Photobook Review: Inspiration by Matilde Søes Rasmussen

-

Published28 Jan 2026

-

Author

Audrey Munson was America’s first great model. She posed for statues, she starred in films, she was committed to an asylum, and that’s where she died at the age of 104, meeting the tragic fate that seems to be a condition of muse-hood.

In Inspiration, Matilde Søes Rasmussen (a ‘nearly-retired model’ herself) goes to New York to research Munson’s life, to see the statues and monuments that bear her likeness, and to see if she can replicate that likeness with contemporary models.

The images of the models, their portraits and poses that mirror those of the statues that still adorn New York City streets, form the visual basis of the book. As with her brilliant first book, Unprofessional, text plays a vital part, her direct and irreverent writing style is directed to asking questions about modelling, about the ethics of representation, and about photography and life itself.

What does it mean to photograph?, she asks. What does it mean to model?, she wonders. What does it mean to be objectified? And what happens when you enjoy it?

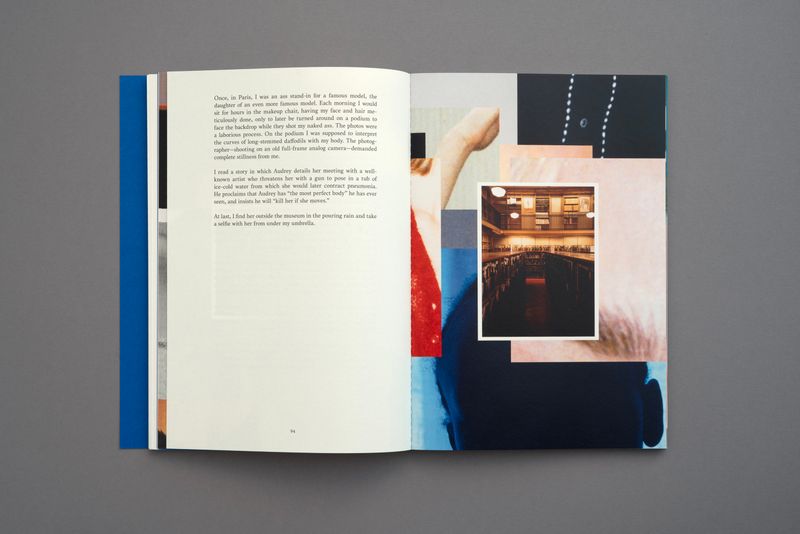

It’s a book where the uncomfortable truths of photography are never far from the surface. ‘In an interview with a photography magazine,’ she writes, ‘I’m asked if my purpose is to “take back power” by standing on the opposite side of the lens. I reply by asking if you can question objectification by objectifying?

My own diagnosis is clear. Photographer’s guilt.”

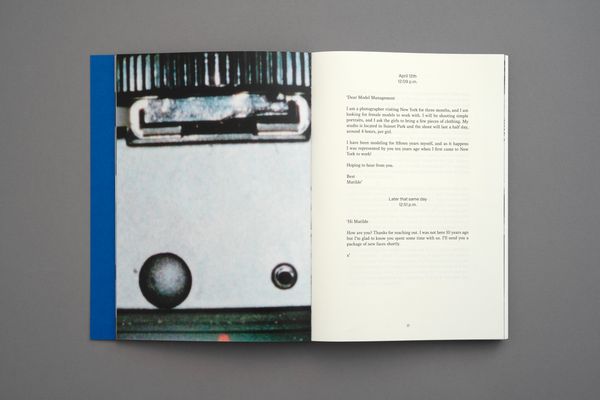

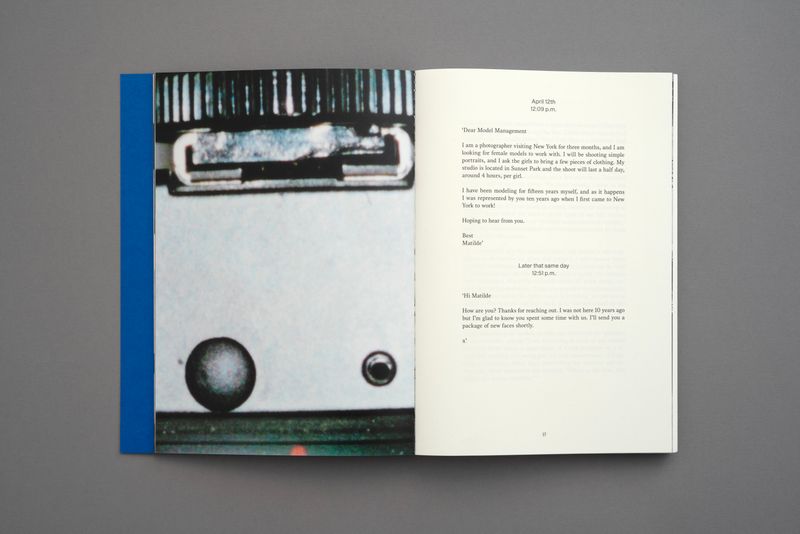

Inspiration begins in New York with a message in her inbox presenting her with ‘a gift of human girls’; these are images of models sent by an agency who will form the visual element of the book.

‘The models were paid nothing for their participation in the project,’ Rasmussen tells me in an email exchange, ‘except for pictures for their portfolio and a signed copy of the book. This is the typical deal of the industry: you shoot for free and get photos for your portfolio.

I was, of course, uncertain if I should partake in this “tradition” - as I see many reasons to doubt and critique this method practiced by the modeling agencies - and I am still not sure if choosing to work with them under those circumstances was the right choice (hence the guilt!). The choice was to shoot them without monetary compensation (as I had none) or not to shoot them at all.

And someplace in myself, I must have believed that it could be a giving experience for them as well - meeting someone who used to be in their shoes, providing them with a safe and caring shooting experience, or at the very least making some beautiful pictures for them that could help their careers (“who am I to stop a girl from pursuing her dreams?”).’

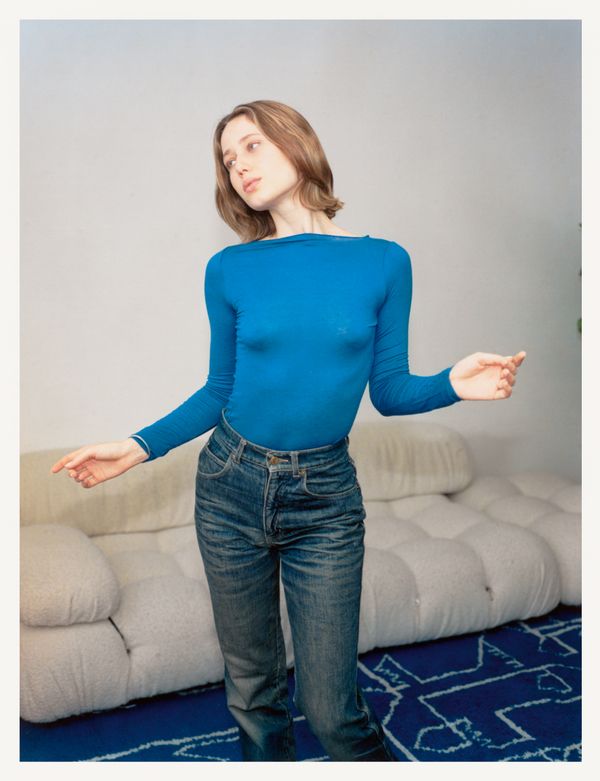

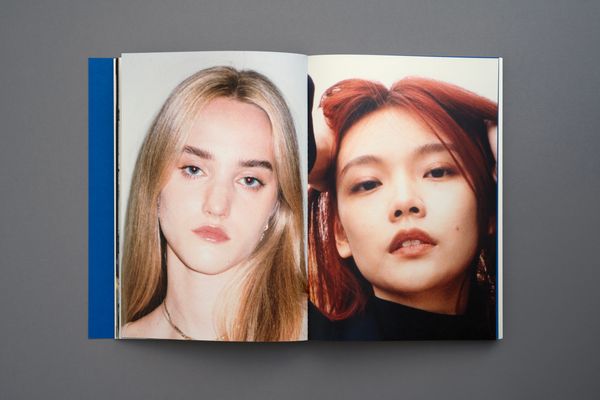

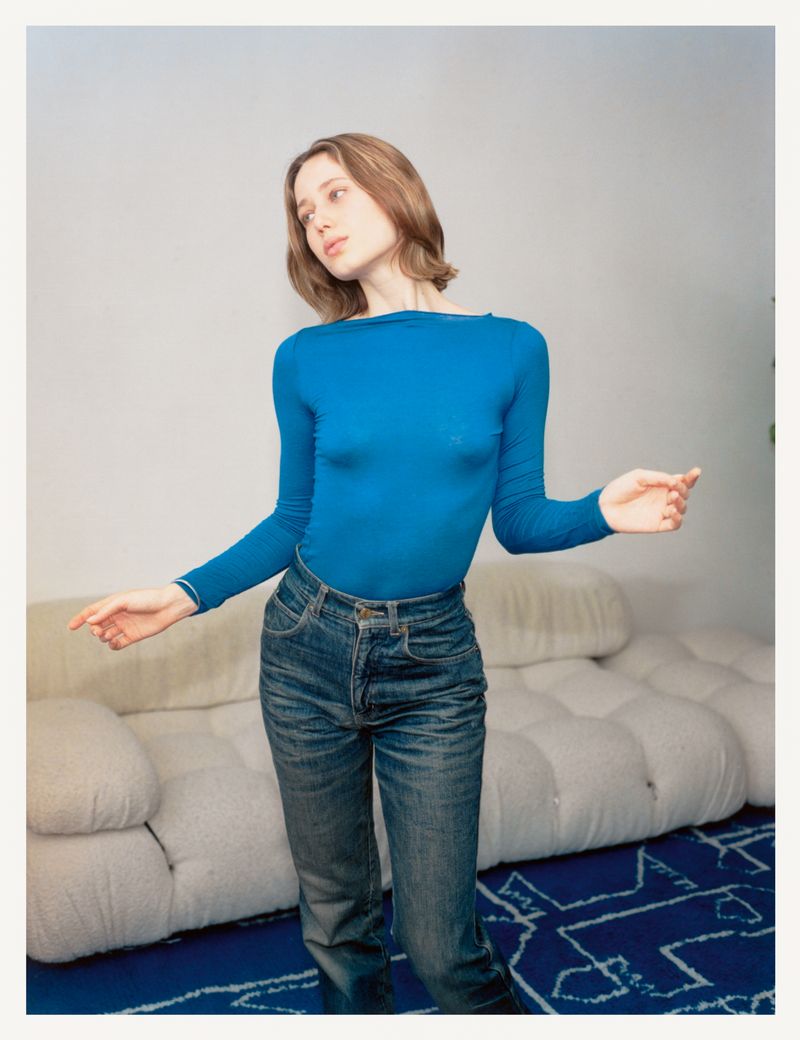

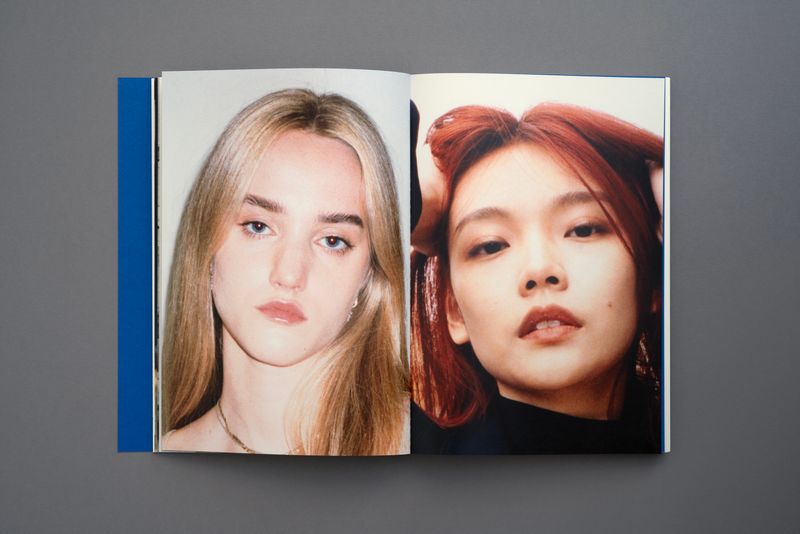

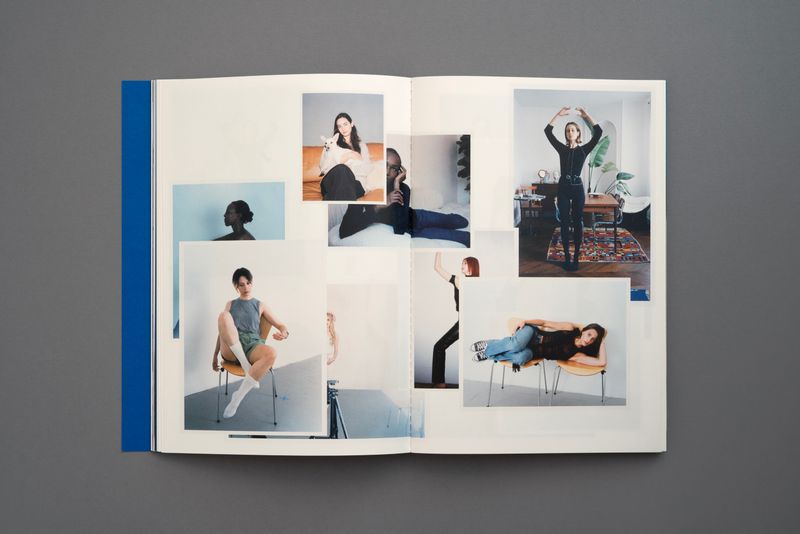

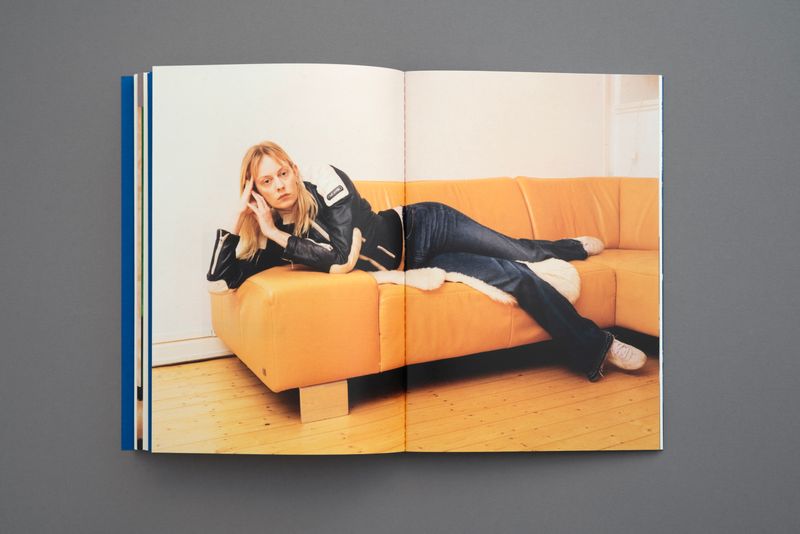

Back to the book, where we see Munson’s face and image in monuments on New York streets that bear her likeness, and crowds of people walking by. Then we see the faces of the models that will pose for Rasmussen, and then in chapters we see the models’ efforts as they replicate the Munson poses in the living room of Rasmussen’s temporary accommodation.

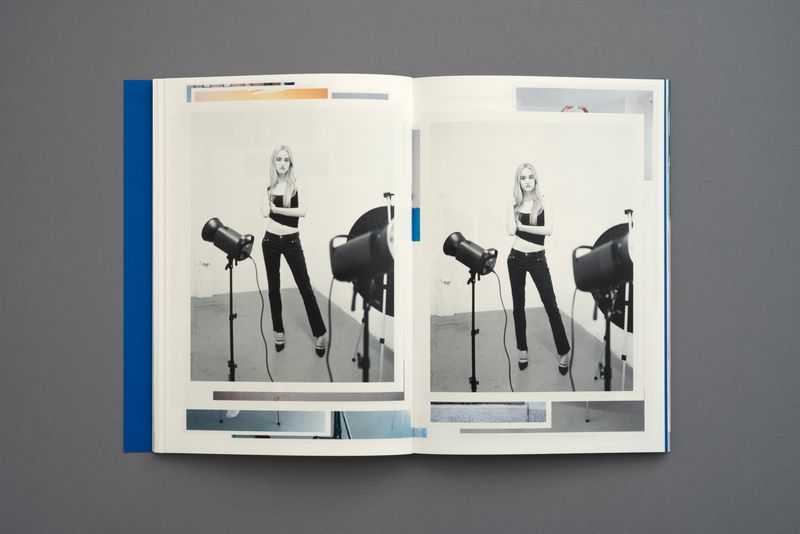

They raise their arms above their heads in homage to the Star Maiden statue, they sit cross legged on kitchen chairs, they lie down, and they stand in profile. Again and again and again. Rasmussen asks them to pose less we learn from the text, and the images of her efforts are repeated again and again on the page till they become a pile of images, one on top of the other. What is it like to be a model? What is it like to be a photographer? What does it mean to be like Munson and have ‘presence’, what is it that made her America’s “first supermodel”?

As she photographs the young models, she wonders about her own career. Why do it? Why put yourself through it? “Comedians and models,” she writes, “share the same kind of self-hatred. Working hard to get some strangers to like them?”

On May 4th, Rasmussen slips into her own modelling career. She does polaroids for her agency. It takes her two days and afterwards she ‘feels like shit’. She posts the photos. ‘Never enough likes, never from the right people… My agency replies that I look stunning. I smile from my fetal position in the bed.’

Her words conflate with the images. We start reading self-doubt into the models’ faces, we project Rasmussen’s words into their young souls as they pose for the camera; the images repeat, forming layer upon layer, as a new pose takes centre stage.

Rasmussen wonders about who’s in the picture, she questions how the picture was made. Does the photographer-model relationship matter at all and what does intimacy mean in a photograph?, she asks. ‘I’m reminded of a photographer I know who confuses nudity with intimacy,’ she writes.

More pictures appear, there’s a double page spread of two identical images of a model standing in front of the studio lighting, her left hand tucked into the elbow of her right arm, her right arm on her right shoulder.

She writes about her feelings for the models, her hopes that she can give them something through her images, her hopes that one, who ‘…isn’t just beautiful, but like, really beautiful’ will make it.

Rasmussen wonders how it is that she has seen so many pictures and statues of Munson but still she doesn’t recognise her. Does this say something about the ideals of female beauty in the West, its obsession with height and weight, and measurement? Does it say something about how men view women, does it say something about photography and modelling and the way that we see the world? You betcha!

More images follow, details of fingers, foreheads, and cleavage layered one on top of the other, and then Rasmussen goes into the archive.

The models fade now, they become blurry backgrounds as images of library stacks and statues appear. What goes into the archive determines history, we know. And what stays out is also a choice and there are people who make those decisions and people who don’t.

Now Rasmussen puts herself into the picture, posing with a friend for the Firemen’s Memorial statue. A gallerist visits her. “It’s interesting that you critique this kind of photography, yet you still fall into the same trap of the beautiful image, the beautiful girl,” he tells her. “Yeah”, she replies.

The book ends with images of Rasmussen’s poses. She scans her New York negatives and realises that ‘I have forgotten most of the sessions, mixing up faces and information. I can see how some of the girls found it awkward to maintain a certain pose… they have become half poses, half photographs, uncertain of where they are going. I am annoyed at my apparent incapability of looking past the perfect image.’

‘What is the trade-off of photographing another person?’ Rasmussen asks in her correspondence with me. ‘Or, more aggressively, what does it mean to thingify another? Are there levels to it - or is objectification bad per definition? Those are the essential questions I tried to pursue with the book.’

--------------

Inspiration by Matilde Søes Rasmussen is published by XYZ Books

2025

XYZ Books

168 pages

24 x 16,5 cm

Softcover

First Edition

Edition of 500 copies

ISBN 978-989-35169-6-6

--------------

All images © Matilde Søes Rasmussen

--------------

After working as a fashion model for 15 years, Matilde Søes Rasmussen's practice examines the commodification of the human body, often with her own body positioned in front of, beside, or behind the camera. Her work exists as a hybrid between literature and visual art, with a special interest in publications. Through text, she investigates photography’s and the photographer’s dominance over the model and, having stood on both sides of the camera, what it means to continue this ritual in her own work. In 2021, Rasmussen published her first book, Unprofessional, with the Copenhagen-based publisher Disko Bay, and was nominated for a Photo-Text Book Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles. In 2025, she published her second book, Inspiration, with the Lisbon-based publisher XYZ Books.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer, and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in person workshops begin in April 2026. More information here. Follow him on Instagram.