You'll know it when you feel it

-

Dates2012 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues, Documentary, Contemporary Issues

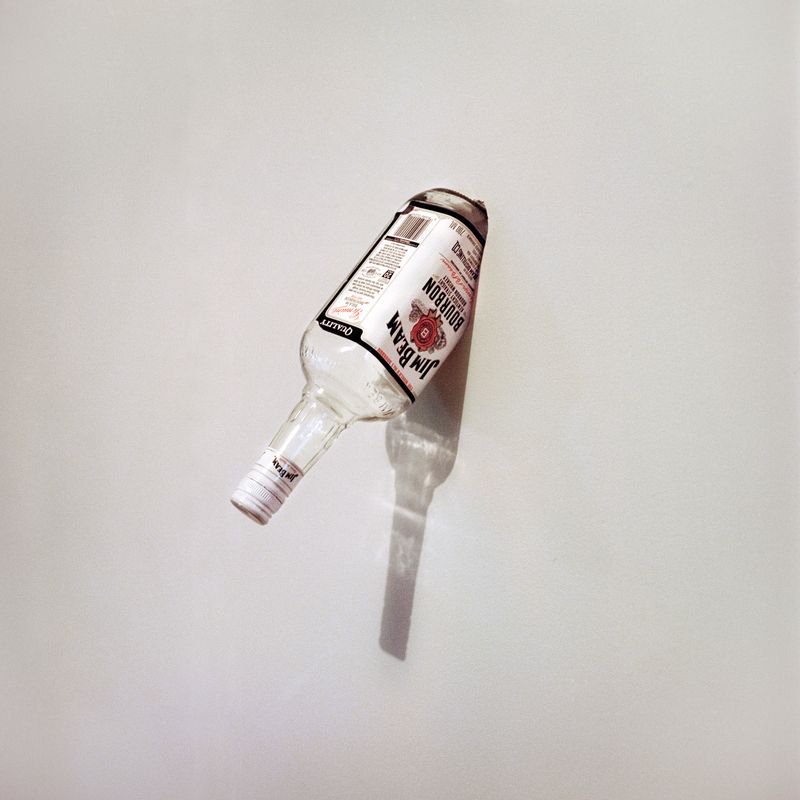

Weaving several narratives of love, longing and belonging, ‘You’ll Know It When You Feel It’ is a long-term project that accentuates the complex and cyclical nature of social disadvantage in Australia through the lived experience of several young women and their families.

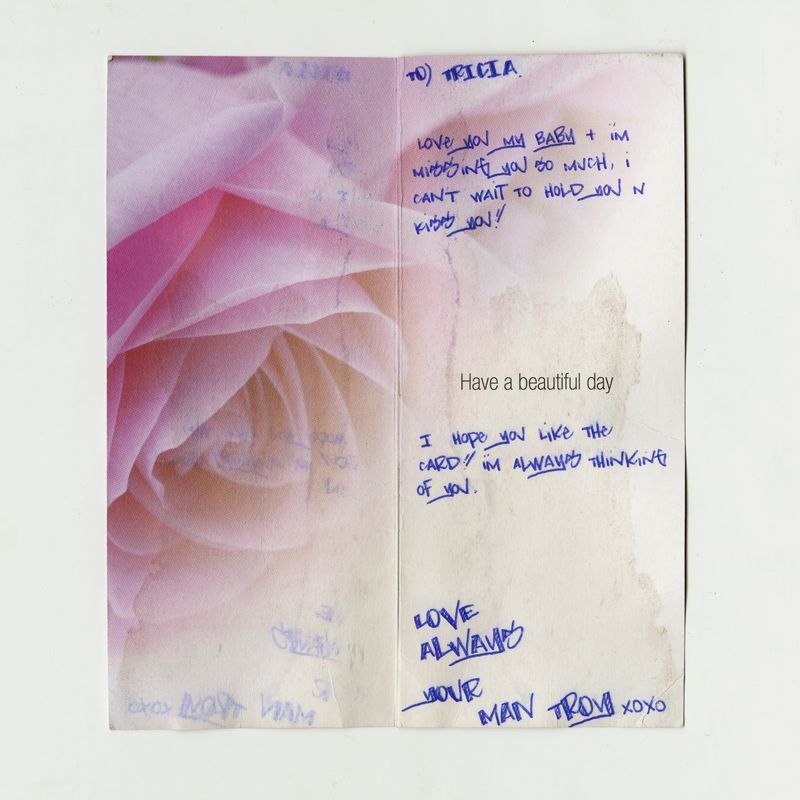

Rowrow smiled at me as she lay in a hospital bed, 38 weeks pregnant with her fourth child. Her prison greens sat carefully folder next to her, two corrective service officers hovered nearby. At 9:20pm we heard his first cries. I cut his cord and he lay content with his mummy. Yet it’s hard to celebrate a birth when you know what’s coming.

Four days later, with tears in her eyes and breasts full of milk, Rowrow was handcuffed and transported back to prison. The next morning baby John and I travelled 8 hours by train so he could be with family. Seven weeks later, in a gesture of cruelty only bureaucracy could invent, Rowrow was released early on bail - the damage already done.

I never imagined my girlfriends would be incarcerated. Growing up, it was usually our boyfriends. It’s easy to grasp now when I consider, women, specifically First Nations women, account for the most significant growth in Australia’s prison system. I grew up in a small town in Australia notorious for its open drug culture and alternative lifestyles. As young women, our choices were limited; violent relationships and becoming a mother at a young age were normal, and the dream to ‘leave and start a new life’ meant leaving our family, friends and community behind.

Yet, rather than understanding the complexities of trans-generational trauma caused by colonisation and on-going dispossession, or the cyclical nature of social disadvantage in Australia, women continue to be blamed for being homeless, beaten, pregnant, unemployed, addicted to drugs or incarcerated.

As such, I have spent a decade documenting women in my life; my twin, my step-sister, and new and old friends, as they grapple with the complexities of motherhood, trans-generational trauma, turbulent relationships, bureaucratic violence, and the burden of low expectations. Each experience has been rewarding, complex, & at times heart breaking.

By acknowledging the resilience of participants & valuing the process of intimate, long-form storytelling, I hope to create a platform for each young woman’s circumstances, choices, achievements & struggles to be heard & understood. Weaving several narratives of love, longing and belonging, ‘You’ll Know It When You Feel It’ is a long-term project which aims to accentuate these invisible stories in Australia—a country where racism and class bias thrives and where those experiencing the complexities of poverty are misunderstood, demonised and dehumanised.