The sea is rough

-

Dates2021 - 2022

-

Author

- Locations Russia, Ural

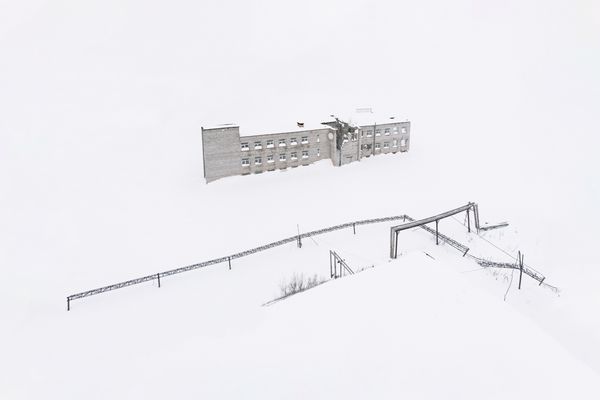

The impetus for this project was a technological disaster in my hometown, Berezniki, in the Urals. The city was built in Soviet times atop a field of potash salts left by the ancient Perm Sea, and nearly the entire town stands above the mines. One day, groundwater began to seep into the shafts and dissolve the salt. The walls of the mines began to collapse, and the city began to follow. Huge sinkholes—sometimes filled with water—opened across the city and its outskirts. In the schoolyard where I used to play as a child, there is now a hole in the ground. Because of the sinkholes and crustal movement, part of the city was declared an emergency zone. The railway also collapsed; trains to Berezniki no longer run. Cracks appeared in many buildings. People are being relocated, houses are being demolished—slowly, the city is being covered by empty spaces.

I see in this catastrophe both nature’s reply and stark, powerful poetry. The earth dissolved the salt with the help of groundwater, and it is as if the ancient sea had awakened, grown angry, and decided to put humans in their place. I became interested in the history of the ancient Perm Sea and began to study the territory where it once lay. What I encountered along the way, during this journey across what used to be the bottom of the ancient Perm Sea, looked different from place to place, yet in essence it was not so different from what had happened in my hometown: people dug, blasted, exploited, and took everything they could take.

I took the last photographs for this project in January 2022. I didn’t know then that they would be the last. In February 2022, I had to emigrate. Today, looking at these photographs, I see my homeland sinking into the abyss, and also the home I left behind, which in my memory has turned into a frozen crystal of bitter salt.