Zed Nelson On His Exhibition The Anthropocene Illusion at PhEST

-

Published19 Feb 2026

-

Author

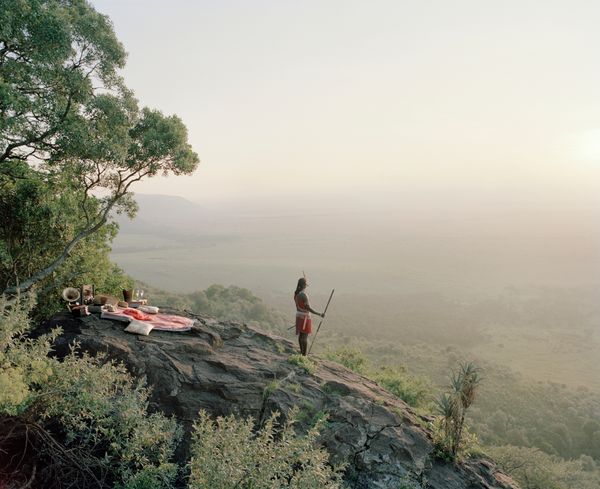

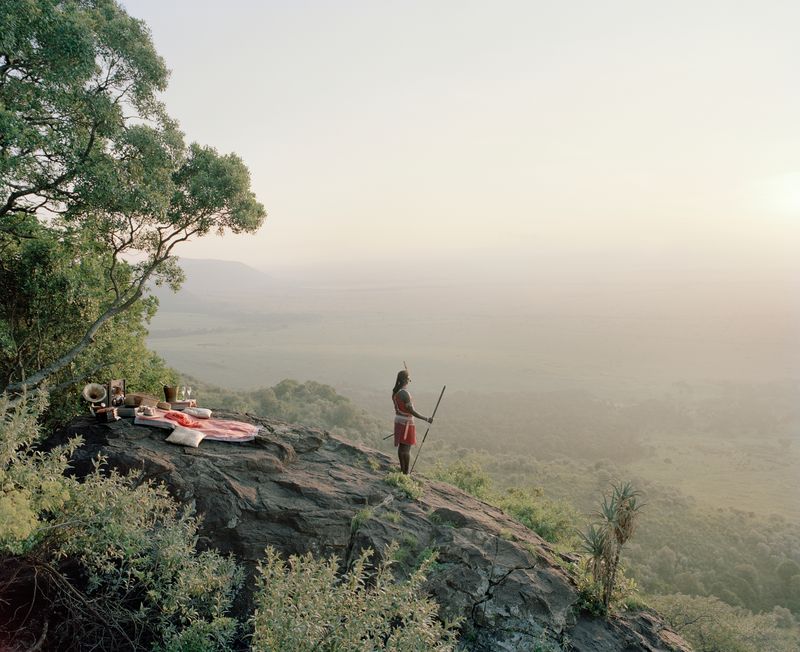

Why do we retreat into artificial experiences of nature, and what contradictions do these imply? Displayed in the Italian festival through the PhMuseum 2025 Photography Grant, The Anthropocene Illusion reflects and draws on the simulacra we create.

During the 10th edition of PhEST, the Monastero di San Leonardo and its courtyard in Monopoli hosted Zed Nelson's tableaux of staged, choreographed nature. Real plants merged with the surface of his prints, intervening along the blurred boundaries which the photographer has been inquiring for now over six years – reality and representation, truth and illusion, authenticity and simulation.

Selected through the PhMuseum 2025 Photography Grant by Giovanni Troilo and Arianna Rinaldo, the exhibition of The Anthropocene Illusion brought this long-term project to inhabit a new context, reaching to a new public. As a new artist will soon be granted with the same opportunity through the Grant's current edition, which accepts applications until February 19, we spoke with Zed Nelson to deepen into his practice, impressions of the festival, and thoughts on photography's political role.

Hi Zed, The Anthropocene Illusion addresses the issue of a natural environment that is increasingly mediated, constructed, and staged. When did you first realise that our relationship with nature was becoming more of a representation than a direct experience? What motivated you in starting the project?

Ten years ago, I visited an Arctic Experience museum and aquarium called Polaria, located in the far north of Norway. There I found a bearded seal lying on fiberglass rocks decorated with fake ice, illuminated by artificial light. I wondered why we would come to observe a living seal in these conditions – a crude, artificial simulation of nature - when we were only a few meters from its natural habitat. This scene haunted me.

After this I began to see this artificial representation of nature everywhere. Singapore is a striking example. It’s known as the Garden City, full of foliage and hanging, rooftop gardens. On the surface, it’s a triumph of green design—but city laws demand regular pesticide spraying to destroy insects. So it looks like a beautiful green environment, but without an ecosystem. In national parks like Yosemite Park in the United States, visitors experience 'wild' nature in a reassuring, curated environment. In South Africa, tourists pay to pet and feed farmed lion cubs. Once fully grown these animals end up being killed by Western trophy hunters who pay to hunt these semi-tame lions in a fenced area from which they cannot escape. You can go to Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida—a simulated version of Africa, complete with mountains, restaurants, and live ‘wild’ animals like hippos and rhinos. It is a sanitized, commodified version of Africa—an Africa you can visit safely, with snacks and smooth concrete walkways, designed entirely for human enjoyment.

My project examines these blurred boundaries between illusion and reality. We are living in a collective self-delusion. We have separated ourselves from the land we once roamed and from other animals. But somewhere deep within us the desire for contact with nature remains. So, while we destroy the natural world around us, we have become masters of a stage-managed, artificial experience of nature, a reassuring spectacle, an illusion.

What do zoos, theme parks, and safaris reveal about our desire for connection and, at the same time, about our inability to fully confront the environmental crisis?

We build artificial, choreographed versions of nature—simulations that offer reassurance, concealing what we’re actually doing to the planet. It is a comforting alternative reality that masks our devastating impact on the natural world, even from ourselves. We are engaged in a project of grand self-delusion.

From breakfast with living penguins at a hotel in China, to vacations in Europe's largest indoor rainforest in Germany, to artificial ski slopes in Dubai, the project aims to question our increasingly fractured relationship to nature. On the one hand, we devastate the natural world, and on the other, we crave a connection to it, building a stage managed, artificial version of it. There's something contradictory in what we do, a psychological disconnect that can be described as cognitive dissonance.

We are living through an era of denial. Climate change, habitat loss, pollution—these are existential threats. Yet political responses remain slow or symbolic, and the recent election of leaders who reverse environmental progress reflects this psychological denial.

Your work was selected by PhEST Artistic Director Giovanni Troilo and Photography Curator Arianna Rinaldo for the 10th edition of the festival in Monopoli with a dedicated layout in the Monastero di San Leonardo and its courtyard, surrounded by real plants. How was your experience working with them, and what was the process leading to sharing your work in this environment?

At first I proposed a more traditional presentation, but Giovanni and Arianna came back with a more interesting exhibition design – indoor images hung in the arches of a monastery, and outdoors in a courtyard surrounded by plants. It was very effective.

Why did you choose to apply for the PhMuseum Grant, and would you recommend applying based on your experience?

It is hard to find funding for a long-term project. For me this means seeking grants, while also working to earn money to support the project. It takes time to produce good, interesting work, and working on a project over time allows for deeper thought and engagement with complex issues. The PhMuseum Grant offers a modest but useful financial prize, but also interesting collaborations and opportunities to exhibit work at several festivals. Winning a prize or having an exhibition helps shepherd a project into the world, in ways that I find hard to quantify or measure. But exposing the work is part of a vital process.

During the closing weekend, you led a guided tour of the festival. What was it like to see The Anthropocene Illusion displayed in such a specific way – requiring visitors to transition from the outdoor greenery, through a doorway, and into a controlled indoor environment? How central is this idea of the boundary between lived and constructed nature within your work?

I really enjoyed leading a guided tour of the exhibition. It drew a large crowd, even though it was the end of the visiting season. The visitors were engaged and full of questions, and it was a really great environment for the exhibition – echoing the themes and contradictions in the work.

Why do in-person exhibitions matter to an artist's career these days? Did your collaboration with PhEST offer any new perspectives on your work?

Exhibiting brings a project into the world, finds an audience, gains press coverage, and builds momentum for the project. People now spend so much time online, that being in a real space, engaging with work directly without distraction, is powerful. For a photographer, presenting their work curatorially and explaining it verbally is an important process. It’s also really nice to be part of a festival with other great shows on at the same time, it becomes a shared experience.

You worked on this project for six years, across four different continents. During this long time, the climate crisis became increasingly visible in public discourse. Did this intensify your sense of urgency or change the tone of the work? Do you believe a project like The Anthropocene Illusion can contribute to a real change, or is its role mainly to raise awareness and ask questions?

That’s a difficult but vital question. When I started as a young photographer, I believed images could change the world. Over time, I became more skeptical. But I’ve come to realise that art’s power lies in storytelling, in education, and in dialogue. Social change begins with communication, with ideas shared and discussed.

Judeo-Christian society introduced a worldview that made people less likely to care about the environment because it promoted humans as superior to, and separate from, nature. With the result that we humans became the primary cause of ecological devastation, and the most destructive creatures on earth.

We need to tell ourselves a new story. Photography can inspire awareness, empathy, and reflection. These are prerequisites for action. Art may not change policy overnight, but it shapes the cultural and emotional context in which decisions are made. Every choice—personal or political—is influenced by what we see, feel, and believe. Art contributes to that shared understanding. It can inspire empathy, and provoke action. In that sense, it’s an essential part of social transformation.

Our future as a species depends on urgent new evaluations of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. It will take a paradigm shift in our priorities and empathies to change. It’s no use just feeling guilty and recycling our milk cartons - it’s on an industrial and political level that change needs to happen. We already have a list of useful ideas: protected natural habitats, ethical treatment of animals, sustainable agricultural practices, rewilding, renewable energy, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and plastic pollution. We know what can be done. We just need to find political leaders and captains of industry who want to do it.

------

PhEST is a festival founded in Monopoli, Italy, dedicated to photography, cinema, music, art and interdisciplinary experimentation. PhEST has entrusted artistic direction to Giovanni Troilo and the photography curatorship to Arianna Rinaldo.

The PhMuseum Photography Grant has established itself as a leading prize in the industry over the past fifteen years, recognized for celebrating contemporary photography and supporting the careers of emerging artists through monetary awards and opportunities across international festivals and online media. Applicants for the 2026 edition are now open, learn more and apply at phmuseum.com/g26.