My Dad Lives On The Moon

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Orania, South Africa

I’m left unresolved. My dad lives on the moon is a work about a daughter seeking to understand, but also about South Africa’s unfinished reckoning with peace and belonging - the quiet, unresolved spaces that endure between people, love and exclusion.

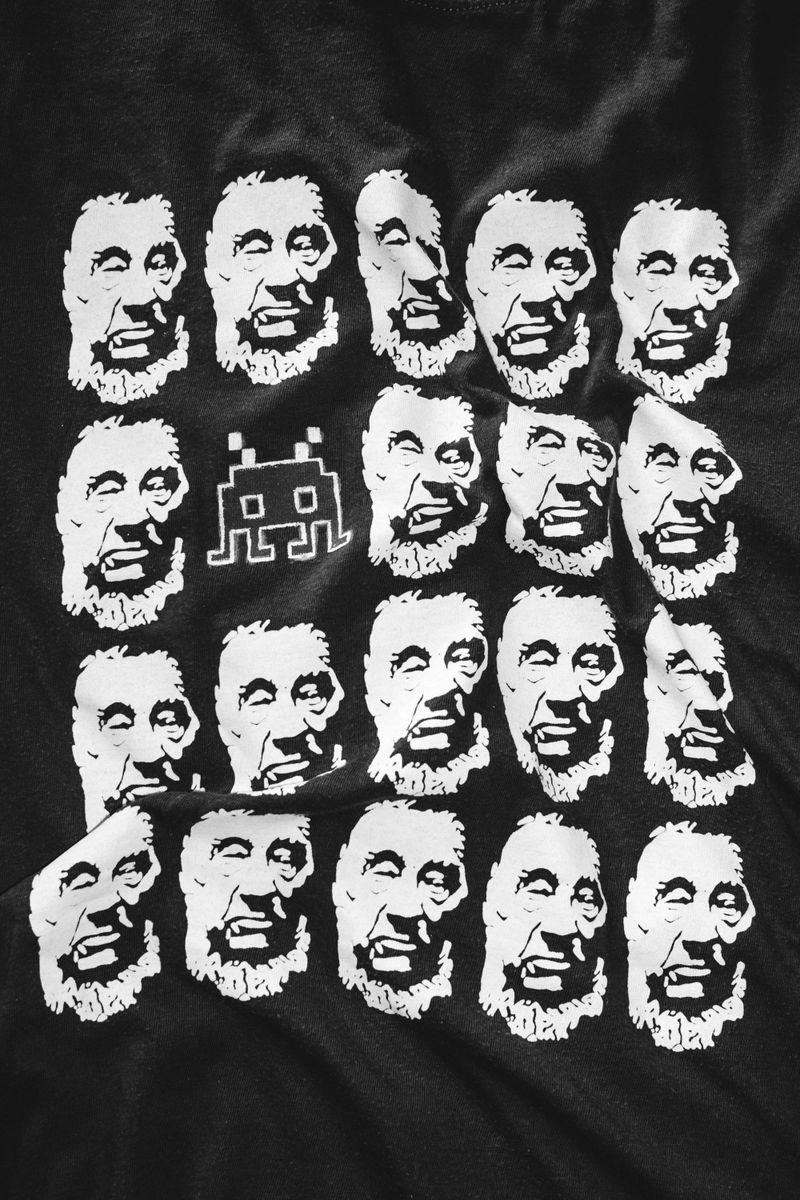

There’s a preacher man that I call dad that lives on the moon.

I hadn’t seen my father in years. His decision to move there had left me angry. Then I got a call - he had a stroke.

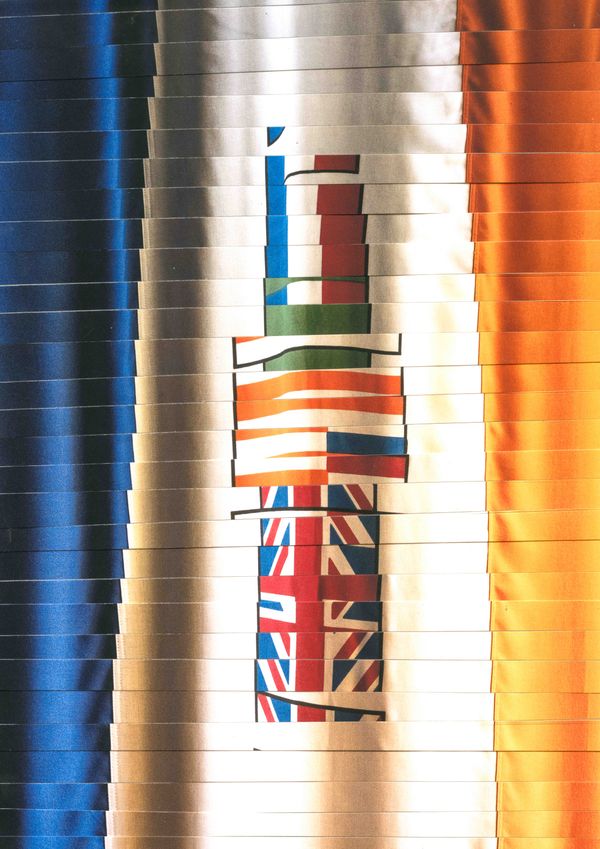

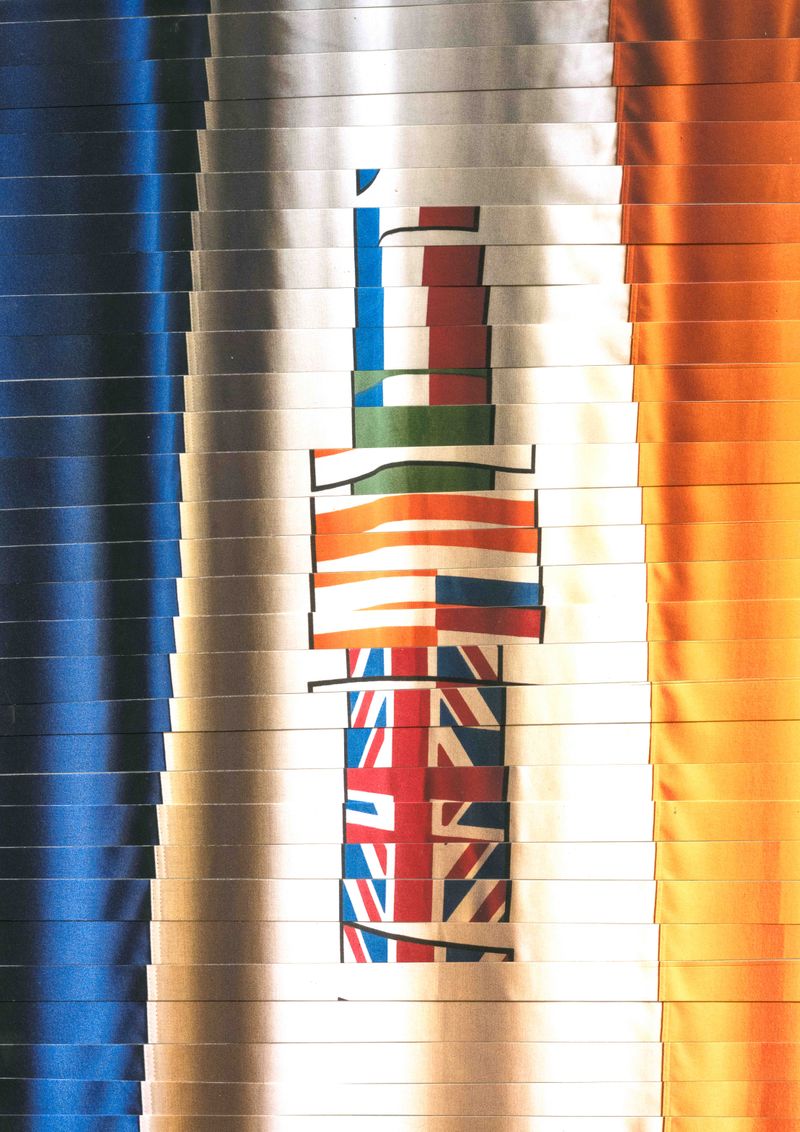

I travelled to this metaphorical moon, a place called Orania in the middle of South Africa, somewhere I’d never been. He had relocated from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal drawn to an Afrikaner dream and fearing for his safety and wellbeing of the country.

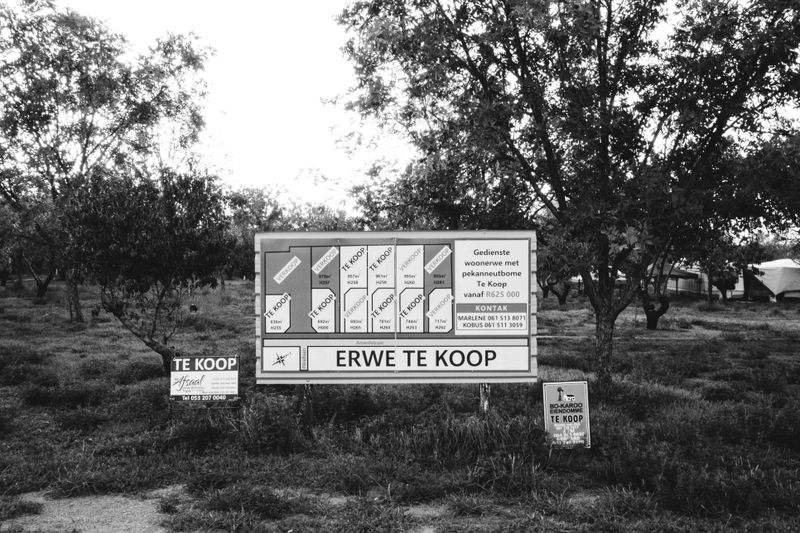

Orania was purchased in 1990 by Professor Carel Boshoff III, son-in-law of Hendrik Verwoerd, the father and architect of Apartheid. It was bought as a cultural homeland for white Afrikaners after apartheid fell.

Before the Afrikaners moved in during 1991, the former coloured inhabitants were forced out in one of the last large-scale forced removals of Apartheid. The town’s vetting process ensures only Afrikaners can live and work there, effectively excluding Black people. Critics call it a separatist enclave. Supporters like my father call it cultural preservation. Its existence and autonomy are protected by Section 235 of the South African Constitution, which allows self-determination of cultural groups.

The moon is a metaphor for Orania, where he lived from 2018 until early 2025. It represents the emotional and ideological remoteness, the surreal state of post-apartheid whiteness - detached and uncertain of its place. Even after he left, the distance persists. I’m an insider because of my father and my culture, but an outsider because I remain uncertain of what it means to be an Afrikaner. My relationship with him exposed me to a version of Afrikaner identity which I reject.

My visits became a mirror for larger questions about belonging, whiteness, and the persistence of segregation - the ways these beliefs continue to reproduce isolation under the guise of preservation.

This work is a personal exploration of the distance between a daughter and her father - emotional, ideological, physical, religious and political. It grew between love and discomfort, between past and present.