Dust

-

Dates2017 - 2017

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues

- Location Russia, Russia

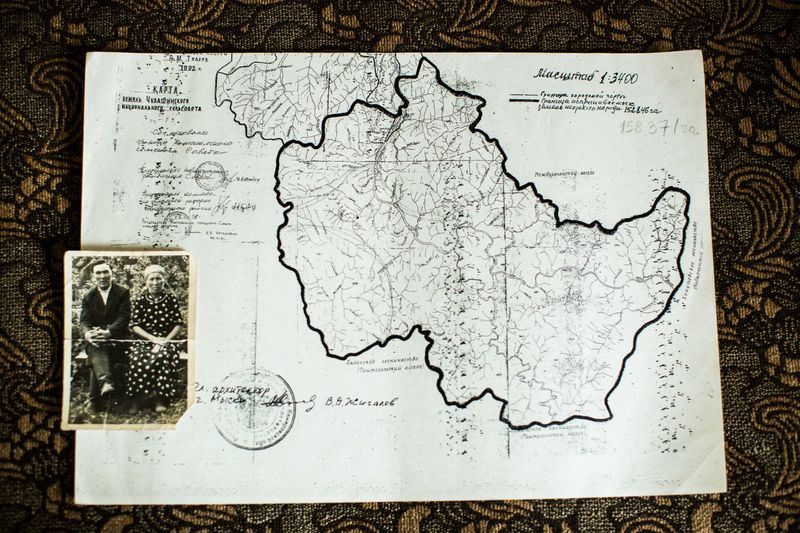

The indigenous Shors, a Turkic people whose survival and beliefs are intimately tied to the nature around them, and have had their ancestral lands and villages ravaged by mining, leading, many say, to the slow death of their culture and way of life.

Coal is the single biggest contributor to man-made climate change and deforestation accounts for up to a tenth of current carbon dioxide emissions.

Russia is the world’s sixth-biggest coal producer and has the largest area of tree cover in the world, with 882 million hectares of forest (2017). Between 2001 and 2016 Russia lost more forest than any other country in the world.

According to the Siberian Customs Administration, more than half of all the coal exported from Kuzbass ends up in the EU, with the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Germany among the prime markets. 70 - 80 per cent of mining in Kuzbass is opencast and the methods bring their own dangers: threatening the health of those who live nearby, as well as the surrounding environment, with air, water, soil and noise pollution. It has razed forests, blackened rivers, contaminated the air with dust, and created waste mounds.

Russian mining companies intentionally mine close to existing population centres, rather than in less populated areas. This cuts infrastructure costs – including roads, railways, electricity grid and water mains, as well as providing readily available labour.

All who live in the vicinity of the mines are prey to their impact. Official statistics reveal increases in tuberculosis, cardiovascular diseases, maternal and child illnesses and a shortened life expectancy. The paradox, though, is that many locals’ livelihoods are dependent on the mines that are causing them such harm.

The indigenous Shors, a Turkic people whose survival and beliefs are intimately tied to the nature around them, and have had their ancestral lands and villages ravaged by mining, leading, many say, to the slow death of their culture and way of life. It’s estimated that in the past seven years, the Shor population of the region has declined by almost 50 per cent.

Those who live there say the region has become a moonscape from which many are desperate to escape.

Words: Anne Harris

Photo: Sally Low