I Still Do Not Know Him

-

Dates2022 - 2024

-

Author

- Locations Tokyo, Sichuan

-

Recognition

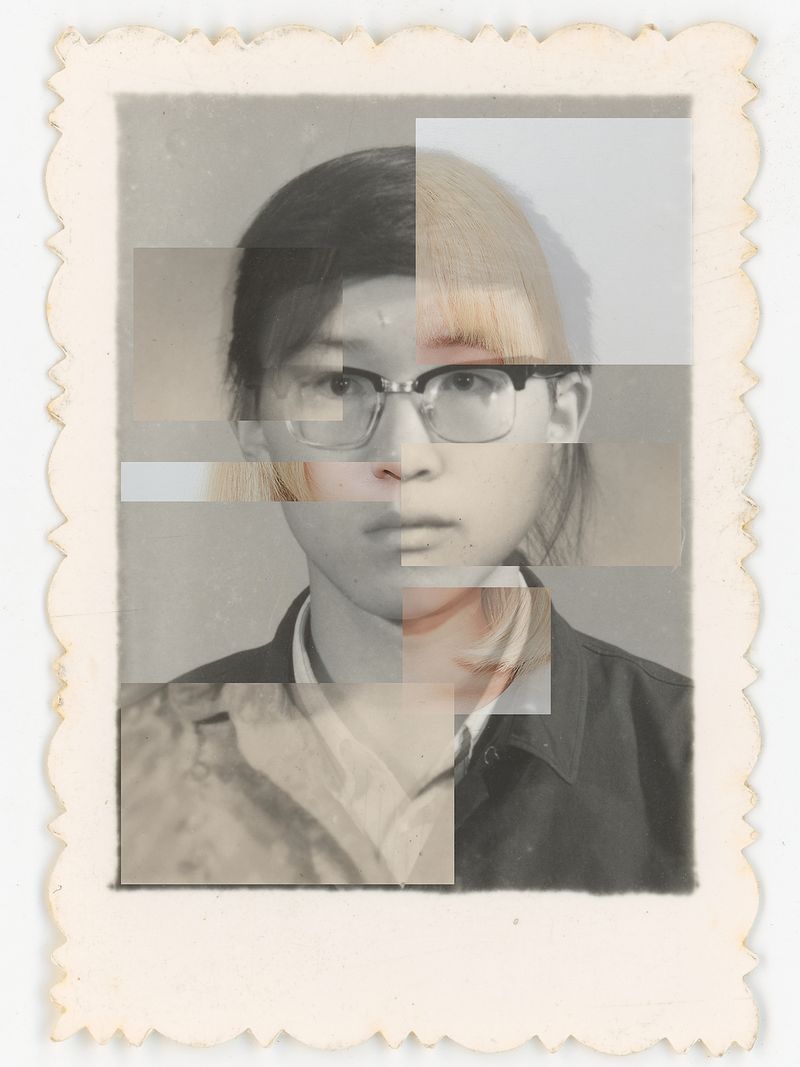

Against the backdrop of China’s One-Child Policy, this project explores a family shaped by state control and local beliefs. Through photography, I give form to an absent older brother who exists only in spiritual and emotional memory.

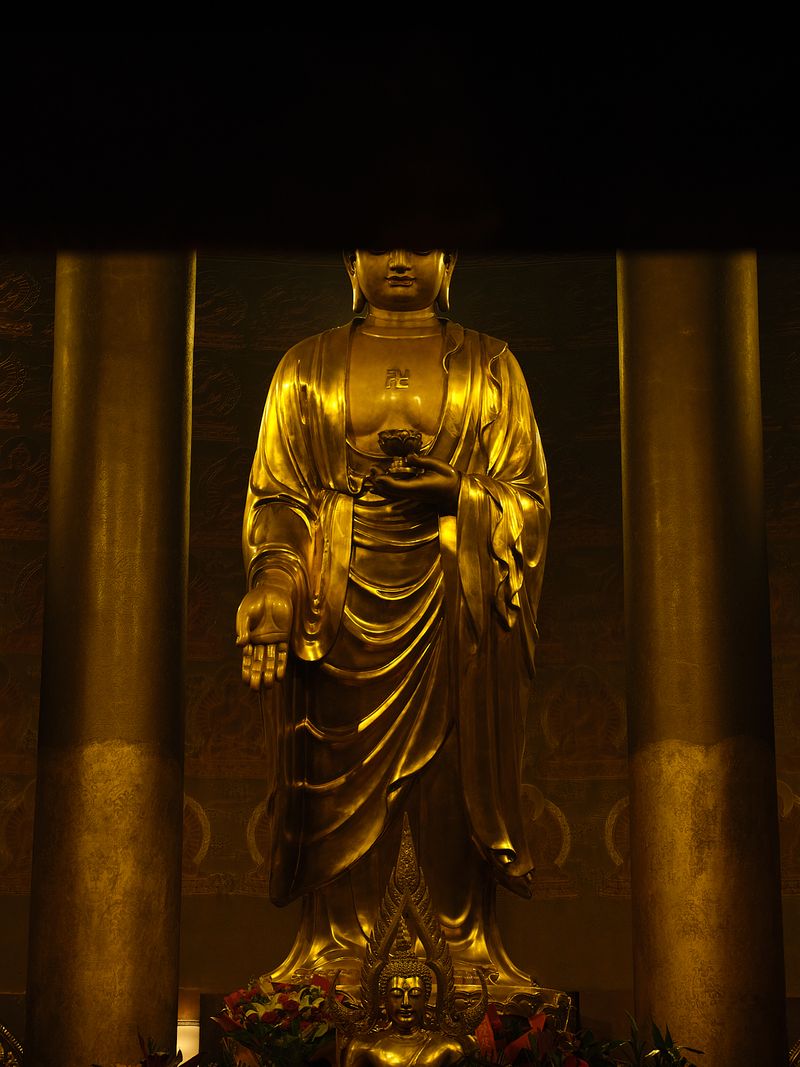

During China’s One-Child Policy era, my mother was pregnant with another child before me, but the baby was stillborn. According to local folklore, a child who dies in the womb is believed to be a temporary spiritual visitor, repaying karmic debt before returning to the Buddha’s side. My mother believes in this legend and often visits temples to pray for that lost child.

As a child, I sometimes imagined having a brother, but now I realize that if he had been born, I probably wouldn’t exist. Through photography, I seek to represent this absent sibling—someone who both exists and does not exist in our family’s narrative. I photograph spaces and symbols that evoke his intangible presence and the silence that surrounds it.

The project is rooted in my personal history, yet it reflects a broader generational experience shaped by national policy and regional beliefs. As someone born under the One-Child Policy, I explore the tension between “presence” and “absence,” and how policy, memory, and belief systems shape our understanding of family. With the policy’s end in 2016, the era of only children quietly submerged like stones in a river. By tracing the invisible marks of a brother who never lived, this work confronts the social and institutional scars left behind and attempts to visualize what cannot be seen.

About the One-Child Policy

On December 29, 1978, the Chinese government enacted the Population and Planned Birth Law of the People's Republic of China to control population, and officially implemented the One-Child Policy on September 1, 1979. The implementation of the One-Child Policy was accompanied by a declining birthrate and aging population, which led to labor shortages and shrinking domestic investment and consumption. As a countermeasure, in January 2016, the "two-child policy" was fully implemented, allowing all couples to have a second child, and the one-child policy, which had suppressed population growth for 36 years, came to an end and was buried in history. Furthermore, in 2021, when deregulation accelerated, the Chinese government amended the Population and Planned Parenthood Law to allow all couples to have a third child.

Behind the repeated policy changes, however, is a rapidly declining birth rate. We believe that one of the reasons for this is the view of the family and social perceptions that took root during the one-child policy era. Although the one-child policy has ended, this does not mean that one-children have disappeared, and problems related to one-children still exist even after the one-child policy era. The reason is that the one-child policy, which lasted for nearly 40 years, made the three-parent family the typical family structure in China, and the "late marriage," "late childbearing," "fewer children," and "eugenics" (meaning "nurturing human resources") advocated by the one-child policy have become common knowledge among the people. In addition, the educational problems of an only child, the problems of caring for an only child's parents, the lack of kinship, and the social impact of the one-child culture are social problems that will exist for a long time to come.