. The bonds that are forged at the rodeo are undeniably strong. As cowboy Jamir Graham said to me recently, “My rodeo team is my family.”

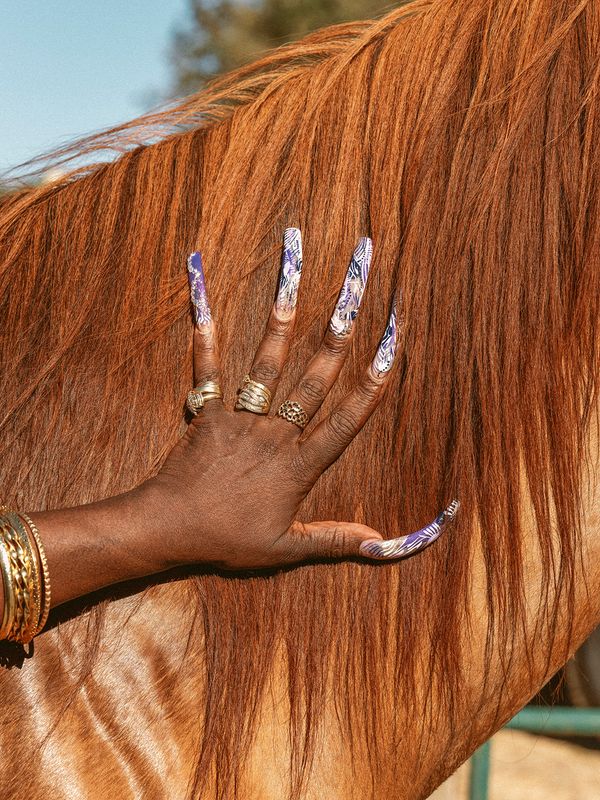

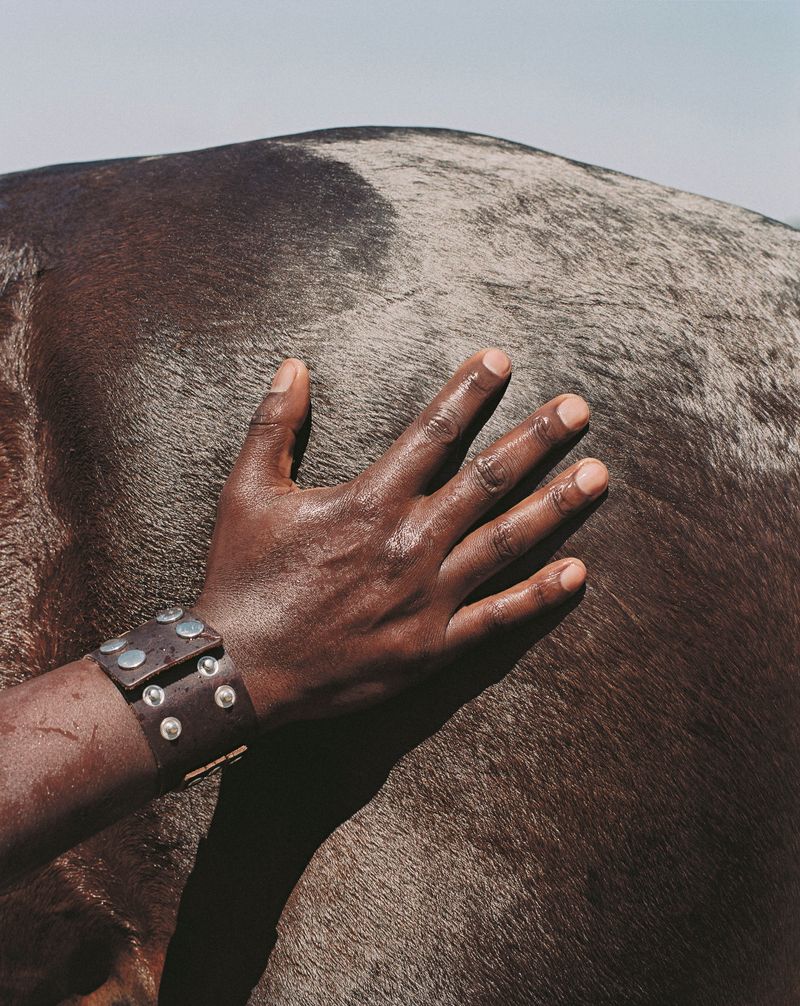

It was the intimate moments behind the scenes, the quiet time the riders share with their horses before a competition, and the relaxed atmosphere when the rodeo ended that lured me to document the contestants and the attendees many years ago. The beauty of the bonds they’ve formed—with the horses and with the other riders—continues to astound me. The intimacy, trust, and understanding are palpable both on and off camera.

The rodeo itself is named after a famous Black cowboy. The legendary Bill Pickett was the first Black rodeo athlete to be honored in the Rodeo Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City; he was inducted in 1971. The Miller Brothers recognized his talent in 1905 and hired Pickett to travel with them as a performer and exhibitionist in their 101 Ranch Wild West Show. Pickett was famous for grabbing a steer’s lip with his teeth—a feat known as bulldogging, as that is what bulldogs would do while herding steers—and became well-known for being a fearless and skilled rider. At the time, Pickett did not participate in the rodeos, as Black cowboys were not allowed to take part in the main rodeo and had to compete after the crowds had left. But at the Wild West Show, people from all over would come to admire his bulldogging and bull-steering skills as part of the show. The audience didn’t seem to care that Pickett was Black. They were enthralled by his talents.

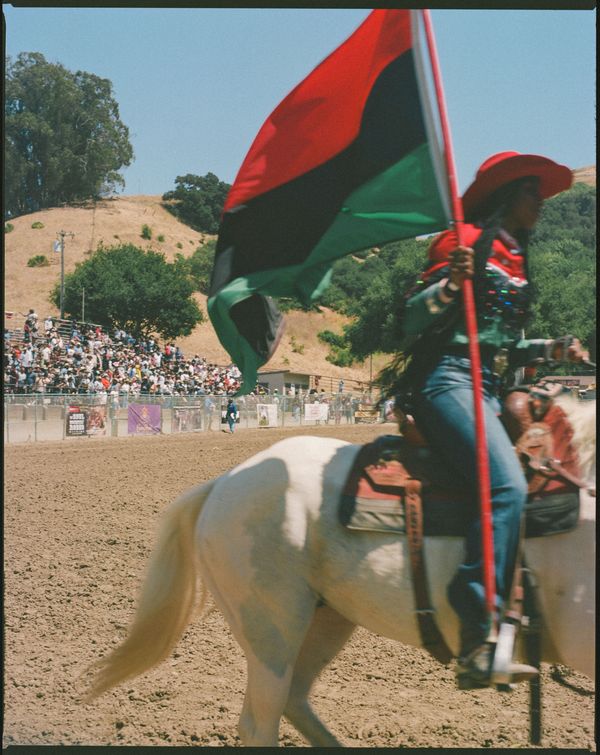

The Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo (BPIR) was founded in 1984 by Lu Vason, and to this day it remains the nation’s only touring Black rodeo. A hairstylist, concert producer, and promoter, Vason became interested in rodeos while attending the granddaddy of them all: the Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo in Wyoming. He quickly realized that there were no Black cowboys participating in that legendary production. On his return to Denver, where he resided in the 1980s, he began his research at the Black American West Museum, exploring the history of Black cowboys, the contributions of African American settlers, and the opening of the western frontier. After more than two years of research and fundraising, Vason produced the inaugural Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo in Denver, Colorado. This heritage rodeo helps educate people from all over the world about the rich history of Black cowboys and cowgirls, and it highlights their overlooked contributions to American rodeo culture.

The modern rodeo I’ve witnessed annually at Rowell Ranch Rodeo Park, just outside of Oakland, California, is a study in generational shifts. As young contestants enter this traditional competition, they bring with them new perspectives and styles. Gucci sunglasses and Stetson hats, cell phones and lassos, Louis Vuitton saddles and Wrangler jeans—it’s clear that something completely new is being forged in the collision of classic and contemporary. And not only are the riders inventing a new aesthetic, but they are exploring what it means to be a cowboy in contemporary America, in and out of the arena. Many cowboys and cowgirls believe the sport has saved their lives, and all of them recognize the intense discipline needed to keep and care for their horses. That discipline requires passion and commitment in equal measure.

Oakland native Brianna Noble explained, “I am really just so grateful that I could have such a positive addiction, because I really think that horses are actually, truly a drug and addiction in the most positive sense of it, you know. They really have kept me on the straight and narrow throughout my life and taught me an unmatched work ethic, and really just kept me into all the positive things in my life.”

The people who gather annually for the rodeo make up one of the most lively, bighearted, kind, and compassionate communities in the Bay Area. Many cowboys and cowgirls also run year-round youth programs—Brianna Noble’s Mulatto Meadows, Sam Styles’s Horses with Styles, and the Spurred Up program, for example—that offer inner-city kids the opportunity to work with horses as a form of therapy. “I’m always looking for the next thing to help these kids. I’m looking for the next way to get another kid here,” said Styles of his youth program. “Riding is not for everybody. And I know I can’t save every single life. But if I could get one more kid here and keep them off the streets of Oakland, or be able to get them away from what they’re going through at home, in a troubled situation—I mean that’s just one more kid who could have a different outlook on life.”

For decades, these urban cowboys have found joy in the traditions passed down by their predecessors. I have gotten to know many of those who participate in the rodeo, most of whom have a strong network of friendships in the Bay Area. Throughout my twelve years of attending the rodeo, my friendship with the cowboys has brought me closer to their communities and families. They have invited me to their ranches to see them ride and care for their horses outside the arena. I’ve taken hundreds of pictures over the past decade that document the talent, dedication, and love of this community. It’s a dream come true to share their passion and skill with the rest of the world.