Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Haiti

Sexual and gender-based violence is an overlooked emergency in Haiti. Médécins Sans Frontiers has opened in Port-au-Prince the Pran Men’m Clinic, a facility offering the emergency medical assistance required during the 72 hours following an assault, along with longer-term medical care and psychological support.

Photojournalist Benedicte Kurzen travelled to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, seeking to document and showcase the domestic responses to this largely invisible crisis - sexual and gender-based assault in the country. Each portrait documents an intimate moment with girls that have experienced trauma through sexual assault. At the same time, the quietness and beauty of each portrait remind us of the resilience of each girl and the importance of not victimising them.

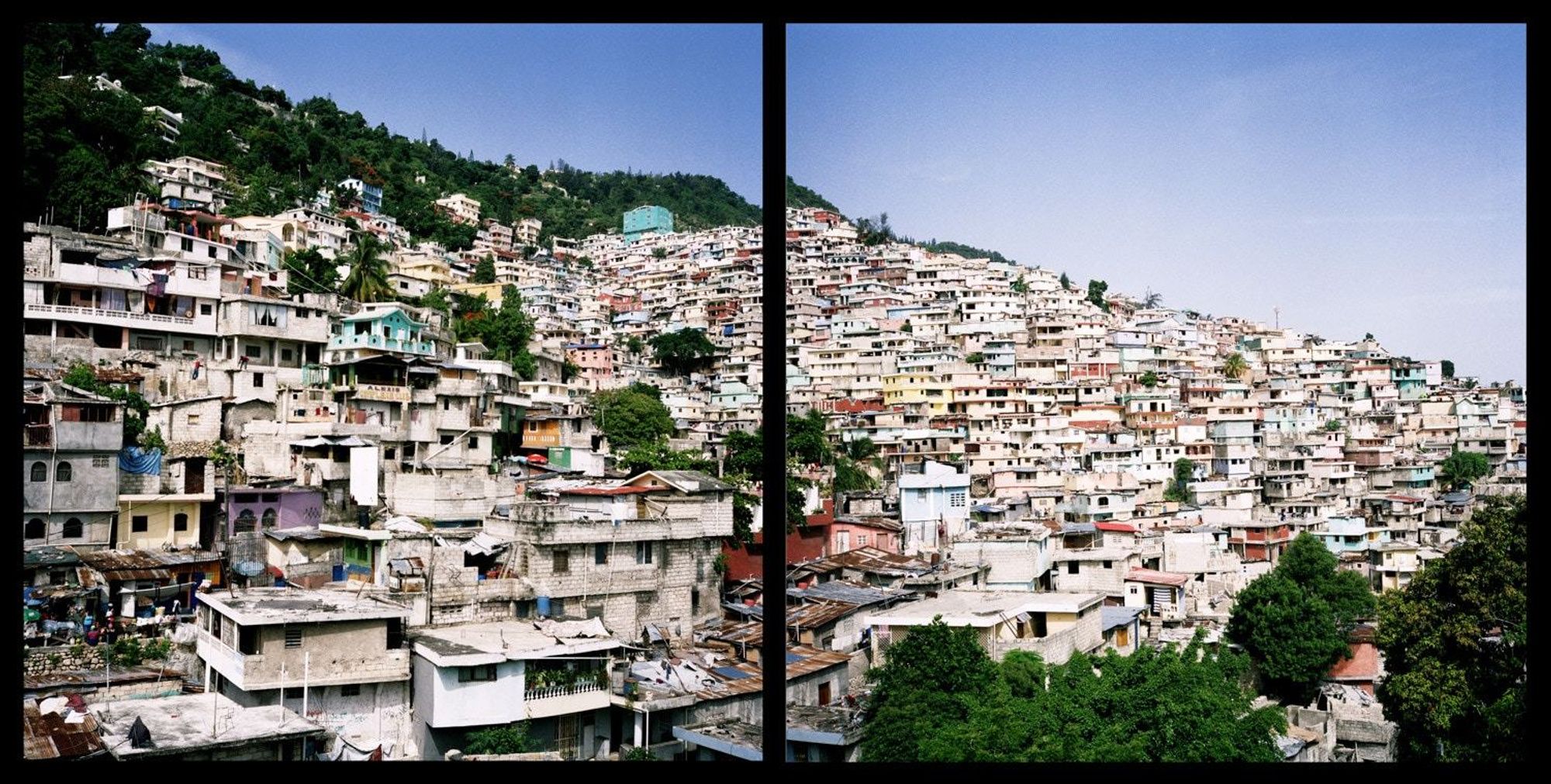

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 One of the neighborhood in Port Au Prince. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port au Prince, July 2016 GISELE, 20 years old: "My cousin told me that I had bad luck, that something was wrong with me. A friend of my parents said that he was a mason and therefore could help remove the “bad eye”. He took me to an isolated place and asked me to get naked. He touched me and raped me. I even gave him 1000 gourds. I told my family what happened. Now he is hiding, and he is under the protection of a women judge. I want justice to be done. I also know he is a recidivist. He did the same to two little girls from my neighbourhood. The parents are scared so they don’t do anything. Both girls are 15 and 12." Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port au Prince, July 2016 GISELE, 20 years old: "My cousin told me that I had bad luck, that something was wrong with me. A friend of my parents said that he was a mason and therefore could help remove the “bad eye”. He took me to an isolated place and asked me to get naked. He touched me and raped me. I even gave him 1000 gourds. I told my family what happened. Now he is hiding, and he is under the protection of a women judge. I want justice to be done. I also know he is a recidivist. He did the same to two little girls from my neighbourhood. The parents are scared so they don’t do anything. Both girls are 15 and 12." Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Source Zabeth, July 2016 Unidentified children play in the water of Source Zabeth where one of the survivor wanted to be pictured. MARIE, 21 years old (fake name): “I want to be photographed in the water. And we need drive out of Port-au-Prince. I would like to pose as someone who wash laundry with a traditional outfit. My story is a urban story. I met this guy on the street. We started to chat. After a while I told him I was looking for a job. He immediately said that one of his friend was precisely looking for someone like me. He said that he needed to go to his place to pick up some documents. When we got there he pulled out his gun. This is when it happened." Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port au Prince, July 2016 Every Friday the girls going to SOFALAM are allowed to play on the street, now some of the girls are holding the door of the coumound before going out. MSF works with a network of local organisations, who work with young girls and vulnerable children. Solidarité fanm pou yon lavi miyò (Sofalam) is one of them. They provide shelter to twelve girls, who have been refered to them by governmental social agency. Those girls are separated from their families and have been living in a extremely vulnerable situation. Sexual abuse has been identified in some case. One of the main challenge that SOFALAM faces is the lack of means to hire competent psychologist and social workers who could help children who have been victim of sexual abuse. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

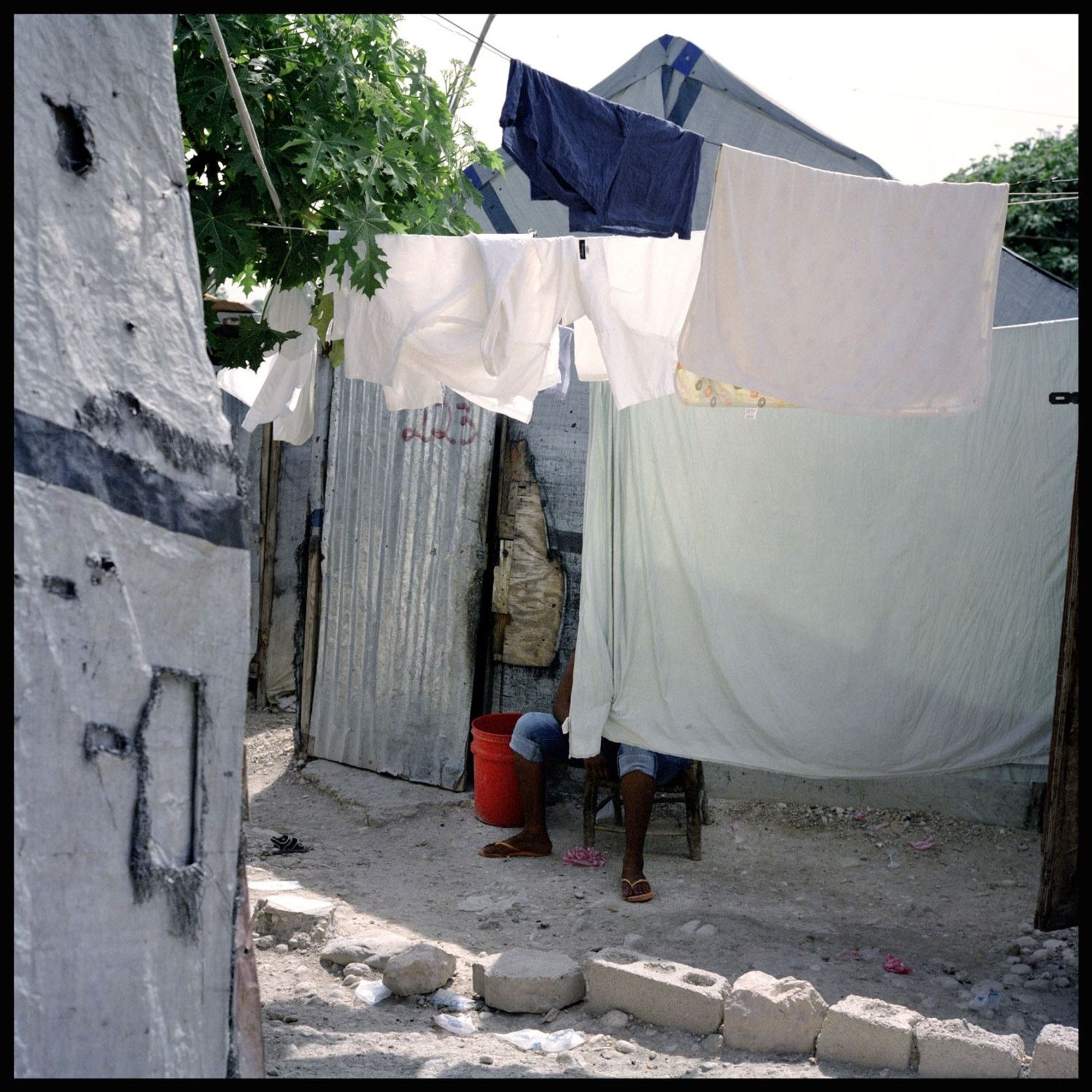

HAITI, Port au Prince, July 2016 A little girl skirt is drying in the sun. MSF works with a network of local organisations, who work with young girls and vulnerable children. Solidarité fanm pou yon lavi miyò (Sofalam) is one of them. They provide shelter to twelve girls, who have been referred to them by governmental social agency. Those girls are seperated from their families and have been living in a extremely vulnerable situations. Sexual abuse has been identified in some case. One of the main challenge that SOFALAM faces is the lack of means to hire competent psychologist and social workers who could help children who have been victim of sexual abuse. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 VIVIANE, 22 years old: “My best friend found the MSF clinic on the social network. I came straight away. The boy was a friend from school. He took me to his home, to give me one of his book - “My muse is a man”-. I kept asking if his dad was there. He said yes. When I arrived the house was empty. He took me to his room and forced me." Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Source Zabeth, July 2016 Unidentified children play in the water of Source Zabeth where one of the survivor wanted to be pictured. MARIE, 21 years old (fake name): “I want to be photographed in the water. And we need drive out of Port-au-Prince. I would like to pose as someone who wash laundry with a traditional outfit. My story is a urban story. I met this guy on the street. We started to chat. After a while I told him I was looking for a job. He immediately said that one of his friend was precisely looking for someone like me. He said that he needed to go to his place to pick up some documents. When we got there he pulled out his gun. This is when it happened." Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 JEANNE, 31, SOLANGE, 16 (fake names) "I have three children. I lived in Petionville. I was in my house and late at night, two men showed up. They raped my daughter and me. I went immediately to MSF clinic. They kept me one month there in Kai Bleue. They hit my head a lot as I wanted them to rape me but not my daughter. Ever since I have epilepsy. The Great Creator spared my life. One month later they burnt the house of my mother, to intimidate me. I have to run away, and take refuge here as my attackers are still around. They took everything. I tried to call the police when they raped me, but they took my phone away. My head is constantly hurting, so I go to the clinic twice a month." OFAVA, Oganzayon Fanm Vanyan an Aksyon, is a Port-au-Prince-based organization MSF partner with. They are working to protect the rights of Haitian women and therefore refer women and children victims of violence to one another. MSF taking care of the medical and psychological part and OFAVA provides shelter and food. After the eartquake OFAVA recieved a lot of financial support, explains Lamercie Charles-Pierre, general coordinator. For the past year their partners have withdrawn their support and the organisation can barely feed the two families they provide shelter to. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

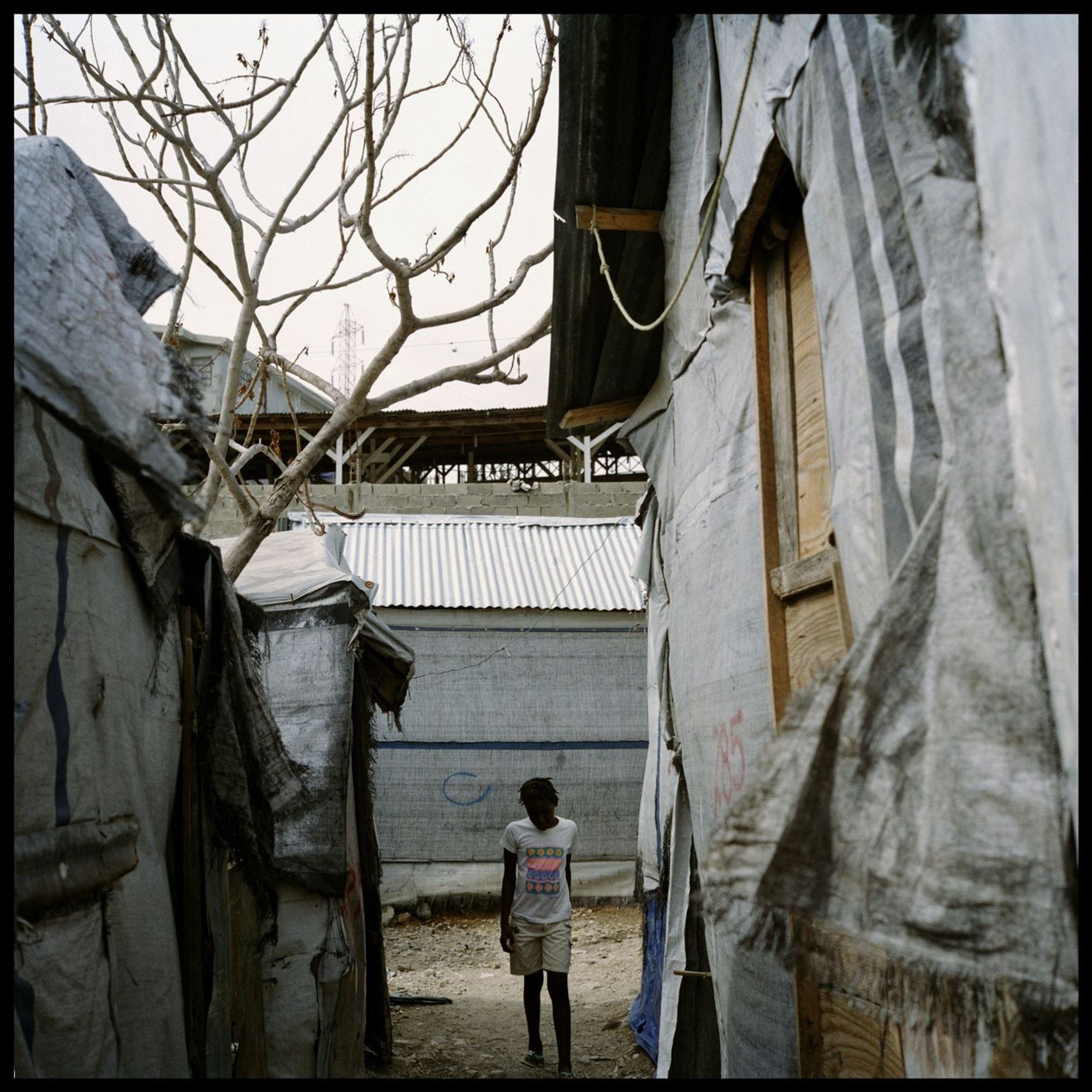

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 The Camp in Delmas. Over a million people made homeless in the 2010 earthquake in Haiti moved into refugee camps that offered little food, work, or safety.[6] The UN reported that as of October 2012 about 370,000 people were still in the camps and facing poor and insecure living conditions.[6] The earthquake directly preceded a rapid increase in the numbers of sexual violence in Haiti. Factors contributing to vulnerability after the earthquake include homelessness and losing the protection afforded by a house; losing family members who might have provided protection; and increases in levels of violence due to the stress of living in substandard conditions; and lack of legal recourse to prosecute rapists. The tent cities have little privacy, lighting, or policing. Young children are also victimized. Women who need to leave their children in search of work, food, or water sometimes have no option but to leave them alone or with strangers; sometimes these children are sexually abused. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 STEPHANIE, 52 years old (fake name): "I had a boyfriend but we were separated. He had a lot of other girlfriends and also children. I even look after one of his boy and also one of his daughters now. She is like my own. One night, he came to my place and we fought. He threw me on the floor and raped me so brutally that I started to bleed. My daughters and children don’t know what happened. I did not tell them anything. I pretended the blood was something else. After a couple of days, I decided to go to the MSF clinic. It is passed now, and my only worry is actually not the rape, it is to become blind; I have eyes problem. If I can’t see anymore, I can’t help my family anymore. This worries me a lot." Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 Typical haitian tap tap are gaily painted buses or pick up trucks that serve as share taxis in Haiti. They are usually covered with lavish decoration featuring religious slogans, famous people, or voodoo symbols. Like every public transports it is also a place were woman are vulnerable. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016. VIVIANE, 22 years old: “My best friend found the MSF clinic on the social network. I came straight away. The boy was a friend from school. He took me to his home, to give me one of his book - “My muse is a man”-. I kept asking if his dad was there. He said yes. When I arrived the house was empty. He took me to his room and forced me. Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016. SARAH, 13 years old The mother of Sarah: “He is someone we knew. He lived in the same area than us in the camp. Now he is nowhere to be found. Our tent was broken and had a big hole in it. he came through it. He rape Sarah. She was on her own. Sarah wants to dance, she loves it but I don’t want her to. I feel she is too visible when she dances. Now she stays most of the time with my nieces.” Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

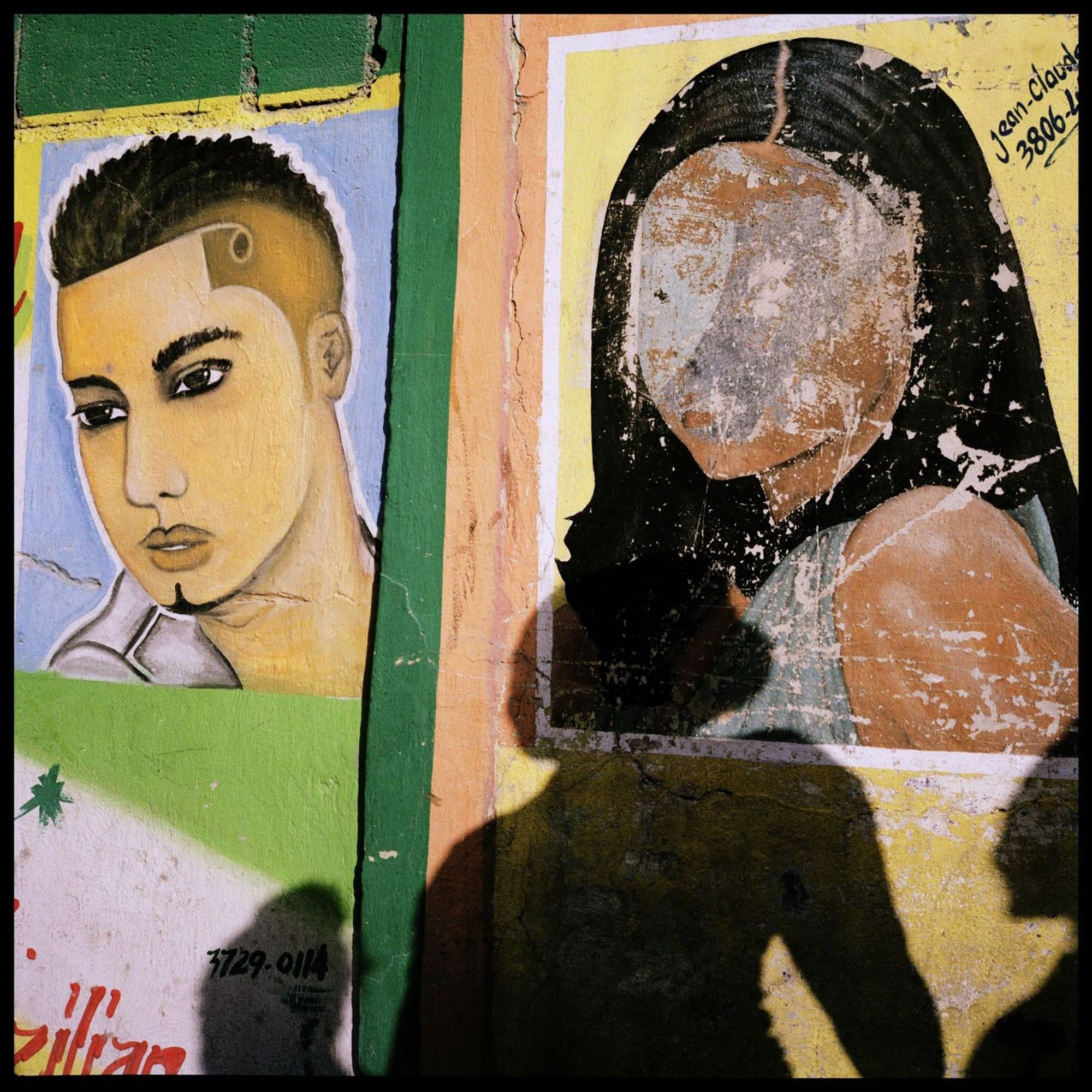

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 Advertising for a beauty salon in the streets of Croix de bouquet. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016 The premises of OFAVA, Oganzayon Fanm Vanyan an Aksyon. Because of the lack of funding the project had to be abandoned. OFAVA is a Port-au-Prince-based organization MSF partner with. They are working to protect the rights of Haitian women and therefore refer women and children victims of violence to one another. MSF taking care of the medical and psychological part and OFAVA provides shelter and food. After the eartquake OFAVA recieved a lot of financial support, explains Lamercie Charles-Pierre, general coordinator. For the past year their partners have withdrawn their support and the organisation can barely feed the two families they provide shelter to. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016. The Camp in Delmas. Over a million people made homeless in the 2010 earthquake in Haiti moved into refugee camps that offered little food, work, or safety.[6] The UN reported that as of October 2012 about 370,000 people were still in the camps and facing poor and insecure living conditions.[6] The earthquake directly preceded a rapid increase in the numbers of sexual violence in Haiti. Factors contributing to vulnerability after the earthquake include homelessness and losing the protection afforded by a house; losing family members who might have provided protection; and increases in levels of violence due to the stress of living in substandard conditions; and lack of legal recourse to prosecute rapists. The tent cities have little privacy, lighting, or policing. Young children are also victimized. Women who need to leave their children in search of work, food, or water sometimes have no option but to leave them alone or with strangers; sometimes these children are sexually abused. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

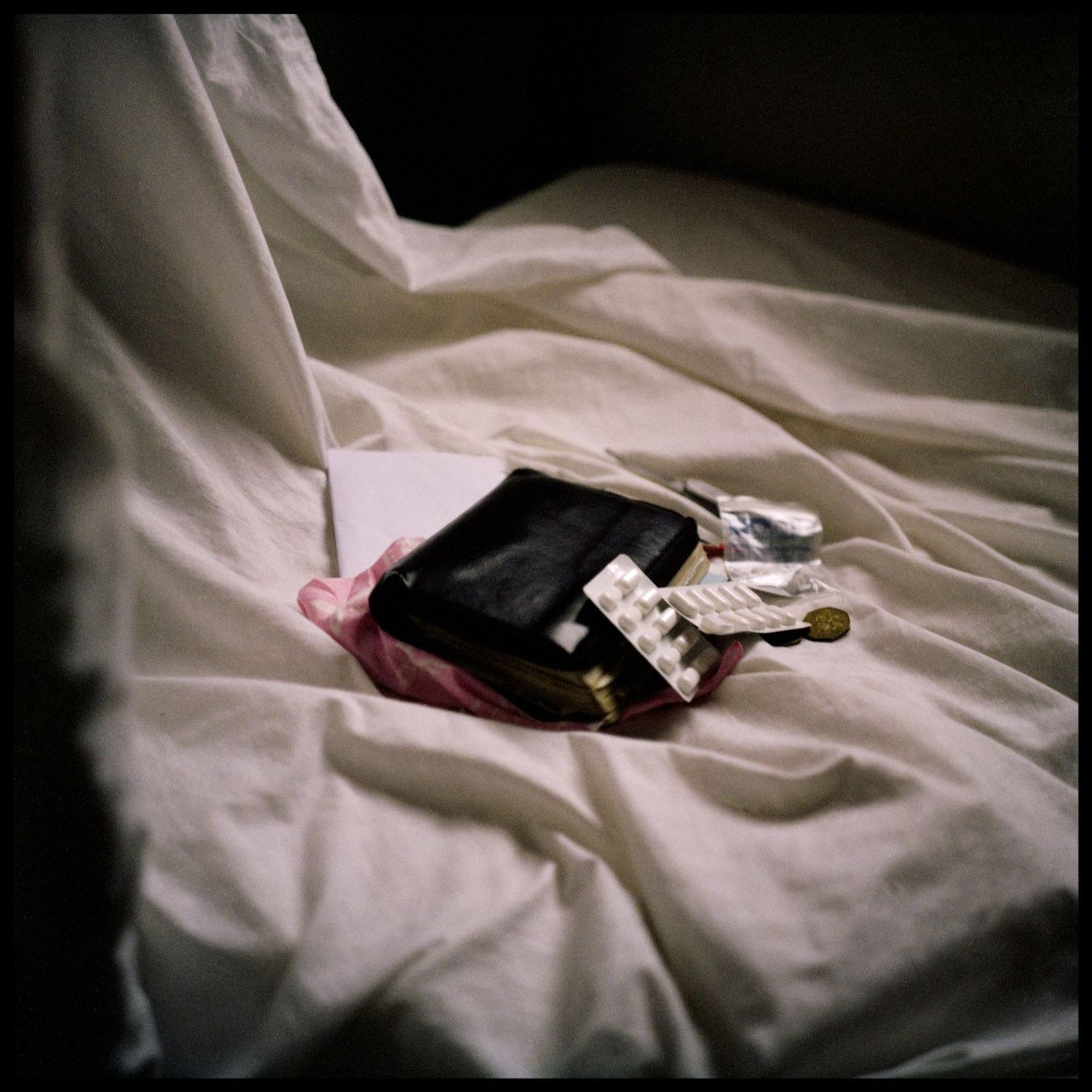

HAITI, Port-au-Prince, July 2016. Sexual violence is a medical emergency in Haiti. In the year since opening, 569 people have come to the MSF Pran Men m (Creole for “Take My Hand”) clinic in Port-au-Prince. After a recent local communications campaign, in recent months more than a hundred people a month have been coming for medical help and support on average. More than half have been under-18. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

HAITI, Port au Prince, July 2016. MSF works with a network of local organisations, who work with young girls and vulnerable children. Solidarité fanm pou yon lavi miyò (Sofalam) is one of them. They provide shelter to twelve girls, who have been refered to them by governmental social agency. Those girls are seperated from their families and have been living in a extremely vulnerable situation. Sexual abuse has been identified in some case. One of the main challenge that SOFALAM faces is the lack of means to hire competent psycologist and social workers who could help children who have been victim of sexual abuse. Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

AITI, Port au Prince, July 2016 GISELE, 20 years old: "My cousin told me that I had bad luck, that something was wrong with me. A friend of my parents said that he was a mason and therefore could help remove the “bad eye”. He took me to an isolated place and asked me to get naked. He touched me and raped me. I even gave him 1000 gourds. I told my family what happened. Now he is hiding, and he is under the protection of a women judge. I want justice to be done. I also know he is a recidivist. He did the same to two little girls from my neighbourhood. The parents are scared so they don’t do anything. Both girls are 15 and 12." Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR