I Love You Like The Moon

-

Dates2023 - Ongoing

-

Author

A magical-realist portrait of the moon and the femme, blending myth, nature, and the body. Blurring documentary and dream, the work reclaims lunar space as a site of resistance, power, and collective re-enchantment.

Excerpt from text by curator, writer, Sofia Thieu D'Amico:

Drawing Down the Moon

In I Love You Like the Moon, Orejarena constructs a speculative, feminist cosmology in which the moon becomes a site of inhabitation without colonization, a commons beyond terrestrial regimes of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy. Through poetic image pairings, material alterations, and the collapse of photographic realities, Orejarena dissolves binaries of fact and fiction, subject and landscape, human and celestial, positioning femme bodies as integral to an imagined lunar terrain. Drawing from surrealist lineages, queer and feminist theory, and cosmologies historically suppressed under modernity, the project imagines the moon as a space of fugitivity, relationality, and collective world-building. Here, photography functions as an encounter charged with intimacy, memory, and desire. By centering cyclical time, synchronicity, and speculative futures, I Love You Like the Moon offers the moon as both mirror and methodology: a luminous framework for dismantling dominant visual regimes and envisioning emancipatory worlds still to come.

Artist Statement:

I Love You Like the Moon is a magical-realist portrait of the connection between the moon and the femme—expressed through nature, the body, and myth. The project begins in a documentary mode, photographing my friends and myself in the rhythms of everyday life. Gradually, the images transform—employing the language of surrealist solarization to build dusty, luminous, lunar images—until the figures appear to exist on a lunar landscape. This metamorphosis mirrors a passage from the earthly to the cosmic, a search for the people, places, and energies that radiate with femme life.

As the current political climate continues to weigh on femme bodies, I Love You Like the Moon imagines an alternate space of refuge and resistance. Drawing from cross-cultural myths and rituals that have linked the femme to lunar cycles for centuries, the project envisions the moon as both sanctuary and site of power—a place where the femme resists erasure by re-enchanting itself.

Historically, the race to the moon was a masculine project of conquest and control. My work instead subverts that narrative, offering a femme counterpoint a journey inward guided by intuition and transformation. Combining diaristic and collective imagery, I Love You Like the Moon plays with what an archive can be—an ever-shifting constellation of bodies, myths, and memories.

The series employs a range of photographic processes and materials to collapse boundaries between documentary and fiction, past and future, personal and collective. In doing so, it seeks to break from the hyper-masculine visual canon and instead presents as a series of fragmentations—reflecting the way femme experience, mythology, and history have been scattered, erased, and reassembled across time.

Full text by curator, writer, Sofia Thieu D'Amico:

Drawing Down the Moon

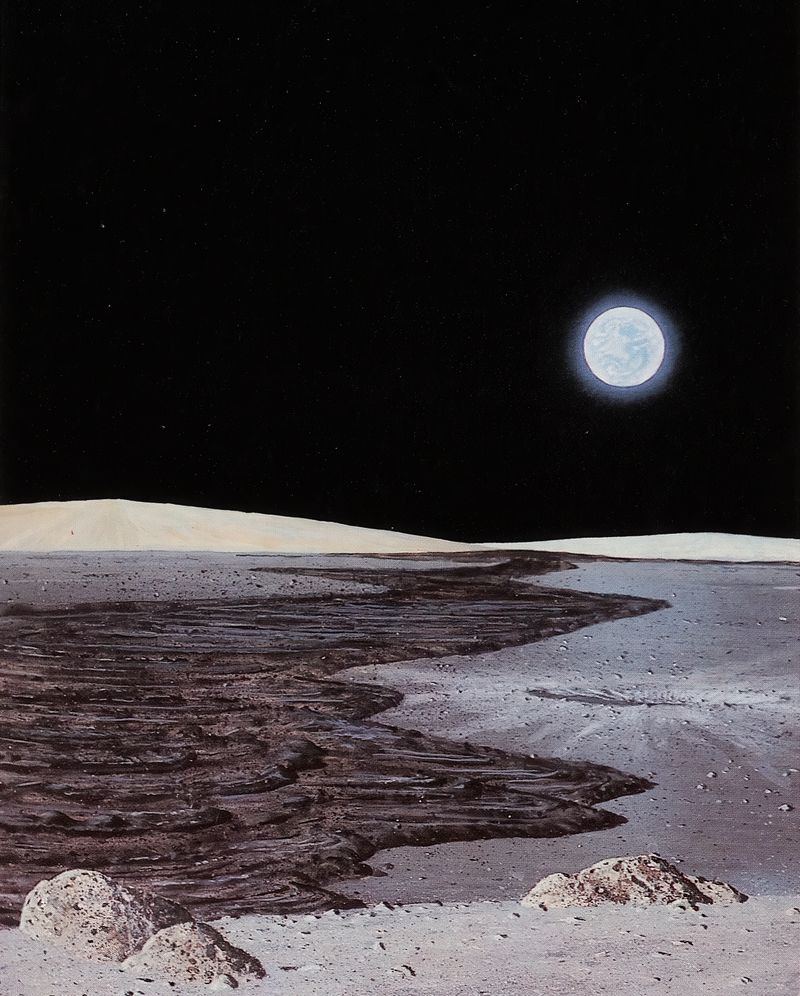

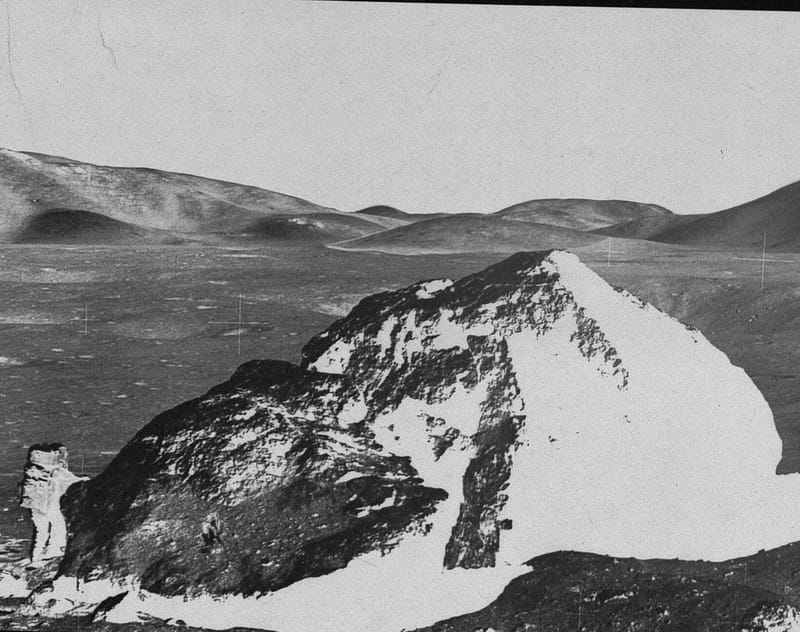

Early astronomers once believed that the surface of the moon held vast oceans. Telescopic images of darkened patches—observable lunar maria—led to the naming of Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) and Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility). We now understand these lunar seas to be impact craters filled with ancient volcanic flows. Yet in Andrea Orejarena’s latest photographic series, I Love You Like the Moon, we encounter a lunar landscape reimagined in which women stand on the rocky shores of cosmic seas and bathe freely in their lucent waters.

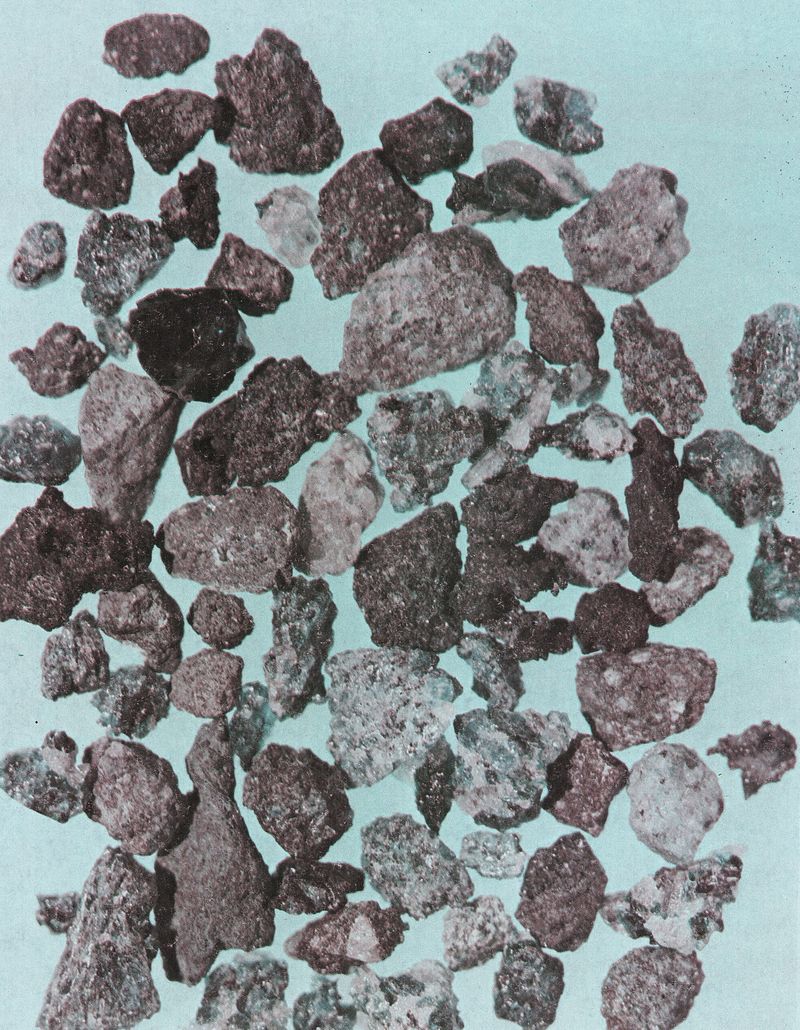

Using a range of photographic techniques and imaging methods—archival, found, and altered images of the moon paired with personal photography—Orejarena constructs an alternate reality with a magical-realist inflection, one that feels at once mysterious and complete.

In the opening images, two horizons interlock seamlessly across facing pages, as if they were one. The first appears decidedly lunar, and so, too, does the second. But is that also the moon hanging in the right corner? Though unified, there is a slippage of reality between the images. I find myself asking: Is this really the moon? Or is it not? I try to separate fact from fiction, only to realize I am missing the point entirely—between these two covers, it is all lunar.

From these photographs I can feel an astral silence, deep and distinguished, so complete it seems I might hear my own blood moving through my veins. On the following pages, a figure swims through greyscale currents beneath a black sky. Next comes a painterly, uncanny landscape: a dark, molten river zigzags through it, as if flowing directly from the previous pages. The river meets a gray—almost lavender—ground, a crater, with stark white hilltops rising in the distance. An obsidian sky hangs overhead, speckled with stars like archival dust mites. To the right, the eye is carried down that starry sky to waves breaking on a white shore, marked by scattered human footprints. An impossibly elongated silhouette stretches across the lunar beach—surely an alien woman. We have touched down on the moon at last, and the universe looks on expectantly. As if one could sigh with relief on the shore, and an old, heavy sound from space might answer back.

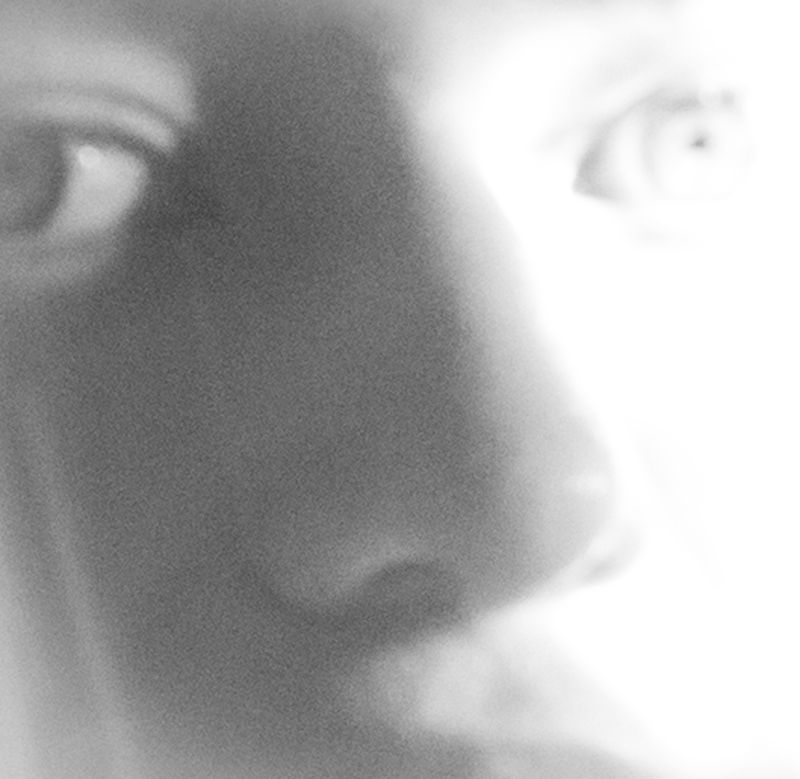

Throughout I Love You Like the Moon, poetic pairings collapse photographic realities, dancing the line between perceivable truth and fantasy. Light bleeds, motion blurs, image grains, and other subtle distortions push these photographs deeper into a surreal register. At the same time, the edges, speckles, and folds of Orejarena’s human subjects echo the hilly astral dunes and coarse lunar rock that surround them. Diaristic portraits of femme figures and close-ups of bare skin feel simultaneously intimate and otherworldly. Their postures communicate an embodied power born of complete, candid ease: a dozen alien Venuses on the half-shell. Indirect or oblique views partially obscure the subject in a reciprocal, equalizing mode. Burnishing brightly like the halo of an eclipse, Orejarena’s figures pick extraterrestrial flowers, recline on lunar sands, or lie cloaked in the dark velvet of deep space.

What brought them to the moon? Why are they there? I asked Orejarena.

Why not? Why wouldn’t they be there? They’re just there, she replied.

We both smiled, nodded in alignment, and passed understanding silently between us.

Of course, we’re on the moon, I think. It is only the most natural place for us to go. This is especially true, perhaps, in a turn towards speculative fiction as a political tool in an increasingly fraught world. In her critical text When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics, postcolonial theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha cites a popular Chinese proverb: “The same moon that rises over the ocean lands in the tea water. The wind that cools the waters scatters the moons like rabbits on a meadow.” Minh-ha elaborates: “The one moon is seen in all waters; and the many-one moon is enjoyed or bawled at on a quiet night by people everywhere—possessors and dispossessed.” Moonbeams cast upon the earth in the interiority of night suggest the bridging of shared, disparate worlds, a site of transformation, or what Minh-ha calls “the site of possibility for diversely repressed realities.”

If we are to engage in a planetary mode of thinking, the moon offers multifarious readings. Though humans have reached its surface through the projects of the Space Race, it remains largely inhospitable. International space law—the 1967 Outer Space Treaty—prohibits any singular national ownership of celestial bodies. Operating outside terrestrial regimes of territory, borders, and property, the moon—our closest planetary neighbor—emerges as a speculative site for negotiating new ontologies and world systems.

When I first encountered I Love You Like the Moon, I immediately thought of Surrealist painter Remedios Varo’s Papilla Estelar (Star Maker), which depicts a woman in a tower grinding stardust into a stellar porridge to feed a caged crescent moon. In both works, narrative backstory recedes in favor of the primacy of image and poetic association. Orejarena’s photographs resonate with Papilla Estelar’s symbolism: an intimate relationship with the cosmological and the radical creative potential of tender, potent feminisms. As a world-building exercise and a form of civic imagination, I Love You Like the Moon casts off terrestrial social orders—namely the interlocking triad of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy—particularly in service of femme-identifying and subaltern liberation.

This impulse aligns Orejarena with Surrealist figures such as Varo and Leonora Carrington, women who turned to mysticism, magical imagery, and occult practices to transcend masculine art-world spheres. Art historian Susan Aberth writes that, “In a proto-feminist spirit, they used the language of occultism—with its aura of danger and rebellion—to set themselves apart from the mainstream art world… It was the rebellious nature of Surrealism itself, and the fact that it embraced women artists to a greater degree than other art movements before it, that encouraged them to embark on this journey.” Varo and Carrington often depicted androgynous and non-gendered beings as self-portraits, mystical figures, or hybrid creatures. Orejarena’s practice similarly channels lineages of sapphic queer theory and activism, with I Love You Like the Moon embracing an expansive spectrum of gender identity. By turning toward speculative futures, we may begin to displace the limited, dualistic thinking that structures our present moment.

This entanglement also rests on historical precedent. In Caliban and the Witch, Marxist feminist theorist Silvia Federici argues that the suppression of magic, folk practices, and communal knowledge—particularly that held by women—was a crucial political strategy in the emergence of capitalism. As Federici writes, “Equally incompatible with the capitalist work-discipline was a conception of the cosmos that attributed special powers to the individual.” Fantastical thinking, divination, or the fulfillment of desire without labor ran counter to the production of a controlled workforce. Relational, animistic cosmologies were replaced by secular, mechanistic worldviews that enabled the enclosure of the commons, reinforced patriarchal family structures, and subordinated women’s bodies as regulated means of production. The Surrealist legacy of women artists like Varo and Carrington stood in opposition to these forces; their entire artistic ethos was to dismantle them.

Orejarena’s work takes up this same mantle, while also gesturing towards the persistent oversaturation of masculinity specifically within the field of photography—from its recorded inventors to its institutional frameworks. And yet, the first photography book is widely attributed to botanist Anna Atkins, whose 1843 volume Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions predates the canon. Within photography itself, Orejarena continues a legacy of women’s photography books, and an ontological decentering is enacted. In I Love You Like the Moon, the traditional viewfinding cross is duplicated and dispersed across images, signaling multiple focal points and perspectives. What was once a singular target becomes a constellation of near-sacred icons: a shift from the singular toward the collective. Inversions of positive and negative further destabilize binary thinking—of light, of gender, of perception. These images emerge from an intimate, affective, relational encounter between photographer and subject, one that resists documentary extraction. As Ariella Aïsha Azoulay writes, a photograph “does not possess a single sovereign, stable point of view,” but is instead “the product of an encounter of several protagonists.” For Orejarena, photography becomes an unfolding process, suffused with life and memory—here, memories not yet lived, but dreamed.

Another allegorical facet of I Love You Like the Moon is its vision of inhabitation without colonization. In a departure from dominant science-fiction tropes, there are no spacecrafts, visible architectures, military bases, or futurist settlements. Instead, Orejarena turns toward the minutiae of the landscape: mineral veins, undulating craters, shifting sands. Like lunar nymphs, her subjects exist within an astral wilderness, perhaps having discovered a new commons. The moon becomes a blank slate for reimagined world orders and utopian politics.

Theorist Yuk Hui, in Cosmotechnics as Cosmopolitics, calls for a planetary mode of thinking that moves beyond Western, territory-based ontologies to address ecological crisis. “The loss of the cosmos,” Hui writes, “is the end of metaphysics.” He argues for a new cosmopolitics—a politics of the cosmos—that exceeds hegemonic frameworks. We might see a permutation of this argument in contemporary feminist and queer science fiction, such as Octavia Butler’s Earthseed series, which looks to the stars for human survival. In an increasingly conservative political climate that threatens the autonomy of women, transgender, and nonbinary communities, the moon may yet be drawn down as a site of resistance. There has to be a cosmic alternative.

The queer Chicana poet and theorist Gloria Anzaldúa offered the Aztec moon goddess Coyolxauhqui as a framework for feminine world-building and psychic reconstruction. As depicted by the Coyolxuahqui monolith found at the Templo Mayor, in Tenochtitlan, Mexico, dismembered and cast down by her brother, Coyolxauhqui’s fractured body becomes, for Anzaldúa, a model of reassembly.“The Coyolxauhqui imperative is an ongoing process of making and unmaking,” she writes. We must destroy or escape one world in order to create another. This epistemology requires coming undone: a fragmentation of identities, signifiers, and systems fueled by shifting phases of the ever-changing moon. Similarly, I Love You Like the Moon channels an alchemical process of reconstitution, by collaging source material—the creation of novel images—to dream a new reality into being: one rooted in fugitivity, community-building, and emancipatory projects.

It is both elementary and endlessly fascinating that women’s bodies visibly mark cycles, in ways men’s bodies do not, aligning with the moon’s waxing and waning. These lunar shifts are echoed again in menstruation, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause. In ancient Greek regions, women gathered during the full moon to honor the moon deity Artemis, who presided over childbirth and these female life transitions. The full moon served as both symbolic witness and source of power for their ceremonies. It also offered practical gifts: natural illumination, safer night travel, and the possibility of outdoor rituals without torches. Women could gather beneath the moon after the day’s labor had ended, when domestic responsibilities were complete.

Across Roman, medieval, and early modern Europe, women were also advised to cure and dry foods during the waning moon and to avoid beginning preservation near the full moon, believing that food cured during the waning phase would keep longer. Though often linked to superstition, this practice carried scientific sense: waning-moon nights were darker, reducing insect activity around exposed food, as well as human activity and opportunities for contamination. While the mystical explanations are many, the practical benefits of aligning one’s activities with the moon should not be overlooked.

I find great comfort in these twin qualities: a nuanced cosmology that looks skyward for information, and the quiet assurance that the answers can indeed be there. Like many, I am still learning how to tune out the internalized misogyny that insists I distrust my own knowledge. From a contemporary standpoint, much work remains—destigmatizing menstruation, unlearning the male gaze and compulsory heterosexuality, and creating the conditions to explore gender identity with full freedom and subjectivity. I see I Love You Like the Moon as an invitation to recommit myself to these responsibilities, and in doing so, to locate myself within a long lineage of shared, radical thought. Just the same as when I see the moon hanging heavy and warm in Earth’s atmosphere, it offers the chance to build a deeper intimacy with my surroundings—to be reenchanted, and to fall in love with the world again, despite its limitations. Through her images, Orejarena returns this reality to us: one in which the work has already been done. Perhaps we have been performing rituals all along.

In I Love You Like the Moon, Orejarena constructs a speculative, feminist cosmology in which the moon becomes a site of inhabitation without colonization, a commons beyond terrestrial regimes of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy. Through poetic image pairings, material alterations, and the collapse of photographic realities, Orejarena dissolves binaries of fact and fiction, subject and landscape, human and celestial, positioning femme bodies as integral to an imagined lunar terrain. Drawing from surrealist lineages, queer and feminist theory, and cosmologies historically suppressed under modernity, the project imagines the moon as a space of fugitivity, relationality, and collective world-building. Here, photography functions as an encounter charged with intimacy, memory, and desire. By centering cyclical time, synchronicity, and speculative futures, I Love You Like the Moon offers the moon as both mirror and methodology: a luminous framework for dismantling dominant visual regimes and envisioning emancipatory worlds still to come.

Orejarena cites her personal relationship with the moon as a major driver of the project. But perhaps even more central are what she describes as “lunar occurrences,” a term the artist coined to name particularly powerful and meaningful coincidences between people who are emotionally linked—moments in which shared experience becomes strangely permeable. One might imagine these occurrences as a kind of planetary alignment of consciousnesses: as if the shared gravitational orbit between two people pulls their outer realities closer together. This can be felt, for instance, in a parent’s intuition toward their child: often there is a sudden “knowing” when they are apart and something is not quite right. Yet the most potent lunar occurrences also arise in the lighthearted randomness of everyday life—in synchronic alignments such as dreaming of someone you haven’t spoken to in years, only to wake and find they have reached out, or when two people say the same thing at the same time and the radio echoes it back moments later. “That’s so lunar,” Orejarena might say.

An experience might be paradoxically “lunar” while remaining deeply embodied. Many such moments were shared among the very subjects depicted in I Love You Like the Moon. The psychoanalyst Carl Jung writes in Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle that the “mutual attraction of related objects,” in what he terms “elective affinity,” gestures toward “...the dream of a greater and more comprehensive consciousness, which is unknowable.” What we do know, at least, is that these lunar occurrences draw us into imaginative modes of thinking while generating a felt intimacy and connection among those who share them. When witnessed, they can only delight the observer. I cannot imagine why we would deny ourselves the pleasure.

In the absence of oceans, lunar maria, the moon instead churns our earthly waters, pulling the tides and our aqueous bodies alike. As a result, many note meaningful and serendipitous coincidences in which the lunar phases align with personal experiences, whether the menstrual cycle’s alignment with the lunar month, emotional intensities on the full moon, or major transitions with the new moon. Through various cycles, tides, and tendencies, our intimate relationship with this distant, glowing body is at once improbable, and at the same time, dazzlingly evident.

Of course, we live on the moon.

How natural. How obvious.

How loving. How lunar.