Zagara—Ogni fiore porta il profumo del suo segreto

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Sicily, Italy

«Zagara—Ogni fiore porta il profumo del suo segreto» reflects on intergenerational memory, exploring how unspoken histories of violence and resilience continue to shape women’s lives in Italy today.

Project Description

«Zagara—Ogni fiore porta il profumo del suo segreto» is a visual investigation that reclaims matrilineal memory as both resistance and reparation.

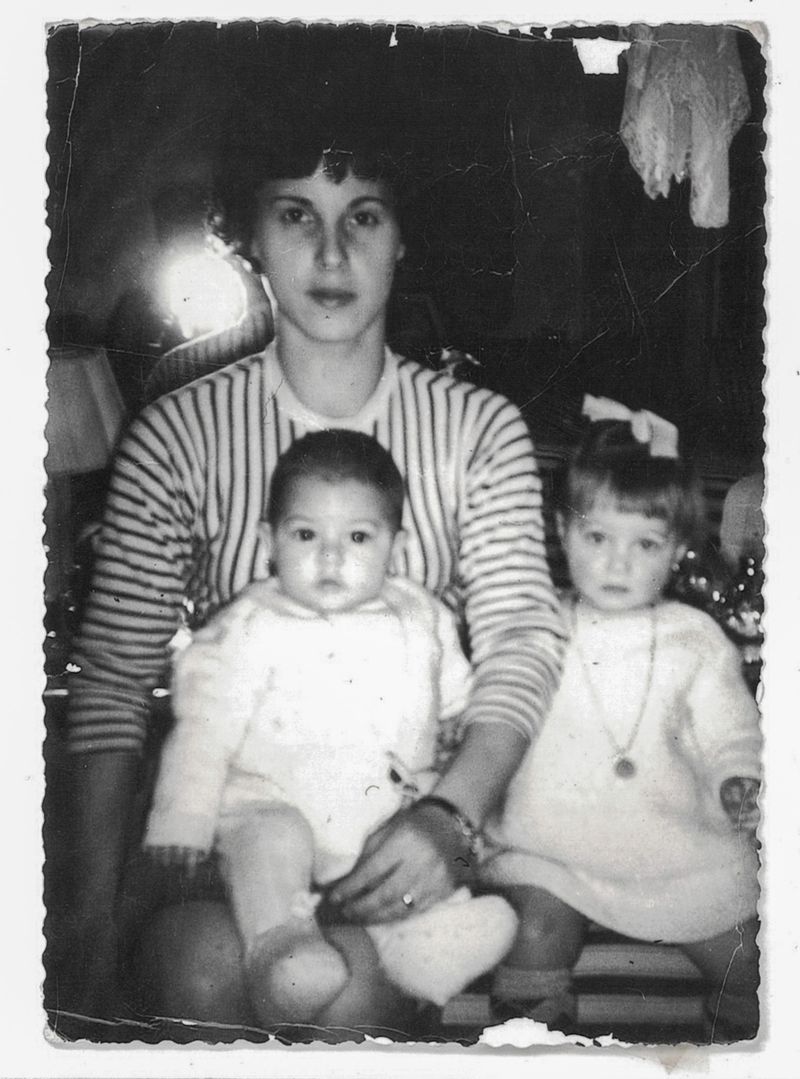

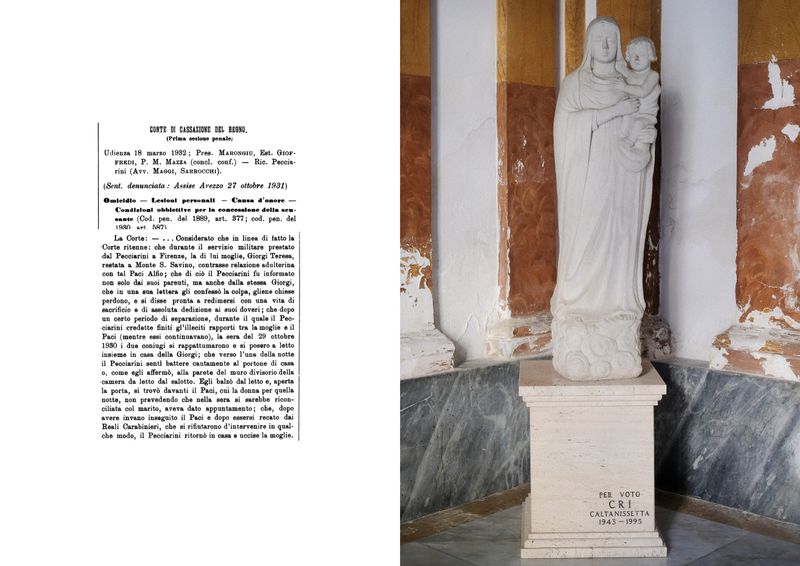

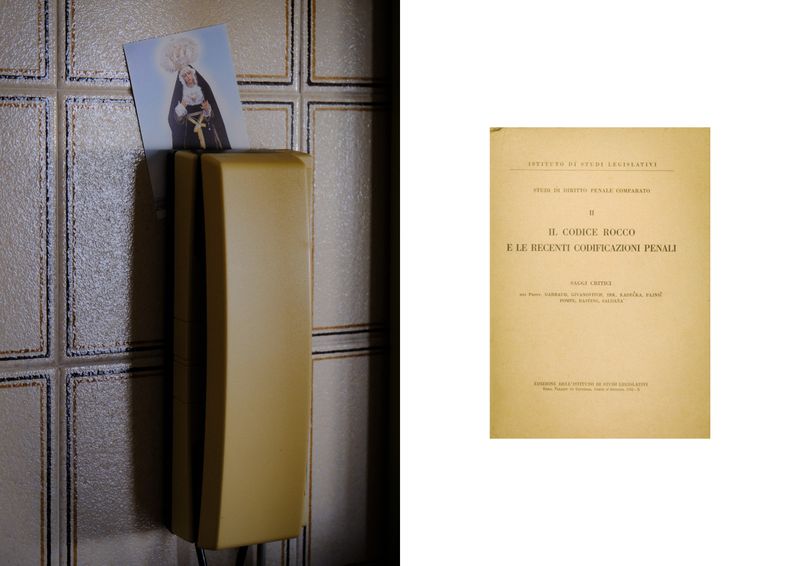

It emerges from the story of my great-grandmother, who escaped an attempted femicide in Sicily in 1939, at a time when the Codice Rocco still legitimized such crimes in the name of "honor". The project explores how gender-based violence leaves lasting traces not only in the body, but also in silence, gestures, and inherited emotional landscapes.

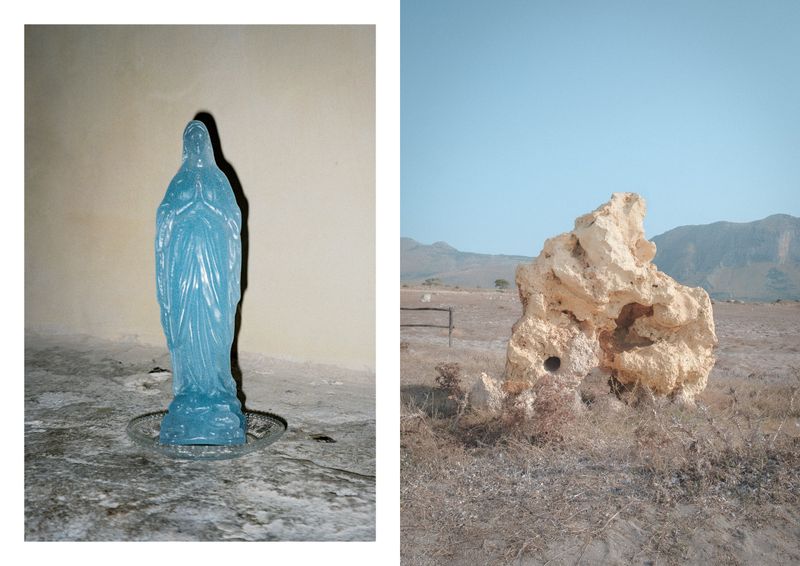

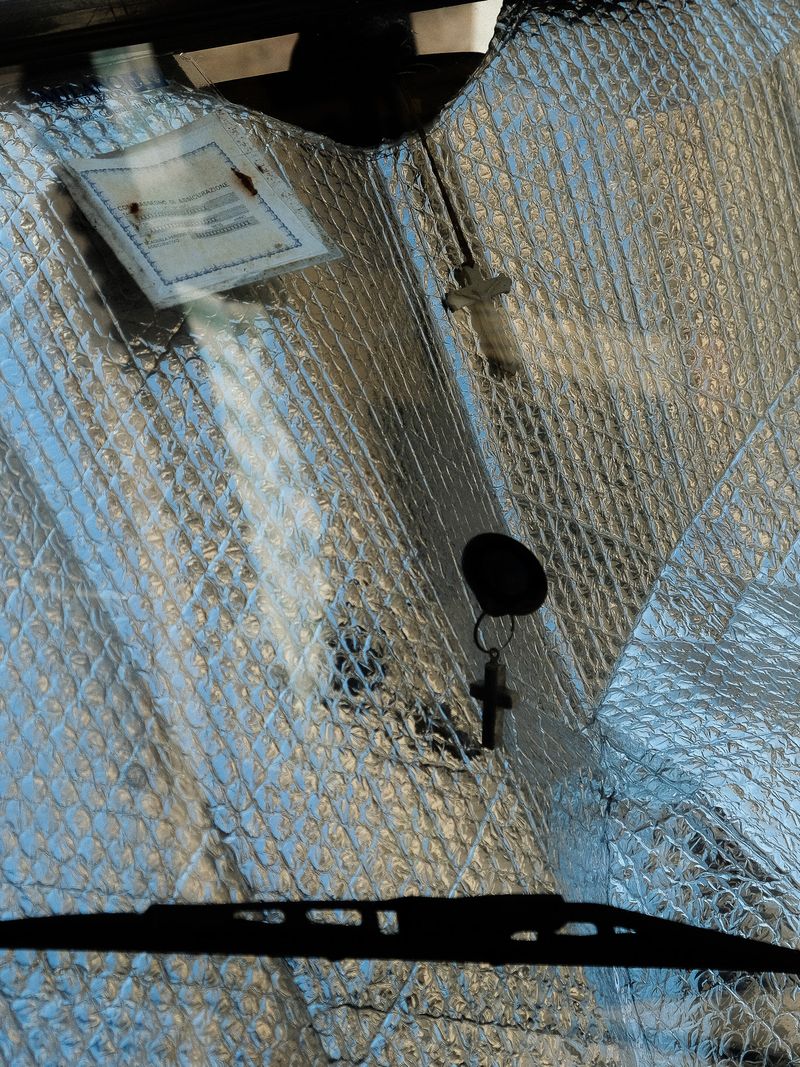

At its core, the work reimagines the family archive not as passive memory, but as an active, contested site, where histories can be rewritten, silences broken, and erased voices re-centered. Engaging with these materials becomes both personal and political: an act of reclamation against systems that have long controlled how women’s lives are told, remembered, or forgotten. The symbolism of zagara (engl. orange blossom) threads through the project as a sensorial metaphor. Traditionally tied to love, marriage, and purity, its fragrance here embodies contradiction: affection bound to duty, and beauty used to enforce control. What is meant to sanctify can also suffocate.

Although rooted in personal history, the projects gestures toward a broader emotional landscape, shaped by quiet inheritances and unspoken systems that extend beyond place or generation. By linking family history with collective memory, it highlights how gender-based violence persists across generations, even after legal reforms. Until 1981, Italian law still reduced sentences for men who killed wives, daughters, or sisters "to defend family honor." That legal framework may be abolished, but its cultural afterlife endures — in the silences within families, in Catholic archetypes of Madonna and Magdalene, and in media narratives that continue to frame femicides as "crimes of passion."

The present project honours the women who came before me not only for their resilience, but for the emotional labour they carried without recognition. It also acknowledges how certain forms of violence persist, not always visible, not always named, but deeply embedded in the fabric of everyday life. Rather than offering resolution, the work holds space for complexity. It moves through memory not to reconstruct a linear story, but to listen differently: to what resists clarity, to what persists.

Ultimately, «Zagara—Ogni fiore porta il profumo del suo segreto» is not only a work of remembrance but a visual protest. It confronts structures that define, constrain, and erase women, while reclaiming photography as a practice of care and resistance. By intervening in archives and opening space for new voices, it asks how memory can become a tool of both survival and transformation.

[The captions take the form of my field notes — fragments of inner dialogue, questions, and encounters that shaped the work. They weave together personal anecdotes, obstacles faced as a woman, and reflections from conversations or research, from family silences to legal philosophy. In this way, they position me inside the project, acknowledging that inquiry is never neutral but entangled with memory, vulnerability, and discovery.]

Motivational Statement

My background in law shapes the way I work with photography: as a field where power, memory, and representation collide. Laws may be reformed, but their afterlives remain present — in culture, in language, in the ways women are still seen and judged. Through this work, I ask how those traces can be confronted and reimagined visually.

With this work, I want to expand a deeply personal starting point into a broader inquiry on how gender-based violence is remembered and represented, in Italy and beyond. It is both an act of care and a form of resistance — holding space for complexity, while questioning the narratives that continue to constrain women’s lives.

The PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant would would not only support the ongoing development of the project, including further archival and field research, but would also allow me to strengthen this dialogue internationally — to bring the work into new contexts of exhibition, exchange, and visibility. What motivates me most is the possibility that a story once silenced can contribute to a collective conversation, amplifying voices that risk being erased.