Roots Of The Earth by Akshay Mahajan and Prabhakar Kamble at Jhaveri Contemporary

-

Opens10 Jul 2025

-

Ends16 Aug 2025

-

Link

- Location Mumbai, India

In Roots of the Earth, Prabhakar Kamble and Akshay Mahajan begin with what is left unspoken, foregrounding the histories of silenced majorities through acts of recovery, resistance, and reassembly.

Overview

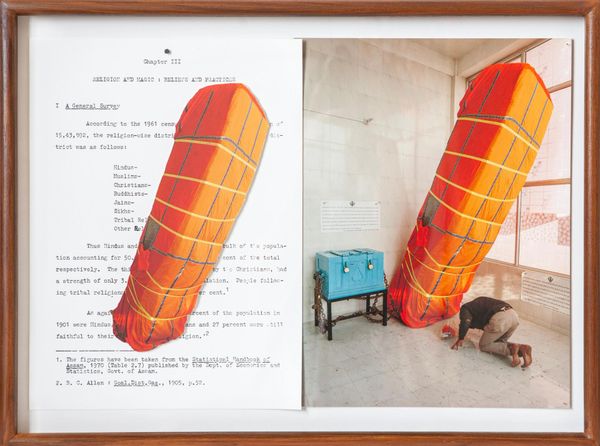

The colonial need to document and classify, at once a product of and compounded by the politics of control and prejudice, led to intentional acts of erasure. In the post-colonial moment, this classification impulse found new life: nation-building projects brazenly reinforced and omitted minor, marginalised histories to project a future hinged on ideas of development and progress. How can we think of development and emancipation without ideas of equality, inclusion, and reparation?

Prabhakar Kamble’s artistic practice is deeply tied to his work as a social organiser – an ethos that manifests in his use of vernacular materials and everyday objects, often sourced from local markets. These elements, reassembled into precarious yet potent sculptural forms, embody a belief in collective resistance and social memory. In forming solidarities and bringing people together, Kamble invokes Ambedkarite consciousness as both an intellectual position and a lived, critical, emotional awareness. He positions anti-caste work as inseparable from the struggle for radical democracy, equality, and dignity.

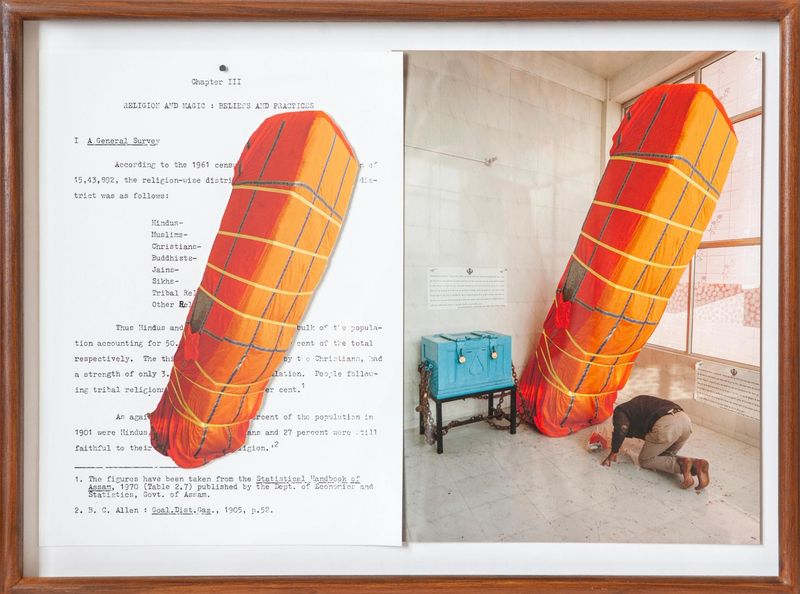

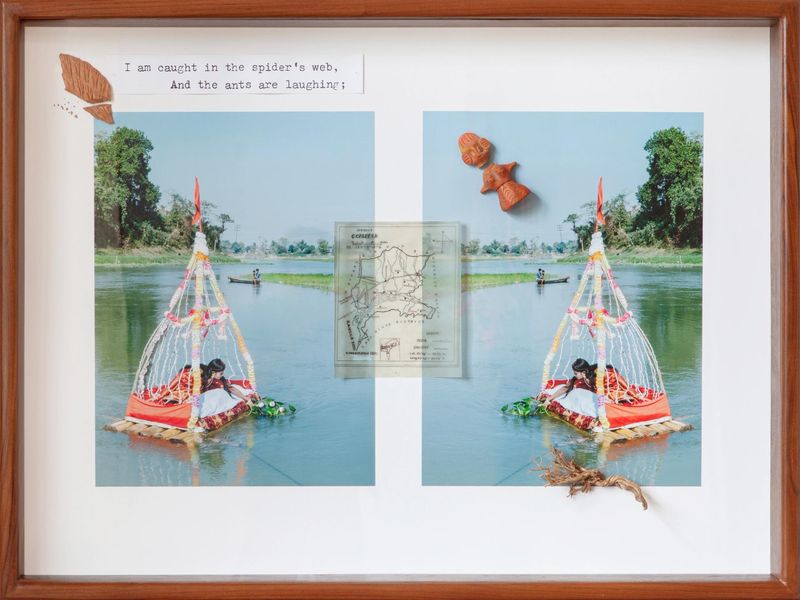

Akshay Mahajan is interested in acts of remembering and forgetting. His method is collage, not just as a formal gesture but as a way of thinking: layering song, myth, terracotta, and image into assemblages that disrupt linear time. To photograph, for him, is to bear witness as much as it is to interrupt the singularity of the archive. Not unlike Kamble, he challenges and liberates the archive from its factual impulse, delving into the fluidity of oral histories, lores, and songs to conjure, instead, a mosaic of overlapping truths and silences.

Interspersed across the gallery, the works of both artists stretch and spill, their shadows looming as they gently sway in the sea breeze or stand still. With Prabhakar’s Material Turn, 2025, a restless hum of mechanized cowbells echoes through the exhibition, reminiscent of cows as they walk, graze, and plough. Belts, ornaments, and tassels churn in a whip-like circular gesture. Kamble returned to Kolhapur in South-West Maharashtra, close to his ancestral village where he was born into a family of daily-wage labourers, to sustain a studio. The elements within his works – hook, bell, pot or rope – were collected from local bazaars and, taken together, they evoke caste experiences of violence structured in religion, customs, society, and law.

A nylon rope coils in Utarand, 2025. Snake-like, it channels through the hollows of delicately stacked earthen pots placed atop one another. Precariously balanced on a metal stand, the pots shrink in size and taper as they ascend, resembling a body perhaps or a mountain. Resting atop like a quiet guardian is an elephant dusted in powdered indigo blue. Perched delicately yet resolute, it holds within it a convergence of symbols: the weight of Ambedkarite blue, symbolic of equality, the spiritual memory of Buddhism, and the spectral presence of resistance shaped through stillness. A bouquet of iron hooks, dangling low in the stand’s base ring, seemingly weighs the sculpture into place.

Kamble primes his sculptures with references. Rope, grey and frayed at its edges, directly connote bondage and manual labour – acts of binding, tethering, pulling, and hauling, all associated with a range of caste occupations. Rope is used to tie and lower men into toxic sewers or wells. It also calls to mind the many young lives lost to suicide, a result of institutional discrimination and bullying. The matkas or pots in Kamble’s sculptures are a reference to water but also to the urns used to collect the remains of those lost to violence.

In the series Chandelier, 2025, within suspended masses of neon ropes, braided shells and pots, there are cowbell chimes to remind us of the proliferation of images and videos of men tied and paraded for tanning carcasses or suspicions of carrying meat in recent years. This public humiliation has been consistent across time, used to ‘discipline’ lower castes for transgressing caste codes like drawing water or drinking water from a well or a pond designated for the use of upper castes. In recent years, it has accelerated into hate-fueled violence and lynching.

Spread across an entire wall of the main gallery, Akshay Mahajan’s People of Clay (Crows bring rain), 2025, reads like an association diagram of another kind of erasure. His subject – and his muse – is the place of Assam’s Goalpara district along the Brahmaputra, where Assam and Bangladesh are divided by colonial lines. In Mahajan’s hands, and indeed through his lens, this landscape is reconstructed in layers, its stories and legends distilled into texts, images, and objects. We are offered an emotional cartography of a place built from a sense of belonging and care, love perhaps. People of Clay, mirrors, also, this artist’s interest in materials and the histories they harbour, touched by hand and/or textured by time. Here, a simple object of function or play contains within it the essence of the people that made it or cherished it. The terracotta village Asharikandi, for example, uses riverine silt shaped into Hatima dolls by women. Each toy is enlivened by touch and breath. The unspoken passing of tradition or skill through generations, or the gently whispered rumour, challenges the need and pressure to date, classify and/or structure everything. Even when the existence of this community was kept out of official records, they slipped through the cracks. Sometimes they chose to render themselves invisible, quietly surviving in the corners of the mind, homes, and landscapes. Here they developed – breathing, fermenting, evolving – a veritable lived history nonetheless.

An aspect of this history is the legend of the Behula, whose husband Lakhamindra dies of snake bite, a consequence of a curse by Goddess of Snake, Manasa. He is set afloat on a raft on the river. Overcome by grief, Behula refused to leave his side and sailed the raft with his dead body. ‘Either I shall die with him or he will come to life and I shall be beside him when he does.’ Villages passed them along and people thought her mad. The corpse began to decay. Behula prayed to the Goddess who finally responded and ensured the raft survived storms, whirlpools, and crocodiles. She brought her Lakhamindra to life. In the dioramic assemblage, People of Clay (Behula and Lakhamindra), we see her, dressed in wedding finery, gently bending over her dead husband’s corpse to fetch a water hyacinth.

Mahajan and Kamble rely on and thrive in communities and in the possibilities of the histories lived and experienced. They set out to challenge rigid socio-political formations to learn, heal, and reclaim from the collective and the shared. Like the people of clay, our identities are constantly in a flux, evolving, not tied to lands and identitarian constructs.

Mario D’Souza, 2025