The bride in the maze

-

Dates2023 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Palestine, Palestine

The work explores the psychogeography of the West Bank, challenging dominant narratives and offering a fragmented yet intimate portrayal of Palestinian life. Through evocative imagery, it reframes perceptions of apartheid and resilience.

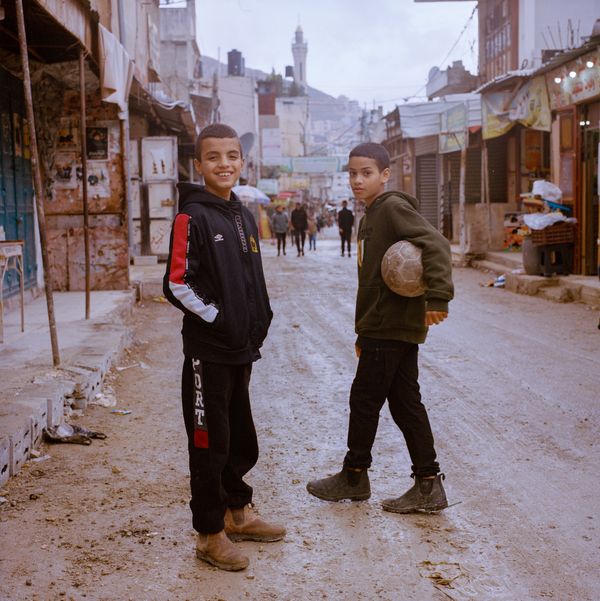

This work is born from walking through the streets of the West Bank, from watching the children play between rubble and checkpoints, from listening to the stories of those who have known nothing but the walls that enclose them. It is an attempt to trace the psychogeography of Palestinian life under occupation, to understand what it means to grow up in a land that is both home and a maze of barriers, watchtowers, and ever-present tension.

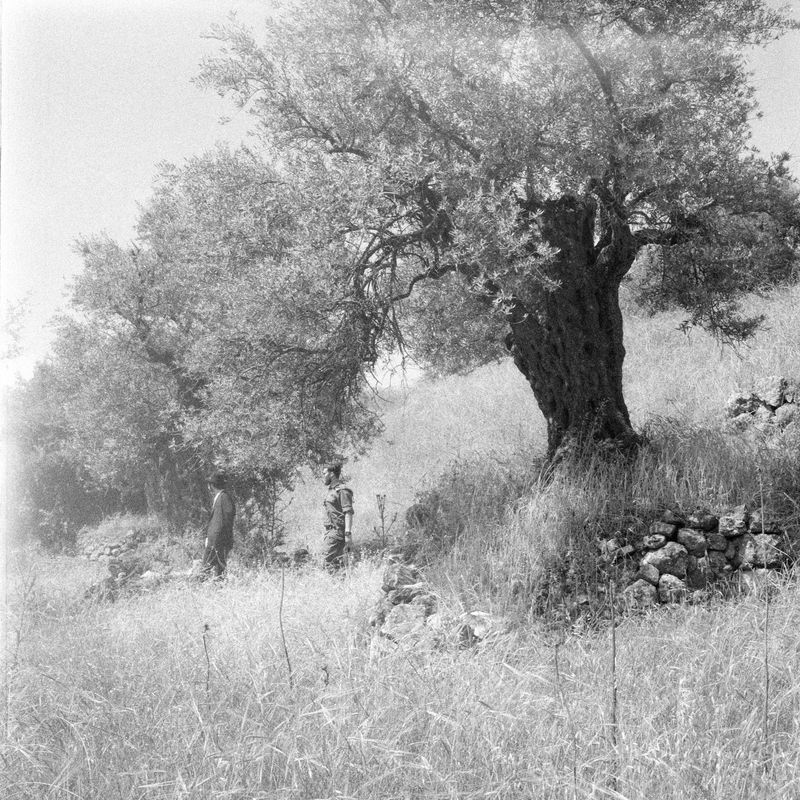

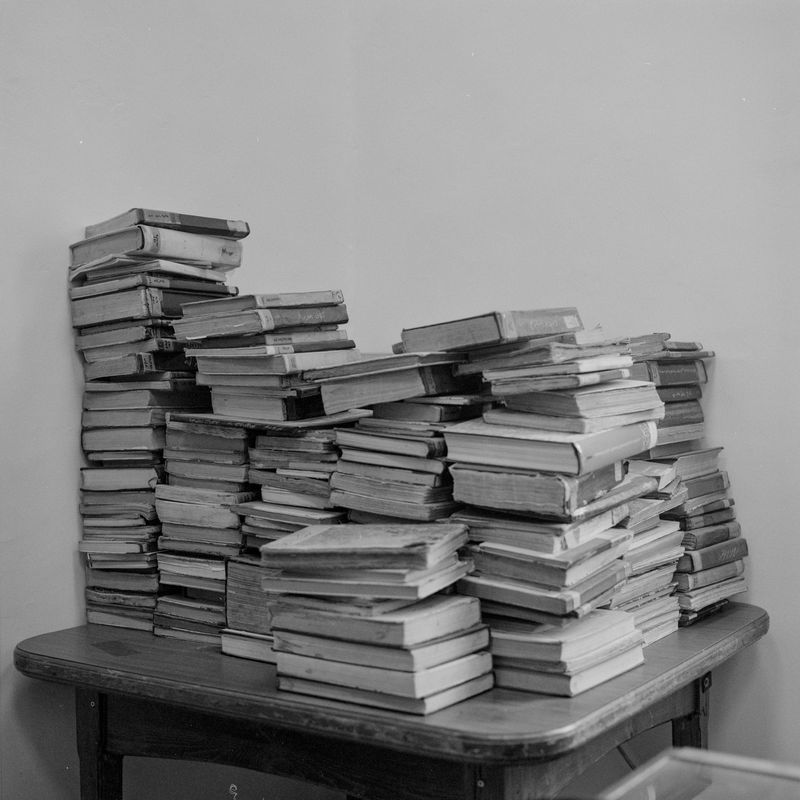

Through a series of images and narratives, the work reveals the power structures that define life in this space. The children kicking a deflated football in the shadow of a 700-kilometer wall. A young girl practicing Jiu Jitsu, her fist raised in quiet defiance against the occupation. A demolished school, a bulldozed Mosque. Settlers armed as they claim more land. These fragments form an intricate and shattered mosaic, one that Western media often chooses to ignore. And yet, what emerges from this maze is not just loss and oppression but resilience, dignity, and an unbreakable bond between the people and their land.

The title refers to the phrase “The bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man”, allegedly spoken by British Zionists in the 19th century as they surveyed Palestine. They saw the land, rich in history and culture, and understood that it already belonged to a people with deep roots. This phrase becomes a starting point for questioning the Western narrative surrounding the creation of the State of Israel—a narrative that has often been framed through a lens of propaganda, obscuring the colonial nature of the project.

The maze in this work is both literal and metaphorical. It is the architecture of apartheid—checkpoints, segregated roads, walls, and fences that confine Palestinians to ever-shrinking enclaves. But it is also the cyclical nature of history, where the roles of persecutors and persecuted shift, yet the machinery of segregation, ethnic cleansing, and displacement remains unchanged. To walk through this maze is to understand the weight of history repeating itself, the feeling of moving in circles while the world looks away. And yet, through it all, life persists. Children still laugh. A young girl still trains. A people still resist, not just with protest but with the simple, radical act of continuing to exist.