You Are My One And Only

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Archive, Awards, Contemporary Issues, Daily Life, Documentary, Editorial, Festivals, Fine Art, Photobooks, Portrait, Social Issues, Studio

- Location Burnham, United Kingdom

A house, a home, a heartache.

What my parents didn’t know when they started a family was that they were both carriers of an ultra-rare and fatal genetic condition called Pompe Disease.

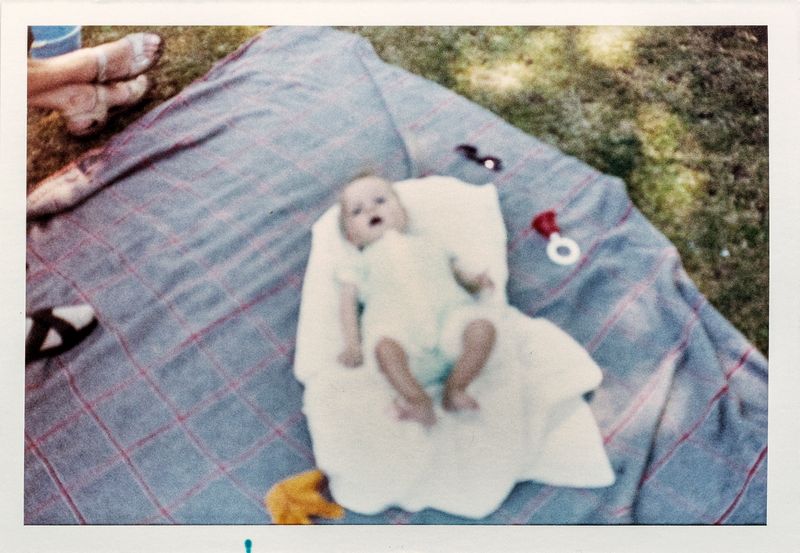

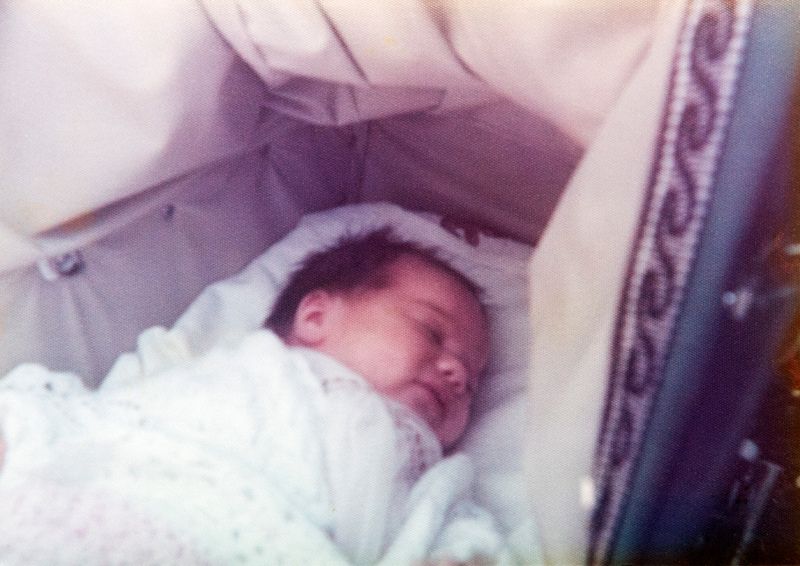

I am their eldest, and only, surviving child. I was born in 1970, and my genes are totally unaffected. Mum and dad had one faulty gene each - a missing enzyme on Chromosome 17. In the lottery of genetics my younger brother and sister inherited both sets of faulty genes.

My brother Rupert was born in 1973 and died later that year. My sister Caroline was born in 1974 and died in 1975. Both were under a year old. It is difficult to know the exact number of people with Pompe worldwide. Historical estimates based on genetic data suggest Pompe Disease incidence could be somewhere around 1 in 40,000 people.

Among my earliest memories are the day my brother died, being told about my sister’s death and then the day of her funeral. Eventually, we became a close family of three. Somehow my parents got through, but grief always remained in our house.

Over the years, mum would say to me: “You are my one and only”. As I grew up, I began to feel that this was more than just an expression of a mother’s love for her son. Wrapped up within it were other layers of loss, grief and sorrow. It was a phrase that came to sum up both my mum's pain and the burden of being the surviving child.

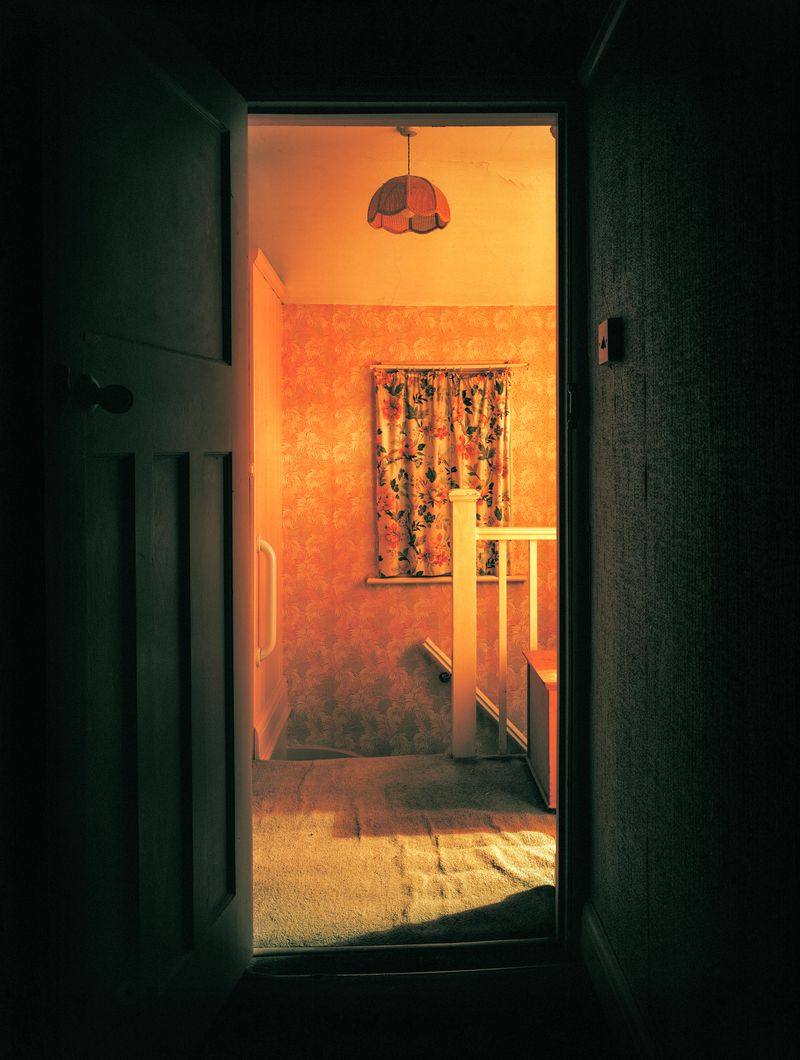

Dad died just before Christmas 2020, a little over three years after mum. Now I had the task of clearing the family home that my parents had moved into in 1967 and had never left. For years I had wanted to tell the story of my siblings, but I didn’t know how to begin. Until now. I realised that the house and its contents could be both a vehicle and a metaphor to explore what I was feeling.

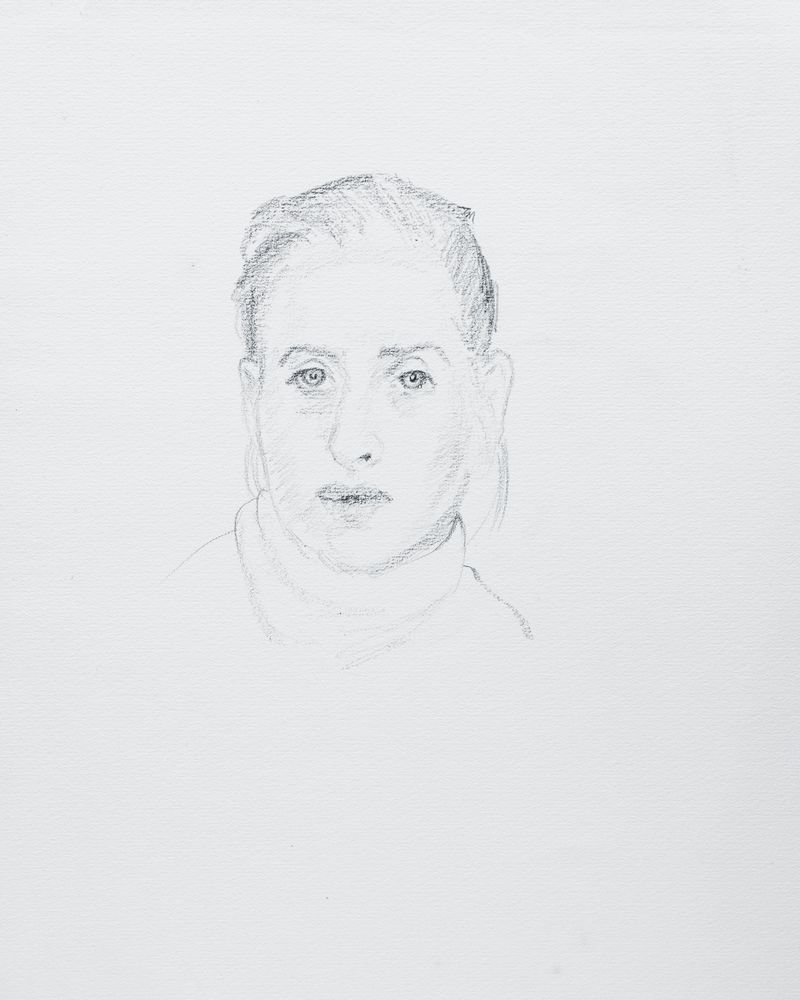

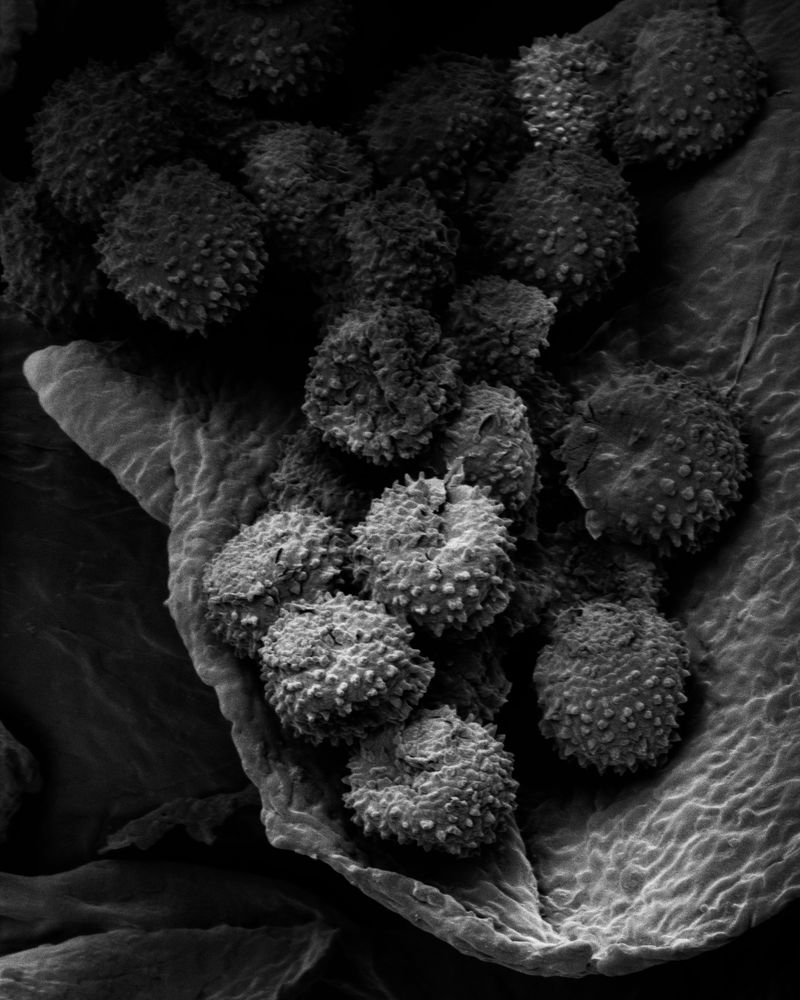

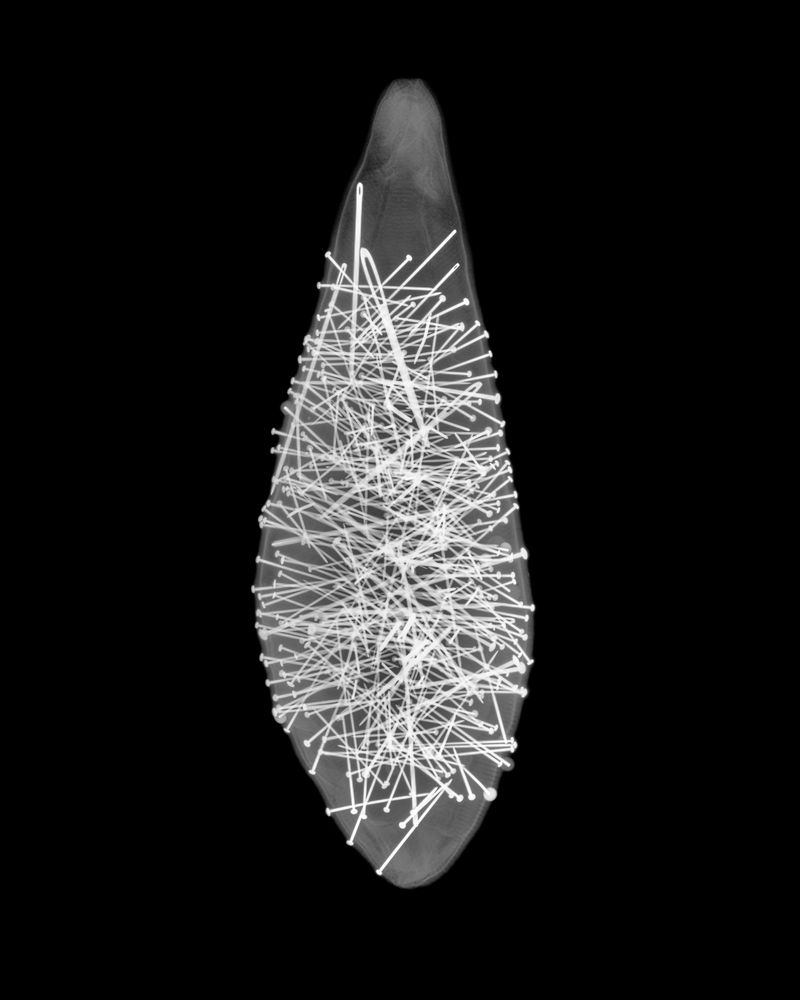

I photographed everything in the house: the clutter, the objects, the papers, the spaces, the dirt, the light. My approach was emotionally forensic, and I felt like an archaeologist peeling back the layers of a deeply held family story. A medical aspect to the images was also important because of genetics. I found objects with hidden inner spaces and got them x-rayed - like mum’s pin cushion, to see where all the pins went. Then I bagged up the dust and took it to the University of Cambridge to reveal its hidden inner worlds using an electron microscope.

I have mixed my own images with those from my family archives. I have wanted to examine the past and the present, to look at the detail of each surface and to see through spaces, objects and above all time - as if everything has its own DNA. I have needed to find pictures for events and things where there are no pictures, and to show what is missing and what remains. It has been a strange form of inheritance.