The Black line

-

Dates2017 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues, Contemporary Issues, Documentary

- Location Haiti, Haiti

-

Recognition

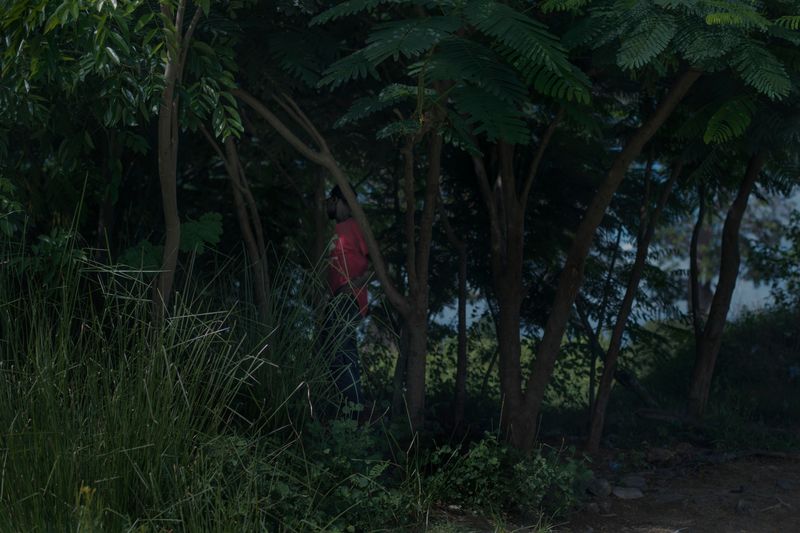

The Black Line. Eighty years after the infamous "parsley massacre" of October 1937, the shadow of injustice, stigmatization and violation of human rights still marks the border between Haiti and Dominican Republic.

Haiti and Dominican Republic are divided by 360 km of borders, 55 of which are made up of the River Massacre, in the northern region of Hispaniola.

In October 1937 its waters turned red as blood, when Rafael L. Trujillo- dictator of the DR- led one of the most infamous events in the story of the island, known as the “parsley massacre”. In a few days up to 30000 Haitians were massacred along the river by Dominican military forces and conscripted civilians with the alleged excuse that a supposed Haitian "invasion" could have posed a serious threat to Dominican society and its racial integrity.

The slaughter, which owes its name to the Spanish word “perejil” (a word that Creole speaking Haitians fail to pronounce and that was used by Dominican soldiers to recognize their victims by asking them to identify a spring of parsley), has irrevocably widened the rift between the two countries and, as a long-term effect, has radicalized a deep anti-Haitian sentiment in the whole DR, which in turn resulted in episodes of violence against Haitians.

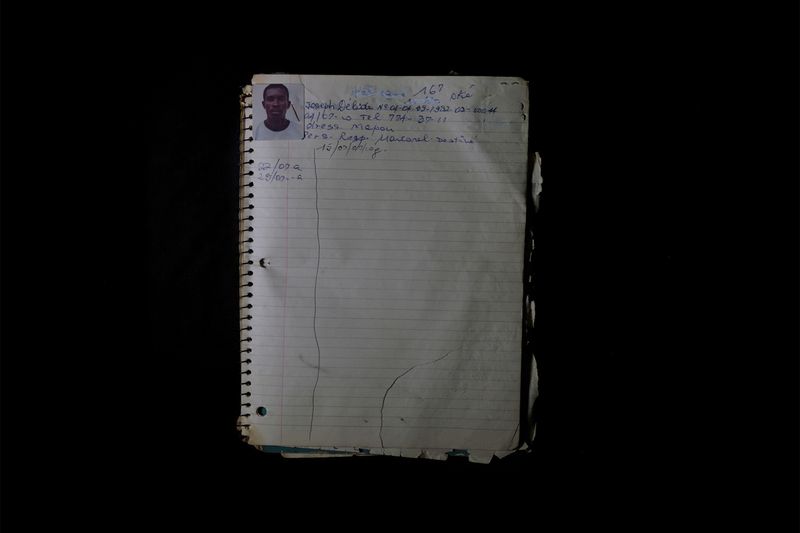

Immigrants from Haiti have been crossing the border for more than 100 years in search of a life opportunity as sugarcane or farm laborers, while the Dominican government never stopped to pursue actions of forced repatriations and a permanent policy of stigmatization against their darker-skinned neighbors.

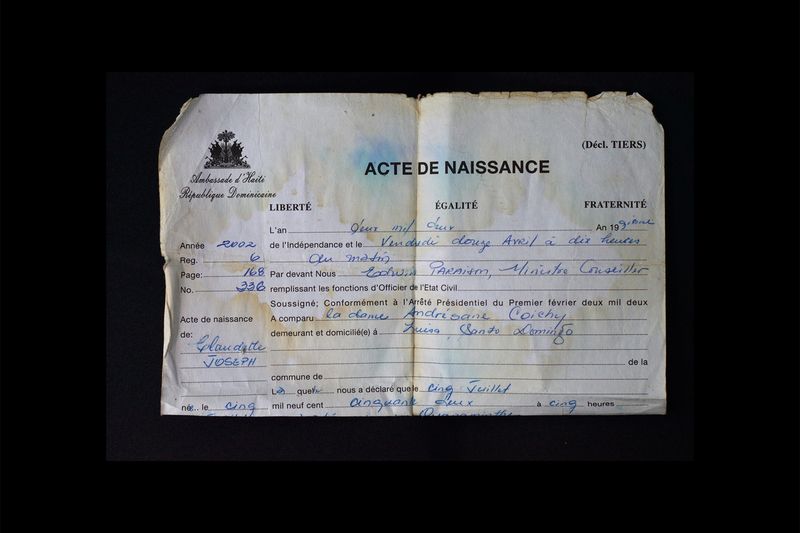

In 2013 a court ruled that people born in the DR of undocumented migrants, from 1929 onwards, had never been entitled to Dominican citizenship and should be deprived of it, giving way to countless cases of abuses against Haitians, as illegal expulsions, denial of identity documents and arbitrary deprivation of nationality.

Even though a regularization act was subsequently issued to mitigate the discriminatory effects of that sentence, this recent kind of violence towards Haiti and its blackness represented a sort of legal ethnic cleansing, replicating by judicial instruments what in the past has been done with machetes.