*to die is to be turned to gold

-

Dates2022 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Mumbai, India

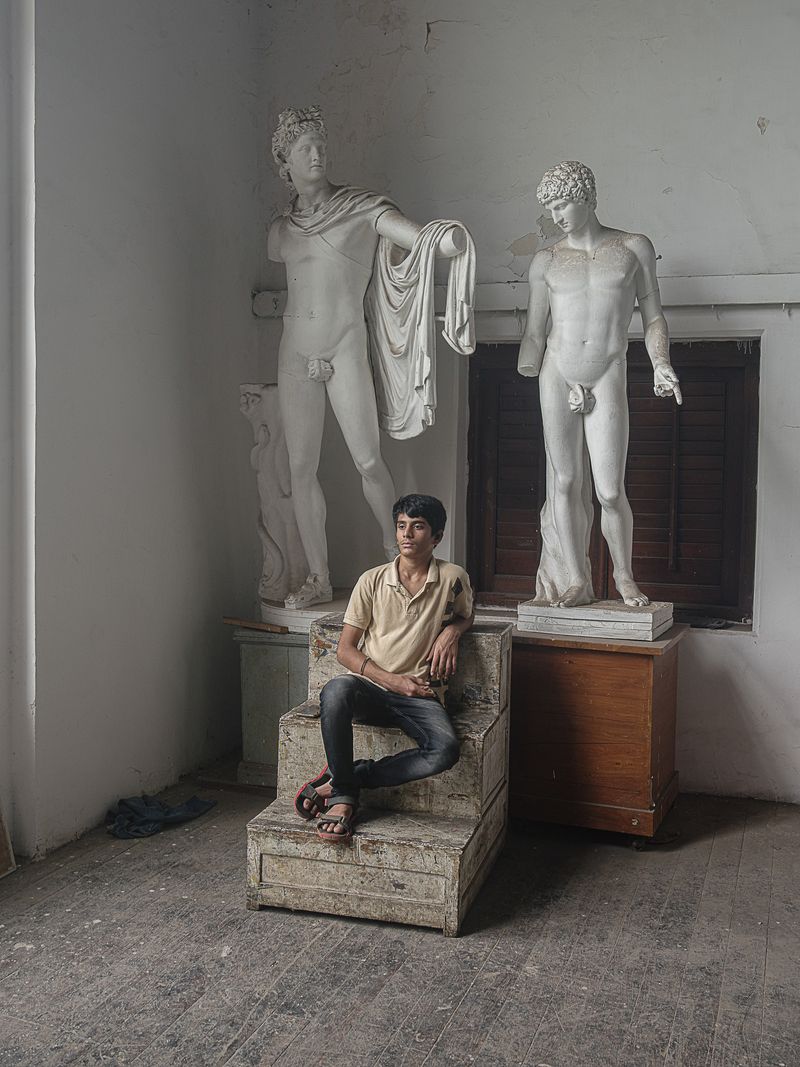

In his portraits, street photographs, and still lifes, Mahajan envisions Mumbai through the eyes of a sculptor who walks the city in search of a muse.

To Die Is to Be Turned to Gold is an in-progress body of work that returns to the once-colonial city of Bombay (now Mumbai) and tries to read it from the ground up — through the eyes of a protagonist: a young sculptor of commercial statues. The city is their quarry and their classroom. For over three hundred years, people have arrived here hoping to make their fortune; many have died in that pursuit. Their bodies were laid in a place known as Sonapur — “the city of gold” — echoing an Indian saying: to die is to be turned to gold — a cruel consolation, suggesting that even when dreams collapse, the city rewards its dead. Here, gold is not wealth but residue: what remains when lives spent in pursuit of fortune are absorbed back into the streets. Hence the city’s other name — the City of Dreams.

Bombay and Mumbai exist side by side in the work, not as a simple before and after, but as overlapping inscriptions. Each name carries its own histories, aspirations, and erasures. The city is repeatedly rewritten — through renaming, redevelopment, demolition, and repair — and these acts of revision leave traces in its buildings, its monuments, and its images. The work lingers in this unstable space, where the past is not replaced so much as layered, edited, and repurposed.

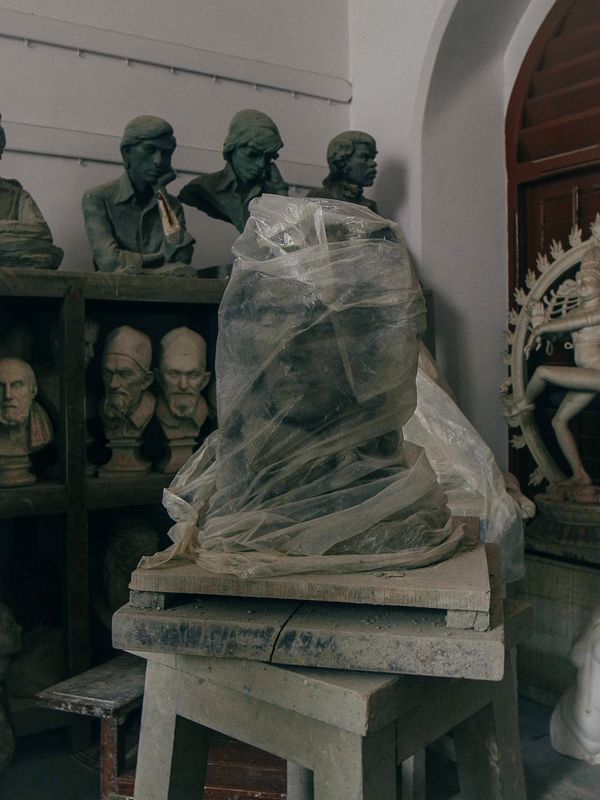

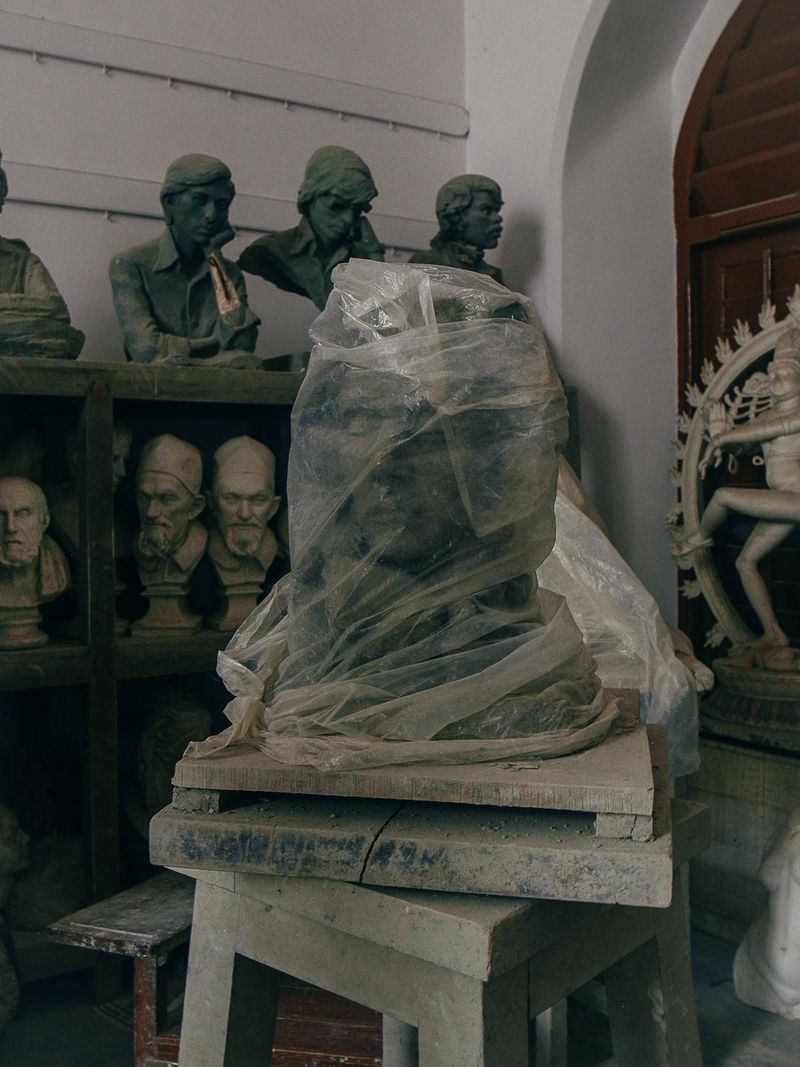

The sculptor’s practice becomes a way of thinking about how the city manufactures likeness and belief. They look at people the way one studies material: patiently, attentively, with an eye for surface, proportion, and pressure. Sitting in cafés, watching faces pass, they carry images home. In the studio, bodies are assembled from fragments — a nose borrowed from one person, ears from another — composite figures shaped as much by feeling as by form. This method mirrors the city’s own logic: identities pieced together, renamed, and fixed into recognisable types. If empire once sculpted the city through monuments and categories, these composite bodies misbehave with permanence, refusing a single, authoritative face.

The camera follows this sculptural gaze. The photographs move between street scenes, portraits, landscapes, and close-up details, tracing a city whose surfaces are never only surfaces. Architecture appears as a second kind of statue — both formal and vernacular structures read as sculptural records of failed futures. In the old financial centre, forsaken relics of late-1950s Nehruvian functionalism linger as props from an earlier promise. Elsewhere, corrugated tin, plywood, plastic, asbestos sheets, earth, sand, and clay accumulate into the improvised dwellings of millions — structures built from what the city discards, yet carrying a stubborn intelligence of survival. Colonial buildings are rarely dismantled; instead, they are renamed and repurposed, reappearing as contemporary institutions of finance and power.

Running through the series is a sustained attention to public representation — statues, monuments, façades, official images — and to the labour that produces them. Figures recur, gestures repeat, forms echo earlier forms. An equestrian statue riding toward the Arabian Sea cannot help but summon an older equestrian king; one monument replaces another, history revised through substitution rather than reckoning. The city quotes itself endlessly, smoothing over rupture while leaving its scars visible to those who know how to look.

To Die Is to Be Turned to Gold is less a portrait of Bombay or Mumbai than an inquiry into how the city continually remakes itself through acts of naming, building, and representation. The work unfolds as a visual performance, meant to be read the way one reads a building: not as a stable object, but as a structure that records time, labour, and desire. Between statue and body, between gold as promise and gold as residue, the work stays with what remains unresolved — and with the ghosts that persist when a city insists on moving forward.