Photobook Review: The Last Safe Abortion by Carmen Winant

-

Published30 May 2024

-

Author

An account of abortion care labor’s visual culture, Carmen Winant’s latest book is an un-photographic, simultaneous archive living in the present tense.

We enter the basement of an abortion clinic. Dozens of boxes lay on the ground, long unopened. Inside, stacks of pictures record the visual history of abortion being safe and legal in the US. Women speak on the phone, clocks mark the passing of time, hands perform gestures that are meant to be repeated and passed on. Ordinary, instructional, and procedural images of everyday labor speak of a practice now made increasingly unavailable, as the Supreme Court overturned Roe w. Wade in 2022, no longer protecting the right to have an abortion across the country.

“For decades, we’ve had an assault on abortion access and rights in the US. For me, this is about reproductive justice, bodily autonomy, and the right to self-determination”, says Winant. “I’ve always been politically involved, but I've never quite known how to transmute this experience into art. I think I've been a little bit afraid of flattening it out into a subject. But as things felt increasingly more urgent and dire in this country, I knew there was no choice but to do it. Clinics that I would be in conversation with, all of a sudden would close. From one email to the next, a law would come down, and abortion was no longer legal in their State”.

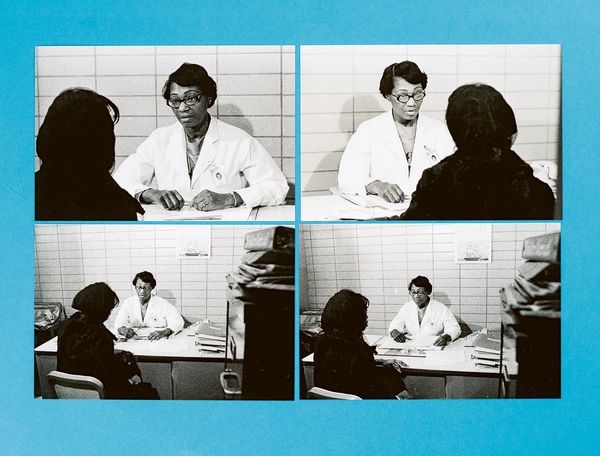

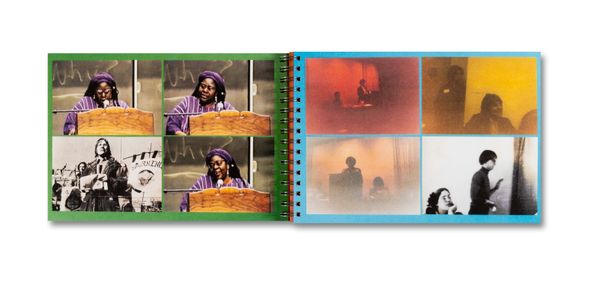

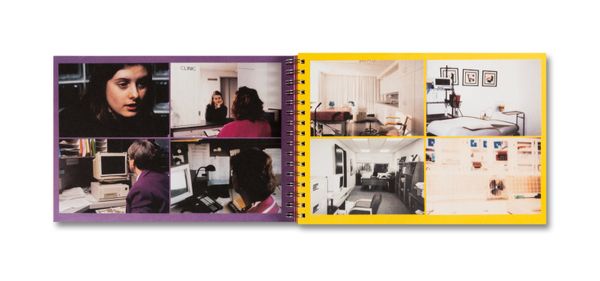

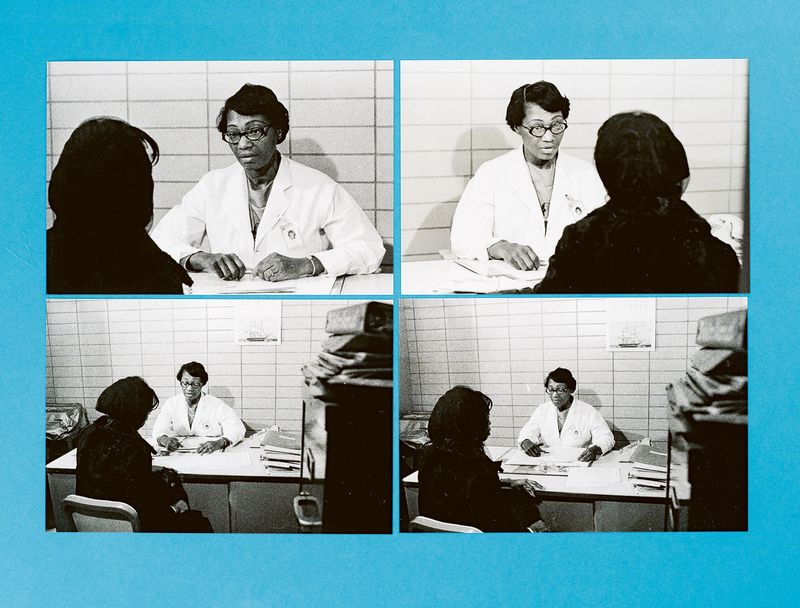

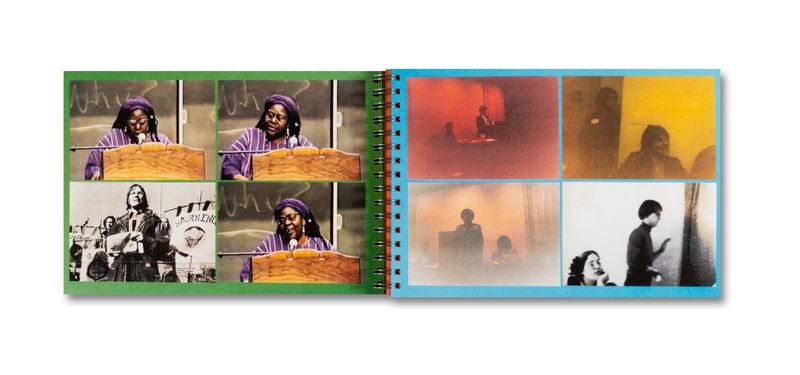

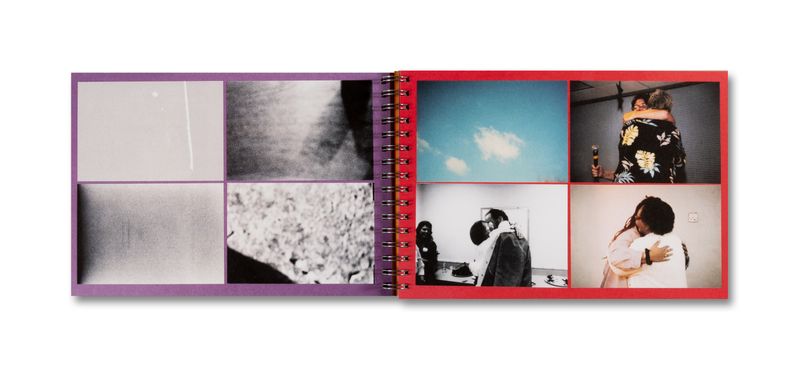

In The Last Safe Abortion, published by SPBH Editions, the boxes in the basement are opened up, and their content is re-arranged and mixed. The scattered images are laid out in grids of four and placed over brightly colored, spiral-bound sheets of paper, reminiscent of the way the same material would be housed in library systems. “When asked to reproduce images, institutional archives scan, or re-photograph them against this type of paper, so that you can easily distinguish the foreground from the background”, says Winant. “For instance, if a photograph had a white border, they wouldn't want to put that against a white sheet. It looks like kind of children's play material, but it's very practical at the same time.”

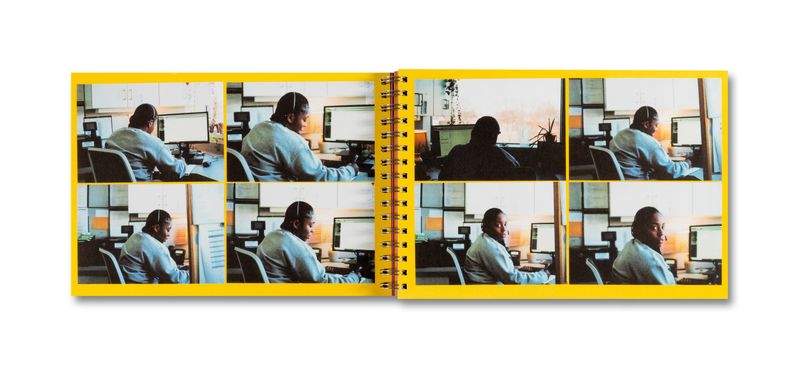

Practicality and systematization are preserved, yet turned in their purpose – the grid is a classifying tool, but it also allows for simultaneity and contamination. There is not one photograph alone, ever – new, ambiguous images are born as we navigate the 8-picture tableaux, now crossing and overlaying in our minds. “Books are so obviously, relentlessly sequential. I’m always fighting that structure a little bit”, explains Winant, “I'm interested in exploding and undoing the way we read photographs. In these groupings, images don’t follow any particular order – they all exist in the same moment. And there is something un-photographic about this. I was trained to shoot rolls, make contact prints, then choose a singular picture. But I always wanted to see it all, simultaneously”.

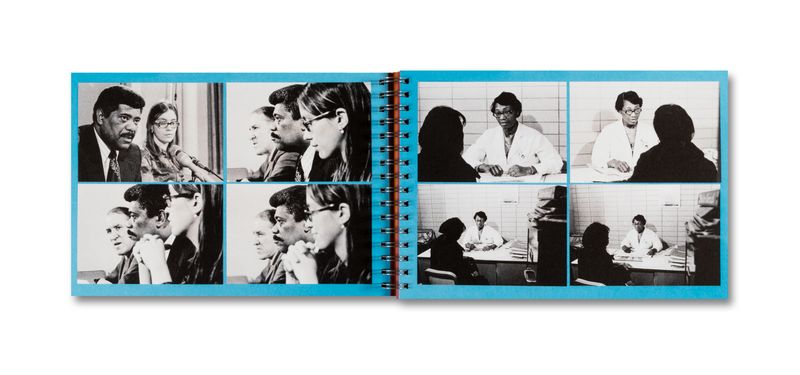

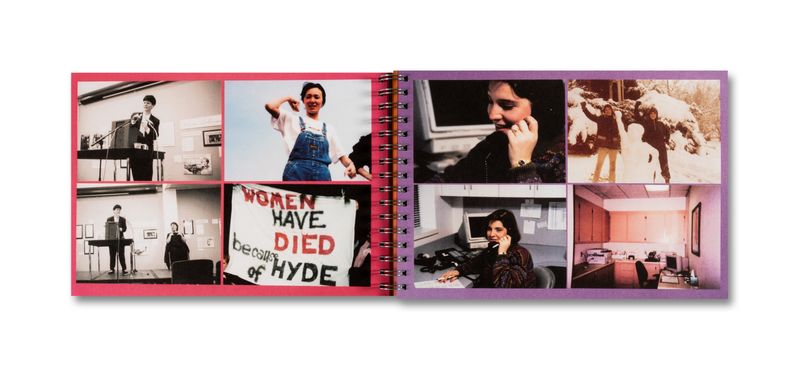

Somewhere in between a movie and an unedited film roll, the images in the grid are repetitive. We see multiple fragments, or points of view of the same split second. It is maybe through repetition that we can enter the clinic smoothly. We circle a table, we hang in the emptiness of a waiting room for longer than we’d want. We cross eyes, and learn to know faces by looking at them from different angles. At times, we are walked out of the building to look up at the sky – and there, as the classifying power of the grid seems to crack, we realise how this story is breathing and alive as long as it merges timelines, biographies and geographies. As long as it is rooted in collectiveness. “So much of the book is about labor”, Winant adds, “and the way the book is structured is a way for me to also reference that. Multiple images of picking up and answering the phone and putting it down, is a way to show time passing across the day”.

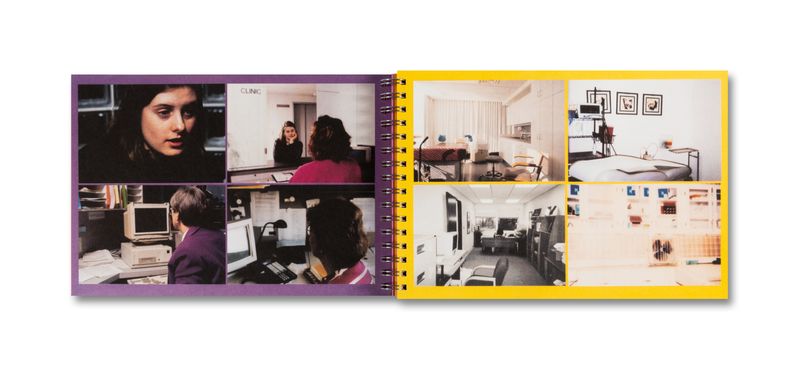

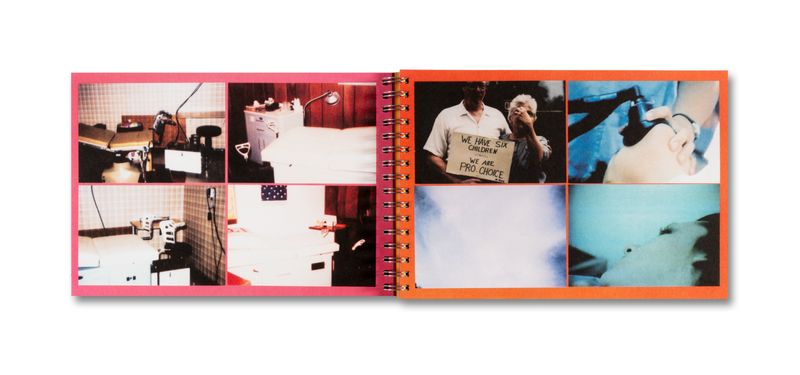

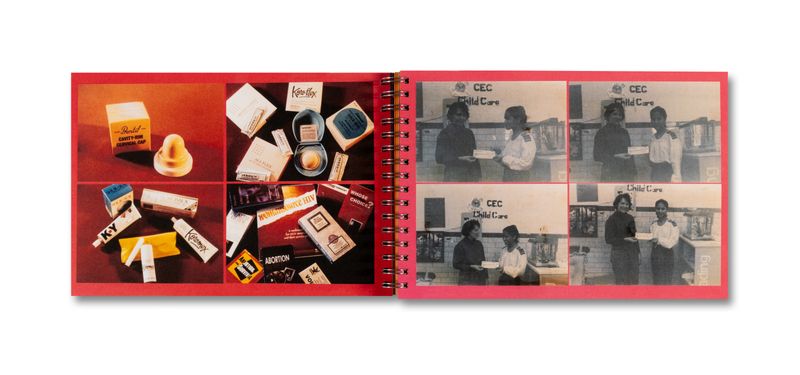

What does the visual culture of abortion care work look like? We move from details of the clinic and staffers, to photographs taken from within the crowd of a pro-choice protest, to instructional sequences showing medical procedure. Overall, the thousands of pictures found in the archives manifest photography at its most practical. “One series of images shows a staffer, Allison, posing as a patient going through the process of getting an abortion”, Winant recalls. “Every step is a photo – she picks up the phone, walks to the clinic, rings the doorbell… These pictures were a tool to teach and instruct. There is a consciousness in why they were made”.

How can this purpose-oriented, almost clinical imagery merge seamlessly with the more casual snapshots – showing life at the clinic and, at times, life outside of it? There is an energy that binds all the photographs together. A net of care and mutual support traverses them all. “There are so many conversations, meetings, and correspondence in the process”, Winant says. “I no longer think of making art as being the endpoint. I think of it as the means to build relationships with incredible women who have been in this work for decades and decades, practicing illegal abortions in the 60s. For me, art is a way to do politics, however insufficient. It is an imperfect way, but it is a way”.

To Winant, this body of images – coming from different sources, yet feeling as one – is a direct response to the way anti-abortion agitators weaponize pictures. “In the United States we assist to a lot of right-wing propaganda making use of gory photographs of aborted fetuses, blown up really big. I've thought for a long time about how to counteract that. What is the opposite of this use of photography? How might we use pictures?”, she asks. “For me, representing the abortion care workers was a way to think about how to use images as a tool of political advocacy”.

As we flip through the pages, we will probably not notice that among the bulk of archival pictures are photographs taken by Winant herself – in a way, it is a first time in her practice. “It was only towards the end of this project that I started to make my own photographs inside of the clinics. I'm always trying to deny my presence in the work, to de-center myself. But here, I tried to confront the fact that I'm in the story”, she says. “I've inherited rights from these women, I've had an abortion that was legal and safe. I am here, in the clinics and the archives, making editorial decisions on how to tell the story. I wanted to acknowledge my inheritance, politically speaking, as well as my presence in a larger narrative arc. At the same time, I really wanted to demonstrate that this doesn’t only belong to the archive. It is happening in the present tense as these women are going to work every day. They’re at work right now”.

--------------

The Last Safe Abortion is published by SPBH Editions (imprint of MACK)

Spiral bound flexicover

30.5 x 22 cm, 172 pages

--------------

All images © Carmen Winant

--------------

Carmen Winant (San Francisco, 1983) is an artist and the Roy Lichtenstein Chair of Studio Art at the Ohio State University; her work utilizes installation and collage strategies to examine feminist modes of survival and revolt. Winant’s recent projects have been shown at the Museum of Modern Art, Sculpture Center, Wexner Center of the Arts, the Cleveland Museum of Art, The Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, and as part of the CONTACT Photography Festival, which mounted twenty-six of her billboards across Canada. Winant’s recent artist’s books include My Birth (2018) and Notes on Fundamental Joy (2019). She is a mother to her two sons, Carlo and Rafa, whom she shares with her partner Luke Stettner.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based in Italy. Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.