An Incomplete Guide To Ecological Thinking In Photographic Practice | Vol. 1

-

Published5 Mar 2025

-

Author

Mathieu Asselin, Lucas Leffler, Benedetta Casagrande, Jolene Mok and Matthew Brandt speak of the connections between photography and the climate crisis, trying to collectively answer one question: what can we do to imagine more ecological practices?

This article is part of an editorial series published in collaboration with MPB, Europe’s top camera reseller and its first to publish reports on their environmental and social impact. Aiming to open up the world of visual storytelling in a way that’s good for people and planet, MPB strives to be as circular and renewable as possible, promote inclusivity and diversity and be the most trusted and ethical reseller out there.

Photography extends far beyond the image. It is a process, and the many physical shapes it takes along the way. The first photograph taken by Nicéphore Niépce in 1827 was etched in the bitumen of Judea - a naturally occurring asphalt from the Dead Sea. Since then, copper, silver, animal gelatin, and rare earths have been a few of the many resources extracted to help make a photographic image come to the surface.

In light of the climate crisis, focusing on photography as a material process is a pressing concern. We turned to photographers and visual artists whose practice engages with ecological thinking and asked them about their methods. The effort towards more sustainable practices is articulated, slow, and, most of all, collective. Here are some glimpses of approaches and techniques that can help us re-think the way we make images.

“In today’s context of ecological urgency, we need to ask: what is truly needed from documentary photography?”: Mathieu Asselin’s inquiry into Dieselgate, using carbon-negative inks derived from air pollution

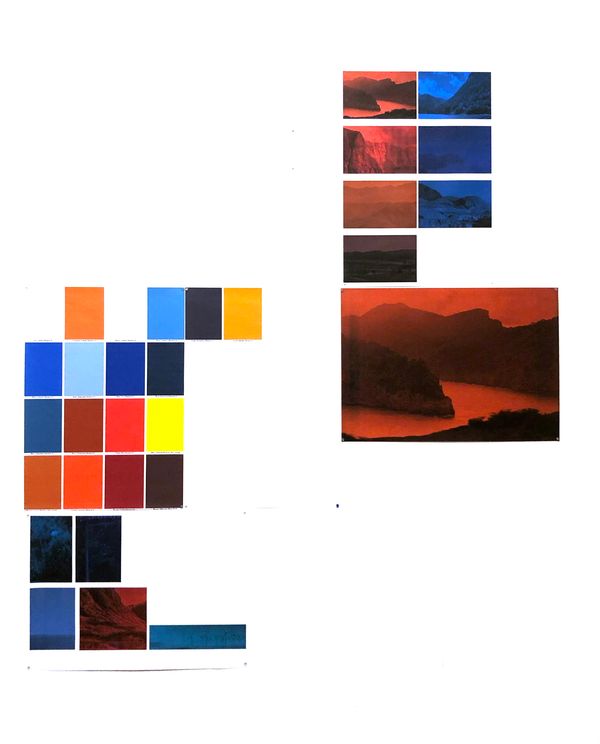

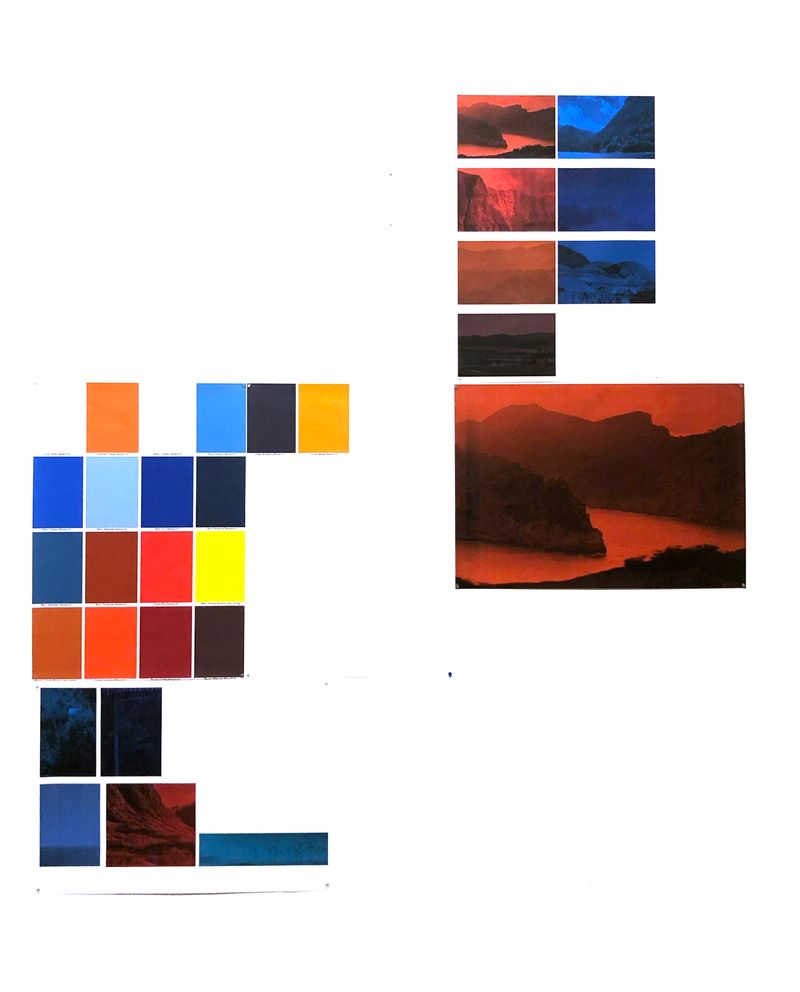

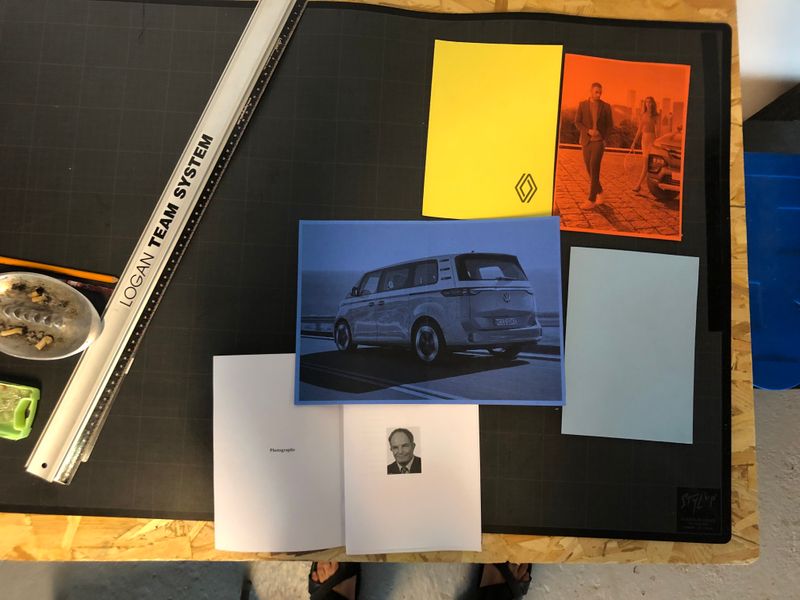

True Colors by Mathieu Asselin starts off with the Dieselgate scandal. In 2014, several car companies were found to use deceptive software to manipulate pollutant emission tests, hence minimizing the scale of their massive ecological impact. “The challenge was to represent the invisibility of the issue”, says Asselin. “I wanted to develop a visual language that could reveal both the banality and the brutality of corporate misconduct, but also how multinationals can reshape ecological facts and their narratives”.

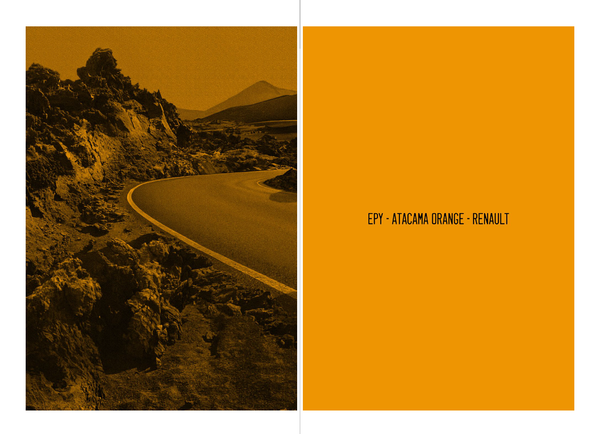

Asselin extracted unspoiled landscapes as pictured in car advertisements, and printed them using carbon-negative inks derived from car emissions. The inks, produced by an MIT team that extracted dust from diesel vehicle exhaust pipes, are a direct result of air pollution. “The process took some time to get 100% right: the negative ink was screen-printed onto metal plates painted with water-based car paint. One of the key challenges we faced was maintaining the stability of the matte black ink on top of the glossy paint without applying a clear coat, to preserve the matte texture over the glossy surface”, says Asselin. The resulting colors, with names like Blue Glacier, Orange Atacama, and Coral Red, reference the language of commercials that readily appropriates the ecosystems it destroys.

True Colors critically reflects on the role photography plays in the climate crisis. Yet, Asselin does not focus on the industry’s physical footprint as much as on its complicity in "promoting consumerism and corporate narratives”, he says. “In today’s context of ecological urgency, we need to ask: what is truly needed from documentary photography? Are we going to stick with the old narratives of ecological disaster — neutral, focused solely on consequences — or do we need more radical approaches that address where these problems come from, who is responsible, and how they operate? So yes, less environmentally harmful practices are possible, but the bigger question is how photography can critique the systems that drive ecological collapse”.

“A more organic approach to photography”: Lucas Leffler’s mud prints and defective screens

Lucas Leffler’s work Zilverbeek addresses the story of Gevaert, a photographic factory in Belgium, which accidentally disposed of silver in the nearby creek of Grensbeek in the 1920s. Leffler searches for its material traces and creates mud prints where the history of pollution is physically integrated in the image. “With this project, I began exploring what is now referred to as alternative photographic processes”, Leffler says. “These practices started gaining traction in the early 2010s as a reaction to the widespread adoption of digital tools. Interestingly, it was the same digital tools— for example through online communities—that facilitated an interest in older techniques. My work contributes to this border movement, seeking to integrate natural elements into the image and develop a more organic approach”.

Even though alternative darkroom techniques are not always fully ecological, Leffler says, their physicality fosters a more conscious relationship with the medium. “I believe alternative processes encourage a certain sobriety in image-making and printing. Toxicity is something you can sense and become conscious of during the process. This awareness inevitably shapes the practice".

Another work by Leffler, Implosion, re-purposes defective iPhone LCD screens, using them as a print base surface. “These broken screens lend themselves well to the ambrotype photographic process, which historically used black glass or iron plates. The image I printed depicts the implosion of Kodak’s building in 2007 due to bankruptcy—the same year Apple launched the first iPhone. This moment in history is symbolically rich, highlighting industrial obsolescence and its connection to the photographic medium”. “Reflecting on the environmental impact of the software we use, the websites we visit, and the digital tools we consume should be considered just as, if not more, important than addressing our physical waste”, he adds.

“All the creatures in the work are born from the same materials”: Benedetta Casagrande’s silver extraction process turning darkroom fixer into ceramic glaze

Benedetta Casagrande’s project All Things Laid Dormant reflects how we encounter other species. Photographs of animals taken across museums, aquariums, and zoos exist alongside sculptures coated in silver. It is the same silver that her analog photographs generated as a byproduct: “Having worked with black and white film, I participate in the histories of silver mining and extraction”, says Casagrande. “Silver is also one of the most polluting elements in darkroom chemistry, and the reason why fixers cannot be thrown down the drain. This is how my sculptures first came into being: I began to learn how to extract silver from exhausted darkroom fixer to re-employ it within the glazes used to finish the sculptures. I love the idea that all the creatures in the work are born from the same materials”.

How does silver extraction work? “I began by trying metal replacement: you put a metal sponge into the exhausted fixer, and if the process works, in a few hours you should start seeing the liquid darken: it means it is releasing the silver. After 24 hours you filter the solution with coffee filters and let them dry. Once dried, you burn them, and you are left with a chunk of solid silver. That was a problem for me, as I needed it in powder form so that I could mix it with the ceramic glaze. At that point I turned to Hannah Fletcher, founder of The Sustainable Darkroom, who advised me to extract via precipitation, which leaves you directly with silver particles. Overall, these methodologies are based on trial and error, and sometimes happy mistakes - for instance, with one of the batches I messed with the metal sponge and ended up with both silver and iron oxide, which gave a lovely rusty-reddish tint to the ceramic glaze”.

Speaking of sustainable darkroom practices more broadly, Casagrande notes those are based on "small choices you make every day." She explains: "For example, to make plant-based developer you can forage the plant matter, or you can buy it packaged in plastic. You can get new teabags, or you can save your used ones. To work more sustainably one has to develop an ecological way of thinking, which is something you train in time and that is hardly ever circumscribed only to the practice of art." "I do not believe that any single art practice can have any ground-breaking impact", she adds, "but I do profoundly believe that art practices, as a whole, provide an important, fertile ground. I think this is the most meaningful service that we can offer to others and to society: not our finished artworks, but new modalities of thought and being”.

“Rocks, dead honeybees, dust for pigment”: Matthew Brandt’s cyclical practice of material transformation

Collecting items that are no longer needed and finding them a purpose is vital to Matthew Brandt’s creative process. He lists “rocks, dead honeybees, dust for pigment, old chandeliers, or any number of found objects others might discard”. The idea of alchemy as matter that mutates, becoming something else, is central too. “Like the classic thought of turning lead into gold”, he says, “it’s about starting with one thing and transforming it into something entirely new”.

The result of the two impulses - re-use, and transformation - is a practice where “materials somehow come full circle, connecting back to their origins”, he says. One example is Woodblocks, a project where “carved woodblocks were repurposed at every stage: the wood shavings were turned into paper, and after printing, the same blocks were cut up and used as frames to display the work.”

This same cyclical approach informs his chromogenic color photography, where the landscape’s physical matter comes to chemically interact with the image. “In my series Lakes and Reservoirs, Waianae, and Vatnajökull, each print undergoes a treatment tied to the subject it depicts: for example, a photograph of a lake is submerged in water collected from that lake, a tropical forest image is buried in the soil nearby, and a glacier photograph is exposed to heat. These interactions create a direct relationship between the photograph and its environment, transforming the prints into relics of the process”.

“I try my best to minimize waste in my practice, but there’s always room for improvement", he says. "For example, over several years, I saved the used silver from my black-and-white printing process, collecting it in jugs. I had this idea of refining and reusing it somehow, but eventually, I had to properly dispose of it because I couldn’t figure out how to make it work. It wasn’t just taking up physical space in my studio—it was taking up mental space too. I guess there’s some kind of metaphor buried in that experience. The intention was there, but it eventually dissipated. There is a tension between my idealized self and the practical realities to grapple with”.

“The people who collect the plants are the people who protect the plants”: Jolene Mok’s plant-based film developers

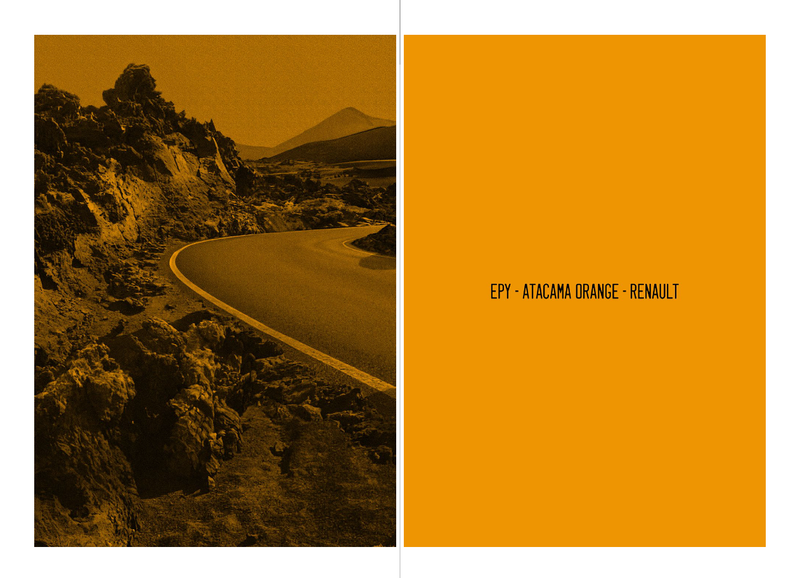

“As a head-to-toe city girl who was born and raised in Hong Kong, I always sense that nature is an alien yet sacred subject for me to handle”, says Jolene Mok. Taking botanic ecology as a departure point, Mok is working on ecological film development methods for black and white stocks. “My research deals with foraging, herbology and mycology. I wish to reconsider and rebuild my relationship with the natural world through celluloid image-making, while exploring new ecologies for this medium”, she says.

Mok’s plant-based developers are made out of polyphenols which, she explains, "are natural chemical compounds found in most plants”. “I use both store-bought bulk-dried herbs, teas and spices, as well as plants that I foraged and dried myself. First of all, I weigh how many grams of dried plants I need for the amount of film stocks I am to process. The most tricky part is that the amount of polyphenols is different in each plant, so it's always a bit of a guessing game on how many dried plants to use. For making 500ml of plant-based developer, 25g of dried plants is a fair starting point to conduct film tests. It's essentially brewing a very strong tea – so it always smells good! After steeping it for 30 minutes, I add sodium carbonate (washing soda) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C). I then use a nylon mesh bag to squeeze and string out all the plant remnants. After the plant-based solution has cooled to around 30°C, I pour it into the developing tank. Once ready, I use it like a regular developer, although the processing time is often much longer”.

Foraging plants herself is a meaningful part of Mok’s practice. “I go into a landscape looking for something that we rarely pay attention to, learning about the immediate surroundings and its flora from scratch. The mindset of mindful foragers derives from ‘the people who collect the plants are the people who protect the plants’, which is the antithesis of extractivism”, she explains.

In short: tips, thoughts and processes towards a more conscious practice

Challenge invisibility: seek visual languages that can represent less obvious impacts.

Be radical: move beyond simply documenting disaster, to instead address causes and responsibilities. Photography can be a powerful tool to expose how ecological facts are often manipulated.

Integrate natural elements: explore alternative processes to incorporate organic materials.

Conscious material use: foster a relationship with the medium by being aware of its toxicity.

Digital footprint: consider the environmental impact of digital consumption and waste.

Repurpose byproducts: extract and reuse materials generated from your process.

Small, everyday choices: remember sustainable practices are built on consistent, sometimes less remarkable action.

Beyond the finished artwork: consider that real impact is to be found in the process, and the new modalities of thought it fosters.

Direct environmental interaction: let the environment be an active subject, a participant in your images.

Plant-based processes: explore the potential of plants to reduce chemical use, while fostering a deeper, more respectful connection with nature.

Fight extractivism: engage with materials in a way that protects and preserves, rather than exploits.

--------------

About MPB

For over 10 years, MPB has made used photo and video gear more accessible. With experts in Berlin checking and individually photographing every item, MPB offers camera equipment you can trust, with a free six-month guarantee for added peace of mind.

More than half of us have a camera at home we’re not using. Find out exactly how much your kit is worth with a free instant quote from MPB. Take advantage of free, insured shopping to send in your gear, and get paid directly into your bank account.

--------------

Useful Resources

The Sustainable Darkroom: an artist-led, research community that develops low-toxicity chemistries and practices in photography.

MPB Meets Alice Cazenave: The Darkroom Innovator Making Film Photography Eco-Friendly

Alternative Processes: learning platform and community for historical, experimental and sustainable photographic processes.