The Keys to the Factory

-

Dates2022 - Ongoing

-

Author

These experiments were enabled by my personal background: my family owns a printing factory in the Lyon region, which has been passed down four generations. The importance of this space was heightened by it becoming the very subject of my photographs.

INTERVIEW BY SALOME BURSTEIN

Motor systems, office desks, storage rooms, paper wastes…This new series focuses on the uneventful, on things we don’t care to notice. How familiar they might initially be, these objects are estranged, distorted, made unrecognizable – requiring a perceptive effort from the viewer to decipher what is represented. Could you tell us a little more about your process? What do those formal experimentations speak for?

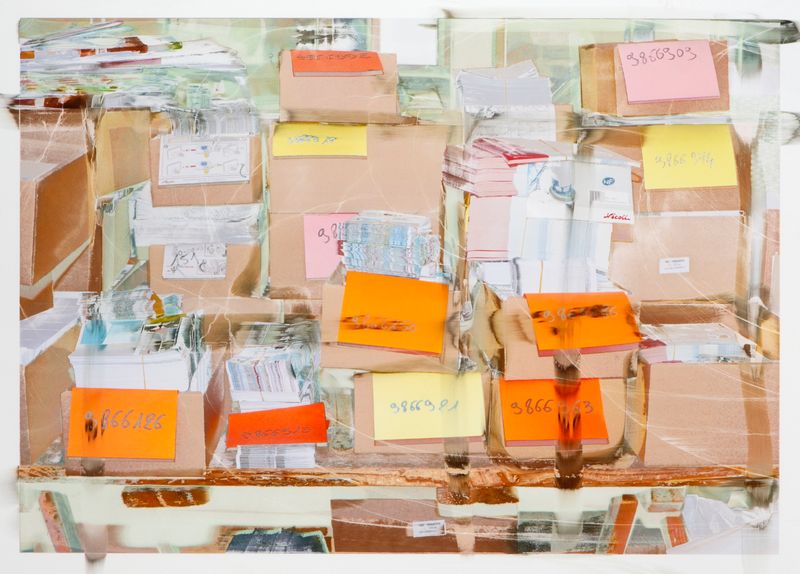

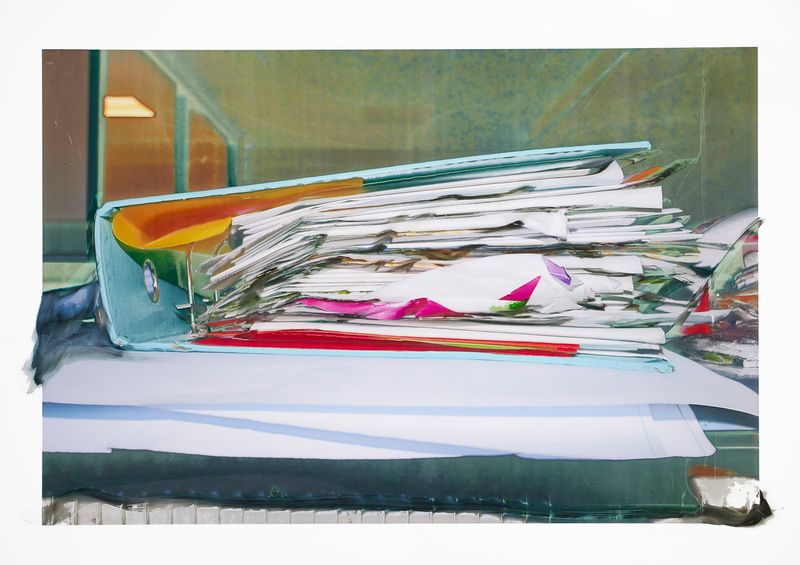

Whether analog or digital, my photographs are scanned or de-rushed before being printed on fiberless, waterproof, thick plastic materials commonly used in offset lithography. Here, the ink is projected out of the machine onto the paper roll without completely being embedded in it. When obtained, the image is in an inchoative state: it is still alive, moving, somewhat organic. It’s also extremely sensitive to touch. I started playing around with this breathing material; I was curious to see how I could still be involved in its life cycle. From coating or sweeping to blow drying, I investigated a wide range of techniques, all of which produce specific and peculiar effects. These experiments were enabled by my personal background: my family owns a printing factory in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, which has been passed down four generations. Thanks to this, I had access to the resources these tryouts required. I also felt comfortable handling the machines, messing around with them, tormenting them a little at times; they were familiar tools I already shared some sort of intimacy with. This importance of this space was heightened by it becoming the very subject of my photographs. I started documenting the factory, but rather than photographing its workers – in this case, my family members – I focused on the horde of engines, details and non-human entities populating this industrial organism. From the graphic designers’ office desks to the outdoor delivery system, I wanted to show the physical spaces through which images transit; where they are produced and disseminated, following the rhythm of daily orders. The angle and lens left aside, nothing in this series is staged: what we have is the location in its most neutral form, stripped-down, bare-naked.

This series could therefore be understood as inquiring the spaces and ways images circulate, the labor attached to their production and – consequently – what they might be worth. This is hinted at by its title, which ironically contrasts with the prosaicness of the elements you chose to portray: Heirloom. Overall, it seems like the notion of value underlies this work – not only in its economic dimension, but also in the affective sense. How does sentimentality permeate this project?

I guess it crystallizes in the conflicting relationship I have to the factory. This space has been part of my childhood and upbringing. It is where I grew up, where I got my first job as a teenager to earn pocket money etc. I used to hate everything about it: its early-morning working hours, its smell, the ink-stains it left on my father's hands… It constituted an environment I gladly left behind when starting my studies – a way of saying I would promise myself to another future, different from that of my elders. It took me years to come back to it with positive feelings. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that it happened only after having completed my education and with the purpose of developing an artistic project: last summer, I used the three weeks of the factory’s annual closure to create Waterworks, 30 unique artist books published by RVB and all printed by hand. Since then, I have been investing the building in its non-operating hours – when it is asleep and deserted; when I can have my own relationship to it. Bit by bit, I became fascinated with the space and initiated some sort of autobiographical journey through it: I tried to map out the people who had worked there, asked my grandfather for any archive he might have kept… This factory, which no family member intends to take over today, is what is known as a "commercial printing house". In other words, it is not used for artists' prints or books. At the core of its business is poor material: cheese labels, town hall flyers, porn DVD blisters etc. Paper made not to be preserved, but to be recycled. To use the space as I did – working with its resources, capturing its image – implied to make it deviate from its traditional function. And it was undoubtedly a way of situating myself within this lineage, of twisting this heritage to occupy a position I feel is my own.