Nā́rī

-

Dates2019 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Punjab, Lucknow, Jaipur

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

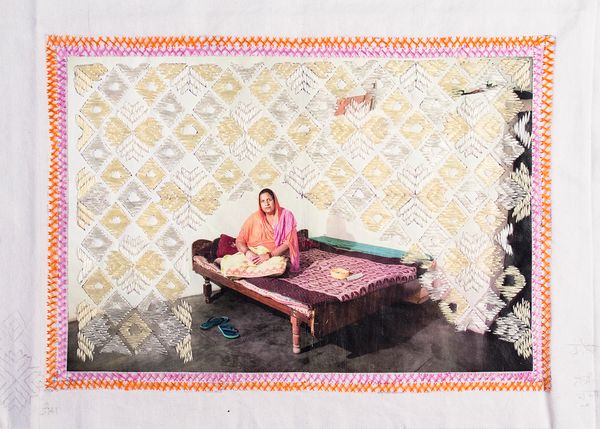

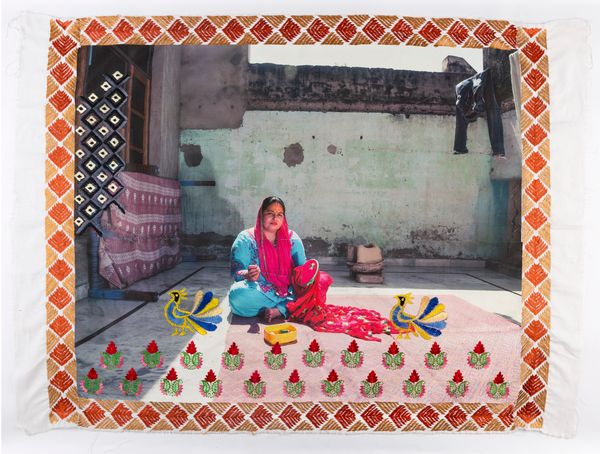

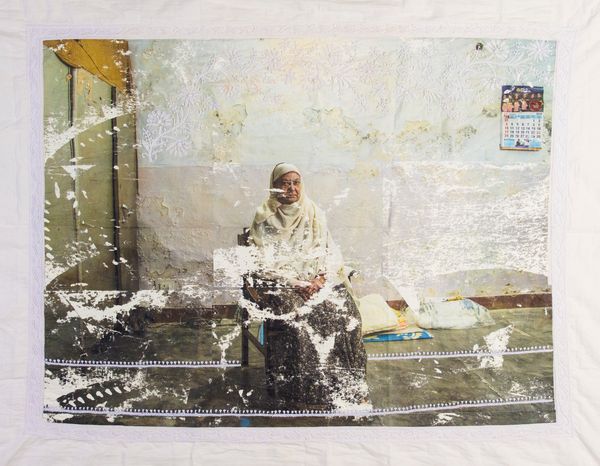

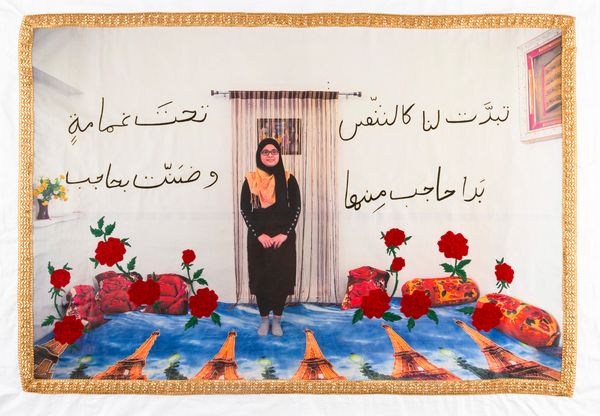

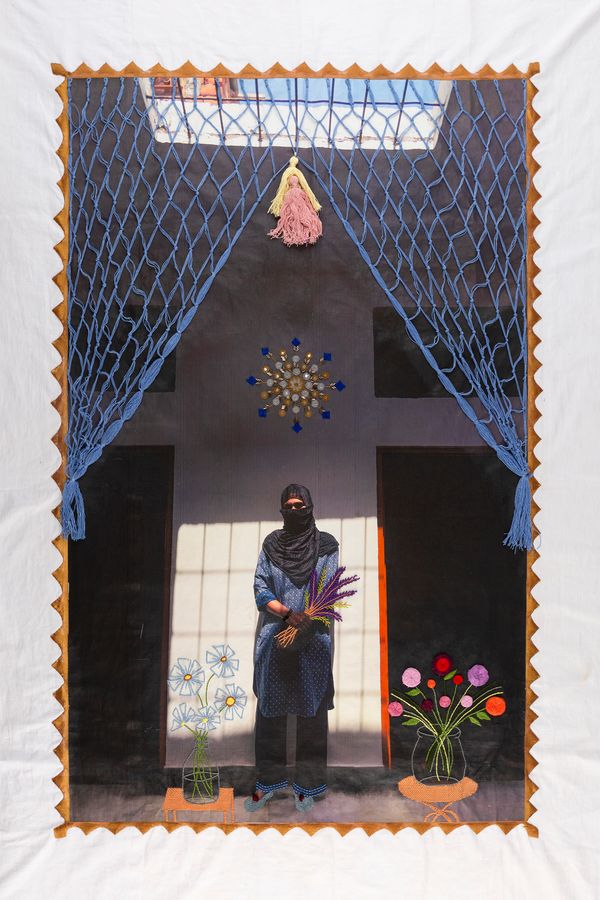

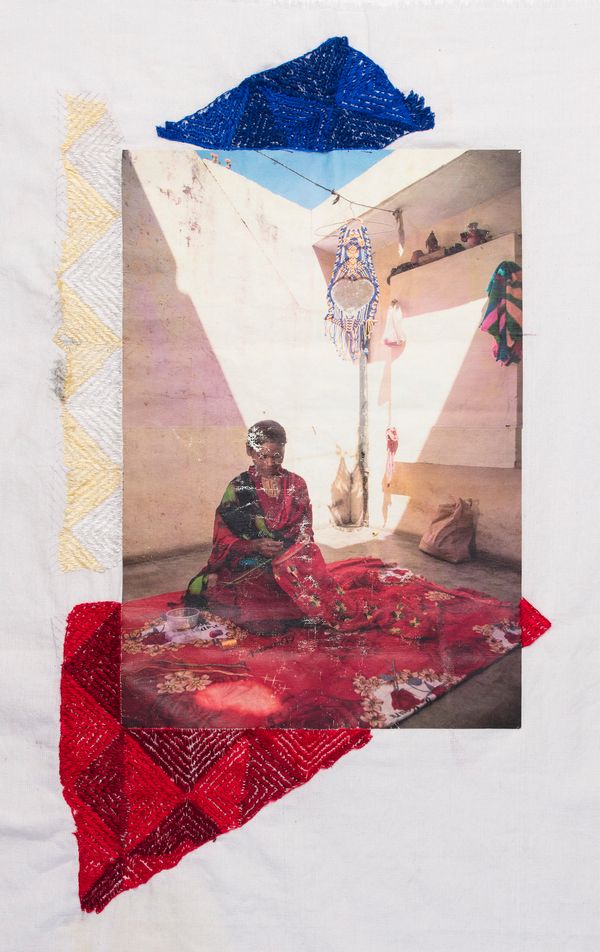

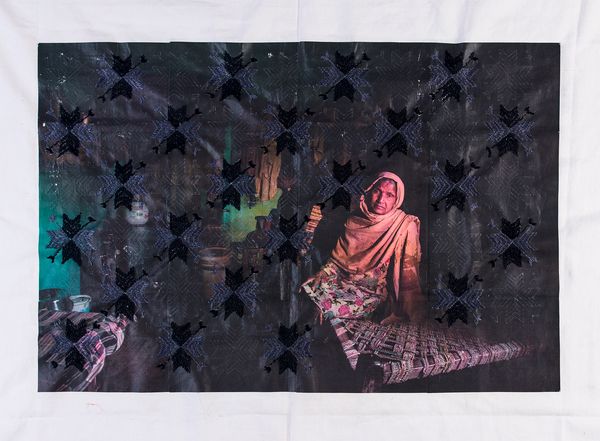

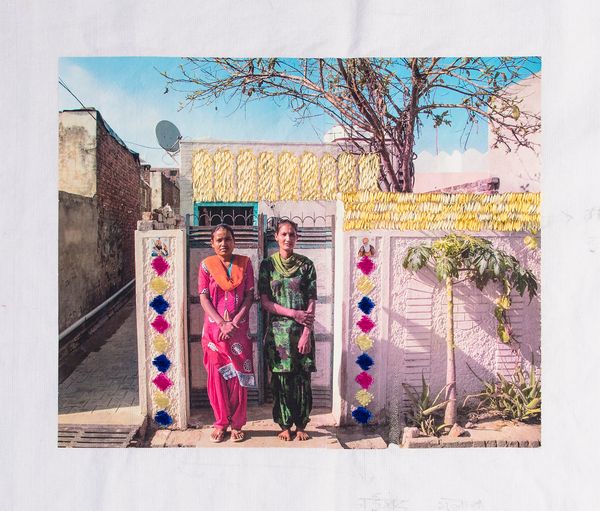

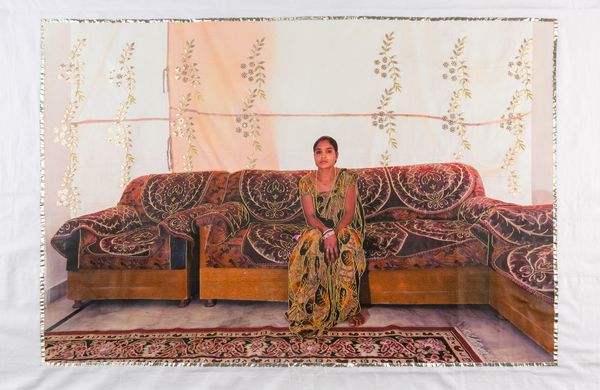

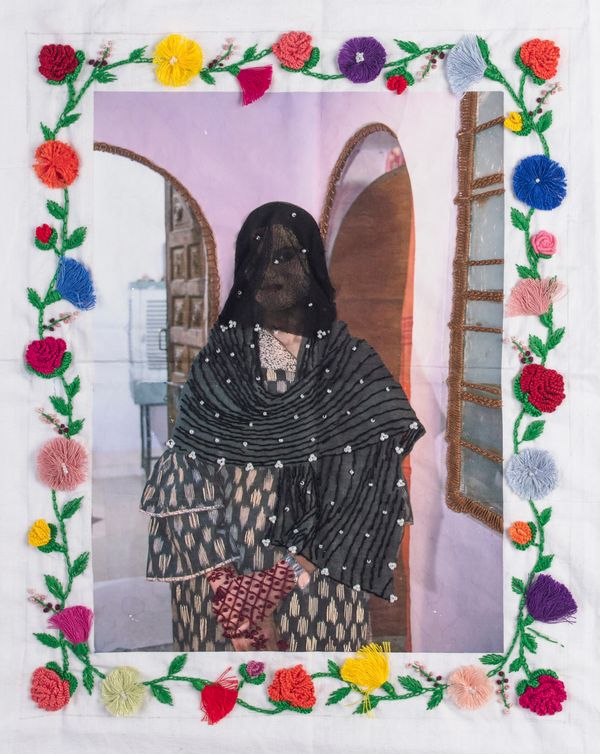

There has always been a sense of legacy being passed among women through this language of embroidery and handcraft, inherited by generations of women and passed along, to break the oppressor by simple but significant hand movements captured on fabric, written in thread.

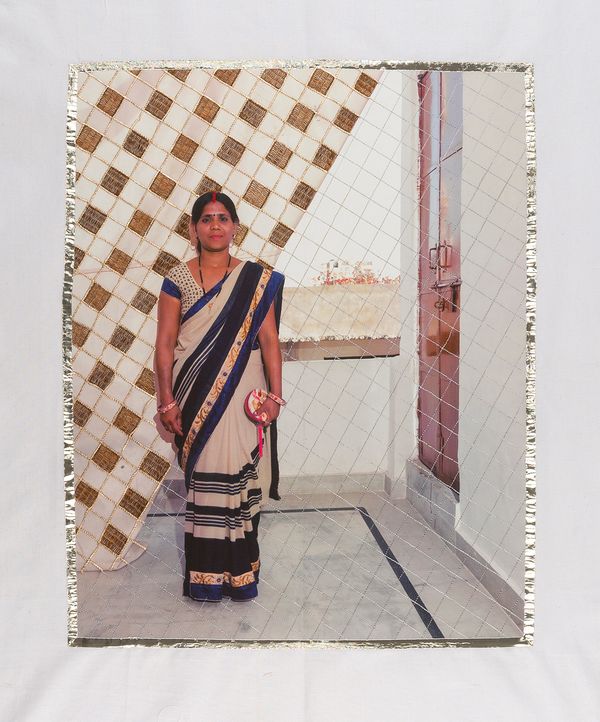

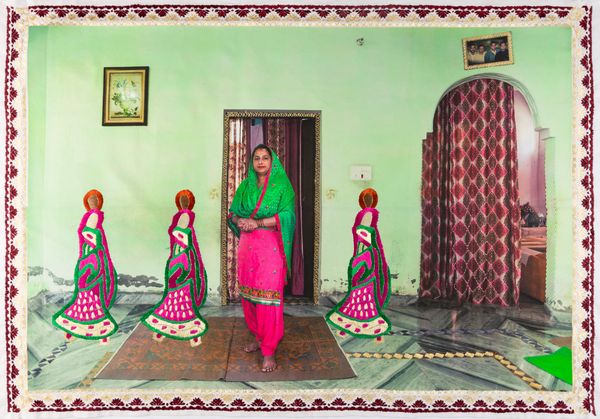

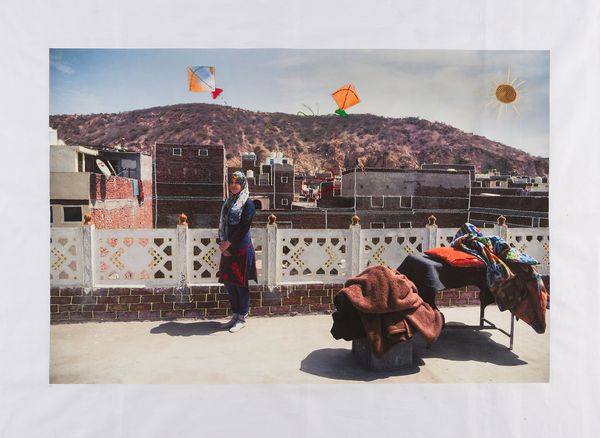

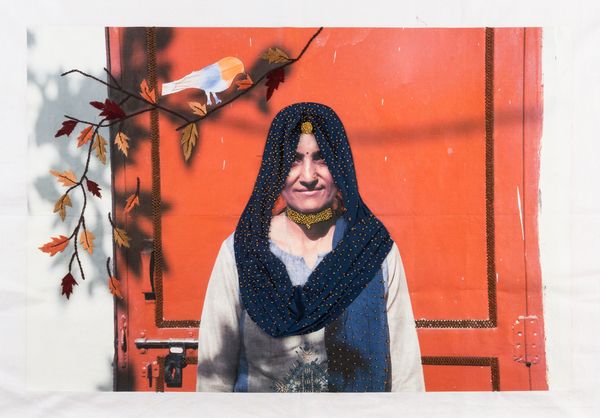

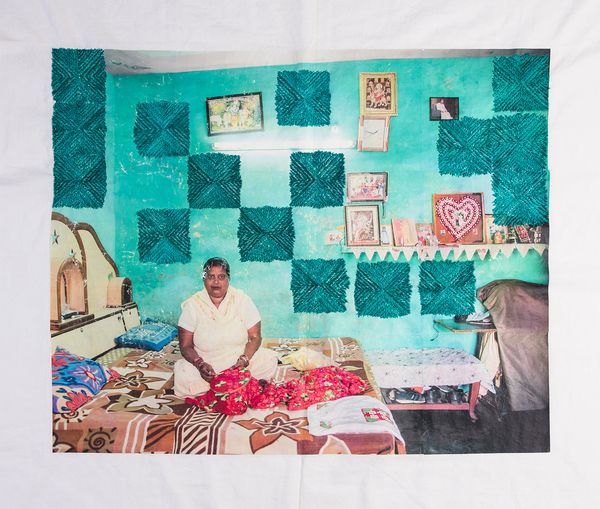

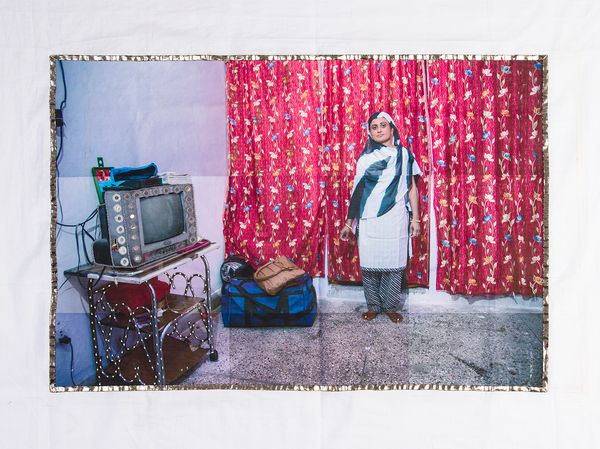

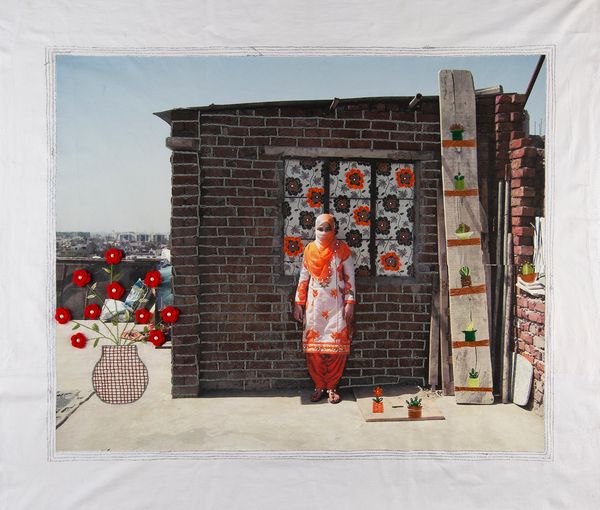

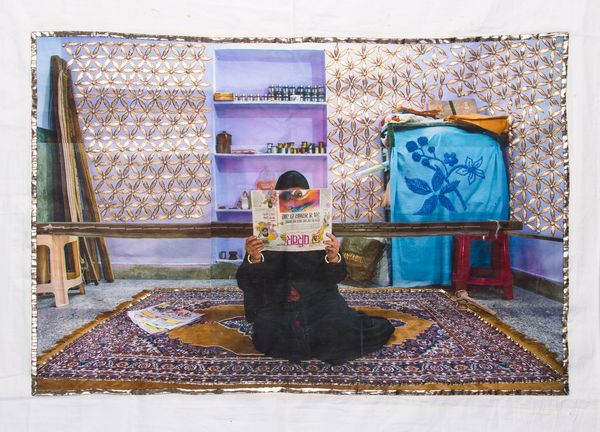

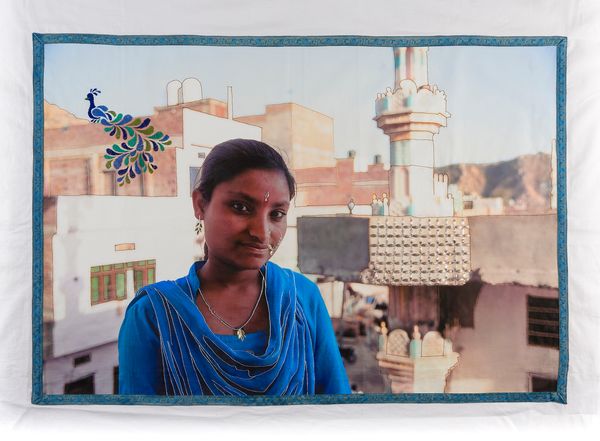

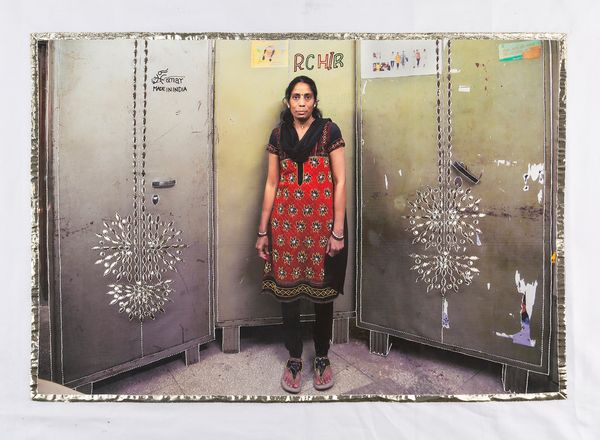

In Sanskrit, nā́rī means woman, wife, female, or an object regarded as feminine but can also mean sacrifice. While misogyny is hardly exclusive to one country or culture, India bears particularly ghastly symptoms of it. Women are in real danger there: the frequency of domestic violence in the country is impossible to ignore. While searching for women in India in self-help groups who are learning to embroider, I heard about women who weren’t allowed to come to the centres. They are either not allowed to leave the house, due to their husbands or fathers, or they felt unsafe leaving the house. I traveled to Lucknow, Jaipur, and Chamkaur Sahib where I photographed and interviewed these women about their harsh economic and social realities. Some women talk about their domestic violence. I had the privilege to be the bearer of the stories these women shared with me, to hear them, to question them, to understand the silences, the pauses, and to have the responsibility to retell, share, and pass on these stories.

I have grown up perceiving the photography of my country through a colonised eye. There was a conscious effort in stepping away from the aesthetic surrounding documentary photography of India, and photographing these women in the rooms they live or feel most comfortable in. I printed the portrait I took, onto the fabric of the region and asked them to embroider the portrait in a way that seemed fit to them, without any guidelines, giving them the agency to have authority over their own portrayal. These artistic collaborations subvert the idea of the artist as the main producer by giving each woman her own creative entity within her own craft. It also engages the problem of representation in portrait photography as addressed by giving women control over their own image.

It is a peculiar sense of belonging and safety found in the private spaces of the unfamiliar. There is an ease in unloading the pain in the agony of another; there is a strange trust and care in these private places, shared by women, known to women. These collaborations created a connection between me and the women in our shared language of art; by listening through our inherited language of embroidery, I learnt the true meaning of nā́rī .