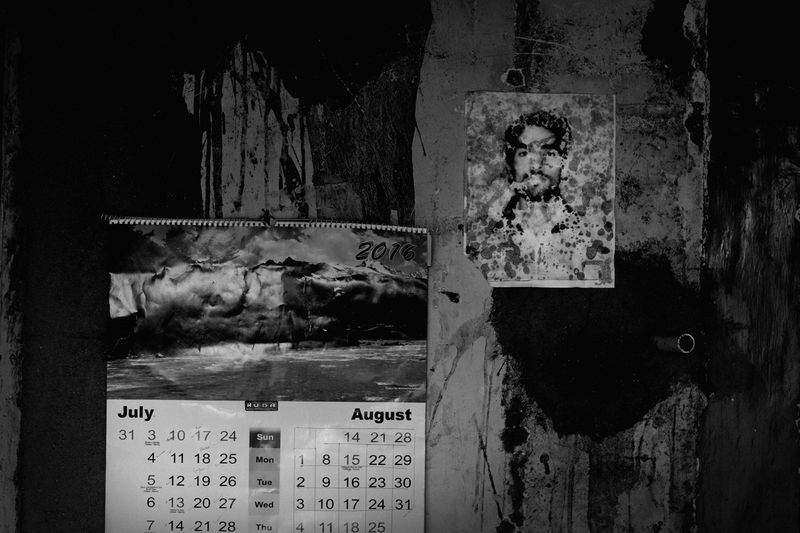

the endless wait

-

Dates2014 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Contemporary Issues, Documentary, War & Conflicts

The burden of enforced disappearances in Kashmir, which has been caught in a bloody conflict for nearly three decades, has been carried entirely by Kashmiri women – mothers and wives – whose loved ones were picked up only to vanish forever.

In November 2015, Hajra Begum, a 74-year-old widow, received a fist-sized bag wrapped in a thin plastic sheet. Inside it was the soil from the grave her only son who was subjected to enforced disappearance in the summer of 1997. Now her 18-year long wait was over.

Most women are not as ‘lucky’ as Hajra.

The phenomenon of enforced disappearances is a stark reality that Kashmir has been witnessing for the last twenty-six years. There are hundreds of cases where people have been taken into custody only to vanish forever.

Most of the times the burden is carried by women- mothers and wives of the disappeared persons who have spent their entire life and all their possessions, often in abject poverty, searching for their kin in jails, police stations, army camps and torture centers. In Kashmir, there is a term ‘Half-Widow,’ used for women who do not know whether their husbands are dead or

alive. These women remain in a state of confusion. There is a deep sense of loss but at the same time there is hope of being able to see their loved ones again.

Human Rights groups put the number of the disappeared persons somewhere between 6,000 and 8,000. The discovery of mass gravesites in recent years has brought more uncertainty to these women. According to a report published by the International People’s Tribunal on Human

Rights and Justice in 2009, there are 2,700 unmarked graves of unidentified people in North Kashmir close to the Line of Control that divides the Indian and Pakistani administered parts of Kashmir.