Karukera - A love letter to Guadeloupe

-

Dates2022 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Guadeloupe, Guadeloupe

-

Recognition

The French Caribbean islands are dealing with a health crisis. A pesticide directly linked to cancer was sprayed on banana crops and today, 93 % of the adult population have traces of it in their blood. Looking around the island you would never know.

The submitted project is photographed by French Danish photographer Cécile Smetana and written by French Guadeloupéen writer Anaïs Makouke.

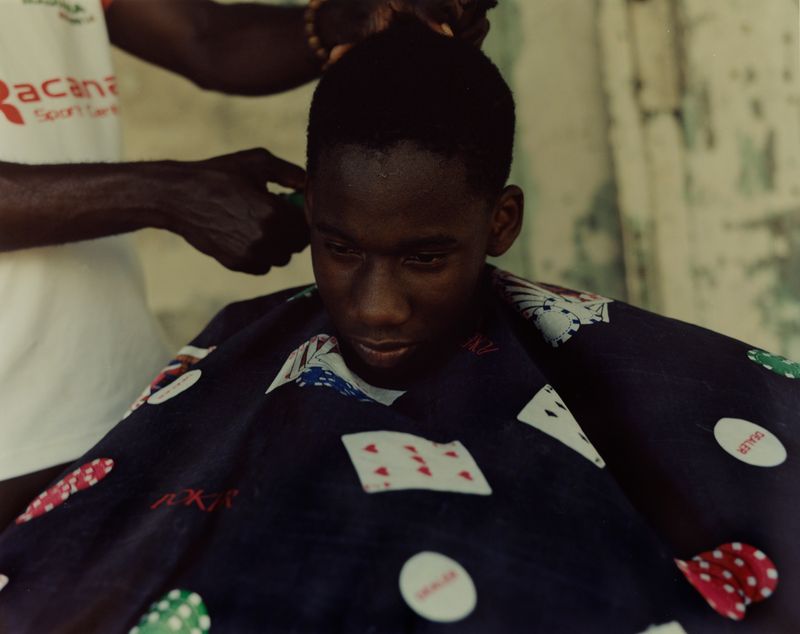

Guadeloupe’s colonial history began in 1493, when Christopher Columbus first arrived on the island. It was passed on from native Arawaks, who gave the island its original name Karukera meaning “The island of beautiful waters”.

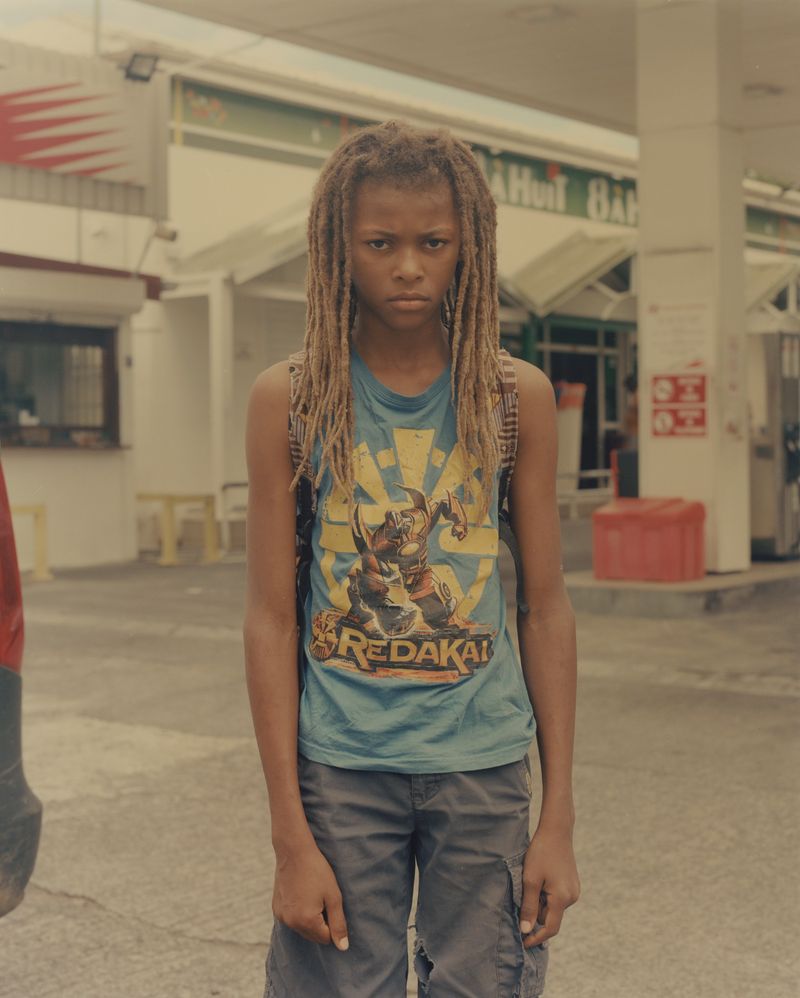

Today Guadeloupe is a French department, and the population is by definition French. People in Guadeloupe can vote in French elections and travel freely within the European Union.

Yet, the island's relationship to mainland France is fueled with distrust. Not only because of a complicated colonial history. But because, as the country struggles with a health crisis, France is nowhere to be seen.

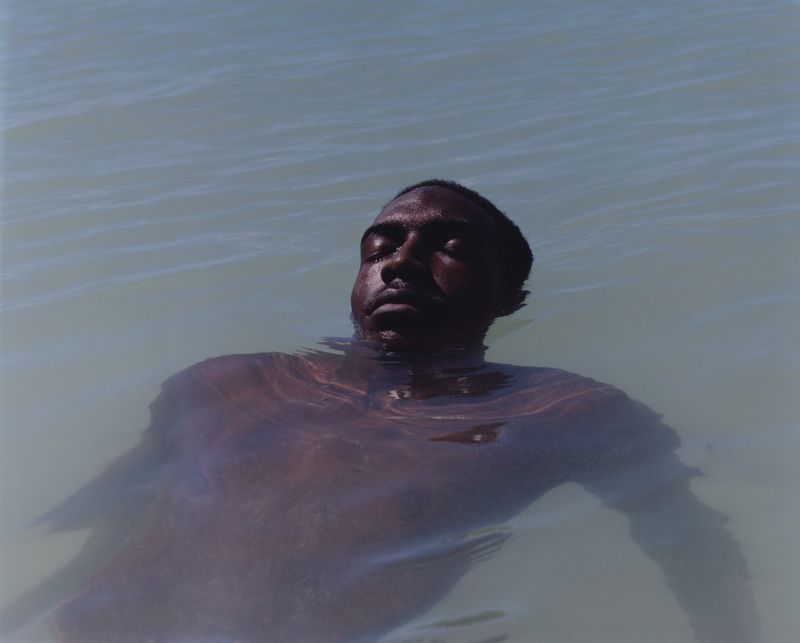

You can't see the poison, but you know it's here. In our rivers, our soil and in the milk of breastfeeding women. We live with it but didn't ask for it. Our government has benefited from our land and in doing so they have created an inescapable consequence that our bodies are paying for.

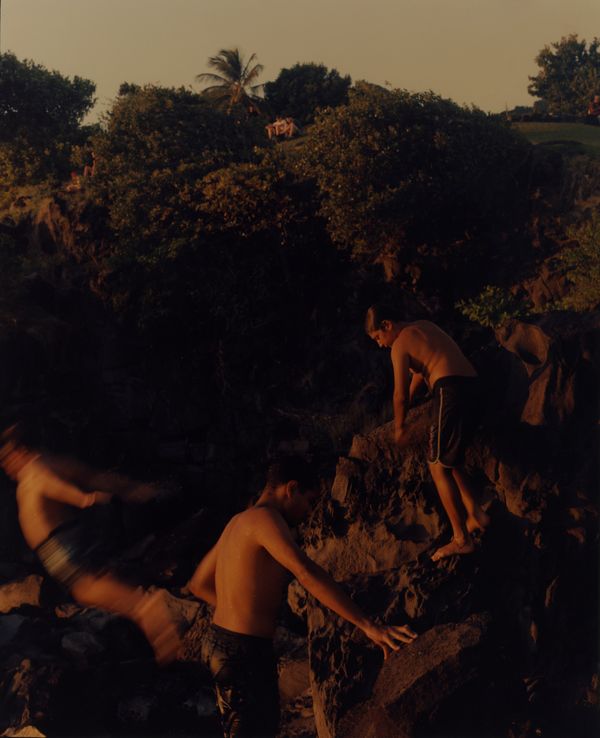

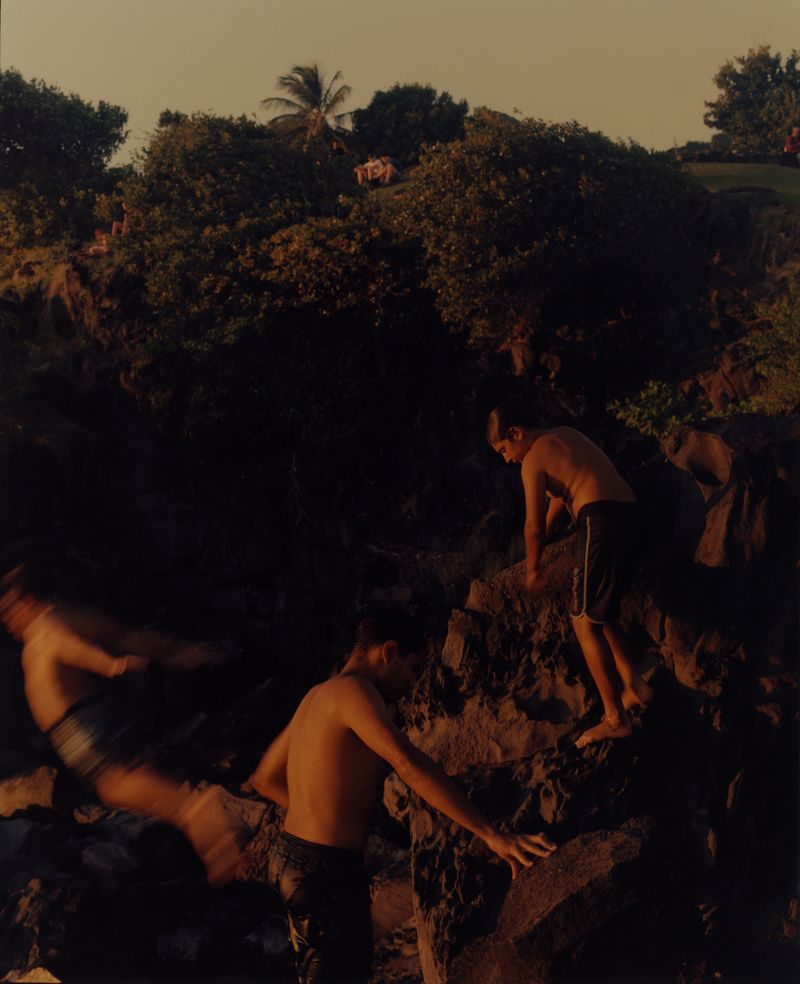

We don't avoid infected mountain rivers or coasts by the sea. This is our home and we cannot move. To me this is what it means to be Caribbean. We know how to endure, because there is in fact nowhere to run. The ground we walk on and the waters we swim in is what nourishes our bodies and our souls. Perhaps this is why our relationship with nature is so deep and perhaps this is why the pollution of our island is so hard to accept.

For two decades from 1972 to 1993 Chlordecone, a pesticide directly linked to cancer, was sprayed on banana crops on the island, and now more than 90 percent of the adult population have traces of it in their blood. Guadeloupe has one of the highest incidences of prostate cancer in the world and because Chlordecone is non biodegradable it is likely to persist in the soil for hundreds of years. Looking around at the island you would never know.

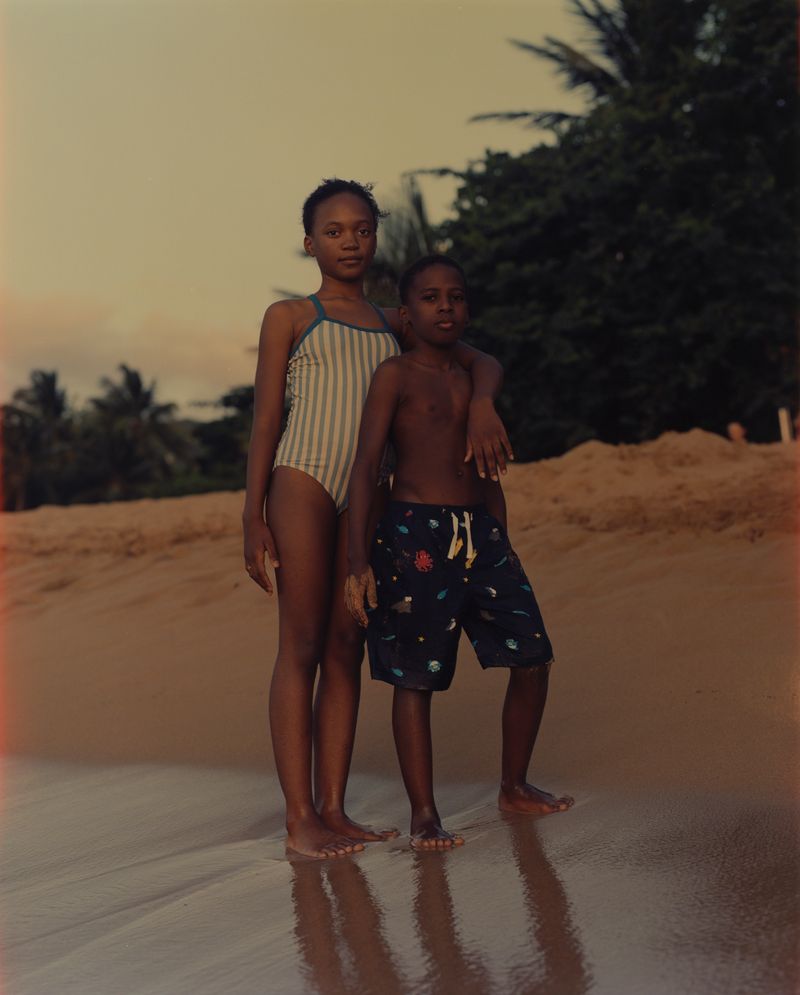

Long, sandy beaches glow in the dark and the light at sundown paints everything blue. Here in the middle of the southern Caribbean sea clouds hover dramatically over the ground, making the distance between earth and sky appear closer here than elsewhere.

There is this notion that islands are small, but in fact all Carribeans know that the discovery of an island is an infinite process. Forever subjected to natural events such as storms, cyclones, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions that transform and reshape our landscape. We are constantly at the mercy of nature.

From space you see the island shaped like a butterfly. I grew up on the right wing, in a small beach town by the name of Sainte Anne, known on one hand for its mountainous region and on the other hand for its beautiful clear blue waters. The beach was more than a beautiful postcard, to me it was the cradle of my childhood.

I remember spending my days after school picking low hanging gooseberry fruits and juicy, sticky mangoes from the trees on the savannah, as we called the field where my father tied his animals. We were left unwatched and the only rule was to never wear red as it could upset the grazing bulls.

Each summer my grandparents would round up their six grandchildren into the open top trunk of her beige Peugeot pickup truck, sticking us close together and telling us to hold on as our awkward tiny bodies bumped up and down as we drove down to the beach on rocky roads in the sunny afternoon light. We would spend the afternoon on the beach, laughing, fighting, screaming and jumping until sundown.

The nights are never silent here. They are loud, filled with sounds of cricket, frogs and spirits. if you're not from here, the noises will keep you awake, scaring the life right out of you. We would lay outside on the terrace, telling each other stories, each one more frightening than the last, about Caribbean flying spirits and creatures, who exist only in the dark, half human, half animal.

Each year, at the end of our holidays, my grandmother would wake us up in the middle of the night with a cup of special herbal tea, bitter and dry. She said it would clean our bodies and our minds and that it would prepare us for a new year.

She would then place a huge basin at the back of the house, fill it with water and huge piles of green leaves. We waited with excitement as the leaves turned heavy and wet and I remember entering the basin in pairs of two, laying down beside my cousin, laughing as our bodies scrubbed against each other in the bathtub.

Reality and magic have always been entwined in our reality on the island. I learned the history of my family, through the myths and traditions practised by my grandparents, but I learned the importance of nature from my father.

It's 5 in the morning and I am meeting my dad, Cesaire in the outskirts of the city, in a field where he is putting his cows out to graze. When I arrive it's already hot and I feel the sweat on my forehead as we are walking through the meadow. My dad seems to move without effort, running after the cows, dragging them each to their selected spots.

With his machete he cuts off coconuts from one of the palm trees and we sit down on the wet grass to drink.

“Working in nature is part of our family's history, of our identity”, my dad explains. I believe that work doesn't kill you, on the contrary, it keeps you alive. Your grandfather lived off the land, planting pineapples and sugar canes. It gave him a job, but more importantly it gave him purpose and he taught me the meaning of work.

I ask my father if he is worried about the pesticide pollution and he laughs nervously. “It makes me angry. I don't know anything about products and I refused to have my land analysed. It's been suggested, but I'm not interested. And if my land is polluted, what do I do? I'm not worried because I also know that I've used only a few products. I couldn't afford to buy any”.

I understand my dads point of view. The truth is knowing serves little purpose, because we can't do anything about it and and for most people in Guadeloupe, leaving is not an option.

I am part of a long and complicated European history, but it is the government's acceptance of allowing our bodies to be poisoned for years and years, that has awoken my sense of patriotism and my identity as a Caribbean woman.

I am French, a mix of Asian, African and European DNA. One identity does not rule out the other. I can be all of the above and the history of my island confirms this notion. That is the complexity of the Caribbean identity.