If you can read the ocean you will never be lost

-

Dates2014 - Ongoing

-

Author

My ongoing documentary challenges colonial narratives of the last U.S. leprosy settlement on Molokaʻi. It integrates images, sound, and research to document the final years of the last remaining residents and reveal a resilient community's history.

If you can read the ocean you will never be lost, 2014—ongoing

The remote Kalaupapa Peninsula on the Hawaiian island of Molokaʻi is a site of profound contradiction: a place of forced exile that became an unlikely home, and a landscape of historical trauma. This long-term expanded documentary project documents the final years of the last remaining residents at this U.S. leprosy settlement, providing a critical counter-narrative to the authoritarian and colonialist accounts that have long dominated its history. Currently, only six people from the Hansen's disease registry remain in the Hawaiian Islands, with three residing at the Kalaupapa settlement and three at the hospital in Honolulu.

From 1866 to 1969, due to epidemic infection rates, the Hawaiian government enforced a policy of forced exile, transforming Kalaupapa into a century-long prison for individuals diagnosed with Hansen’s disease (known in Hawaiian as Mai Ho'oka'awale, "the separating sickness"). The peninsula's geography, with the Pali (sea cliffs) plunging 2,000 feet into the Pacific and featuring the 26-switchback trail as the only land access, was seen by settlers as a barrier and a tool for isolation and severance. In contrast, for Native Hawaiians, they merely hiked the Pali or sailed the seas for a means of passage. The two distinct, separated portions of the island are known locally as "Topside" (the main portion of the island) and "Backside" (the northern side of the island, where the settlement is located). Today, entry to the settlement is also provided by an airport with one of the shortest landing strips in Hawaiʻi, located right on the northern tip of the peninsula, a ten-minute flight from Topside.

My work contributes to a reconstructed history of Kalaupapa by challenging the colonial narrative of salvation. This narrative, promoted by settlers and the Church, centered on Saint Damien and Saint Marianne Cope, who were both canonized for their dedication and good work at the settlement among the banished. However, this narrative has long obscured the fact that Native Hawaiian residents initially offered care to the first exiled Hawaiians. This earlier care was an act of true ʻohana (family), in which the original inhabitants took in the banished individuals as their own kin, demonstrating a profound act of cultural compassion before the arrival of the settlers. By incorporating newly translated first-hand accounts, chants, and poems from former residents, this project refutes the colonialist claim that foreign intervention was required to save the community. It was the U.S. occupation of Hawaiʻi that solidified Kalaupapa as a prison, forcibly removing original inhabitants and their families to protect the economic interests of American-owned plantations.

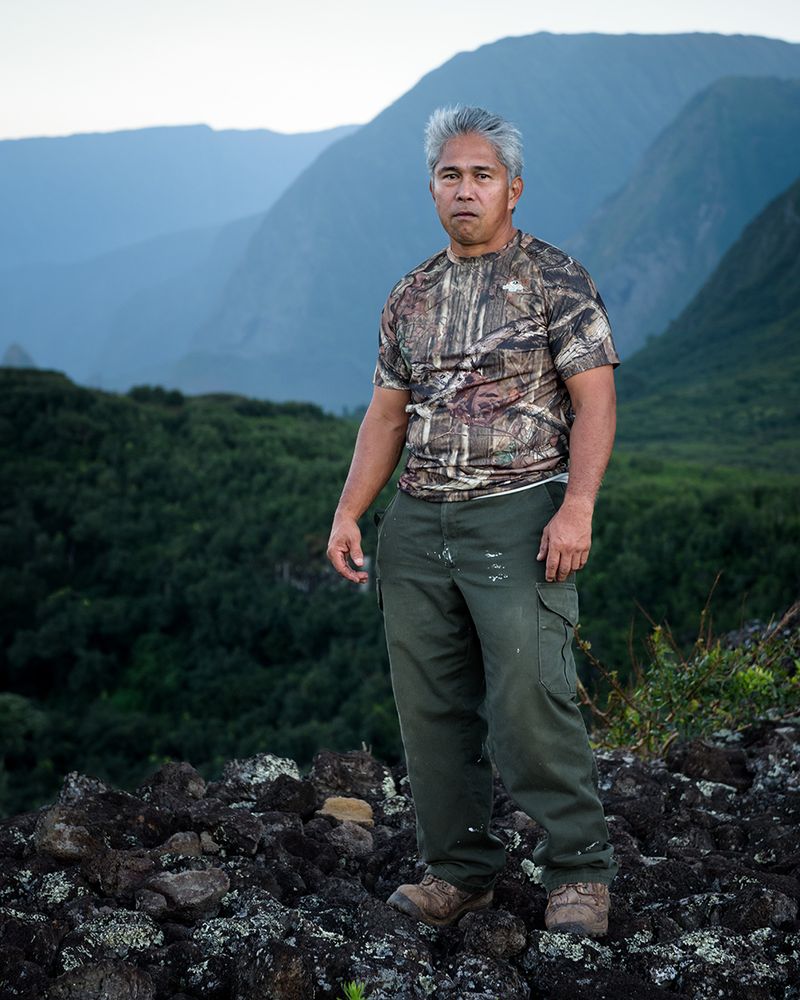

As the granddaughter of white settlers who grew up visiting Molokaʻi but never the settlement, my decade-long commitment to this work provides a unique vantage point on the complex narratives often ignored by the mainland community. My methodological approach uses an expanded documentary practice, combining still color photography, moving images, sound, and archival research. Gaining entry to the settlement is a difficult, multi-leg journey requiring several waivers and an on-site sponsor, allowing me to stay for only six days while bringing all my own supplies. I have successfully navigated this process four times now, demonstrating my commitment to completing this critical documentation.

I plan to return to Kalaupapa to complete sensitive portraits of the last remaining residents and to work with archival materials from the Kalaupapa Museum. This vital collection includes patient-created art, tools they made to adapt their lives, relics from ancient Hawaiians found in the settlement, photographs, and letters. With the settlement recently reopened, I am ready to return and continue this critical work.

Ultimately, this project seeks to honor the resilience and strength of the Kalaupapa community, preserve historical memories, and challenge the prevailing narratives of isolation and despair. The final body of work will investigate the peninsula's transition from an indigenous homeland to a prison, a hospital, and now a National Historic Park. The settlement is currently administered by the Hawaiʻi Department of Health, which runs the hospital, and the National Park Service. The presence of over 8,000 graves throughout the settlement underscores the history of this land as a permanent home for the exiled.

The PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant is vital for fully realizing this critical inquiry, ensuring that a story narrated from a female perspective helps to confront this overlooked part of our national history and address the powerful question of the land’s future. The final phase will be a solo exhibition at the Molokaʻi Public Library (Topside) and the Kalaupapa National Historical Park & Museum (Backside), with panel talks featuring academics and local residents. These talks are crucial for engaging the local community in a process of re-education and communal reflection. With the National Park Service currently renting the land and pushing for a permanent park, while local residents advocate for a return to homestead land, my work becomes a critical effort to document the community's vision for a future where the stories of Kalaupapa are told with the dignity and completeness they deserve.