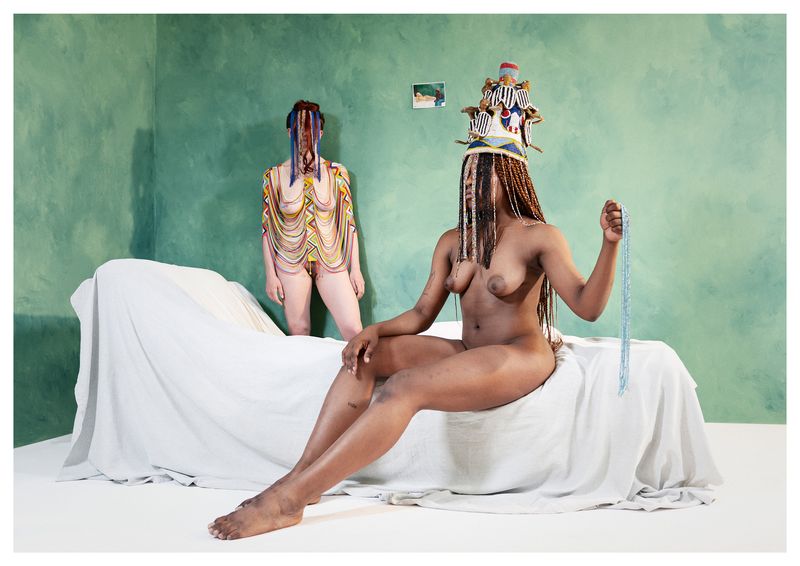

USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS - La Blanche et la Noire

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Tervuren, Spain, Cairo, Nigeria, Ghana

The project explores ownership and colonialism, addressing spoliation, race, and gender. It questions the universal nature of museums and examines the representation of black women in Western art.

In Roman law, ownership was defined as the absolute full enjoyment over an object or corporeal entity. The USUS was the right that the holder had to make use of the object according to its destination or nature, FRUCTUS was the right to receive the fruits, ABUSUS was the right of disposition based on the power to modify, sell or destroy the object or given entity. Property was perpetual, absolute and exclusive.

Questions of spoliation, hegemonic narratives, race and gender are addressed based on the concept of ownership.

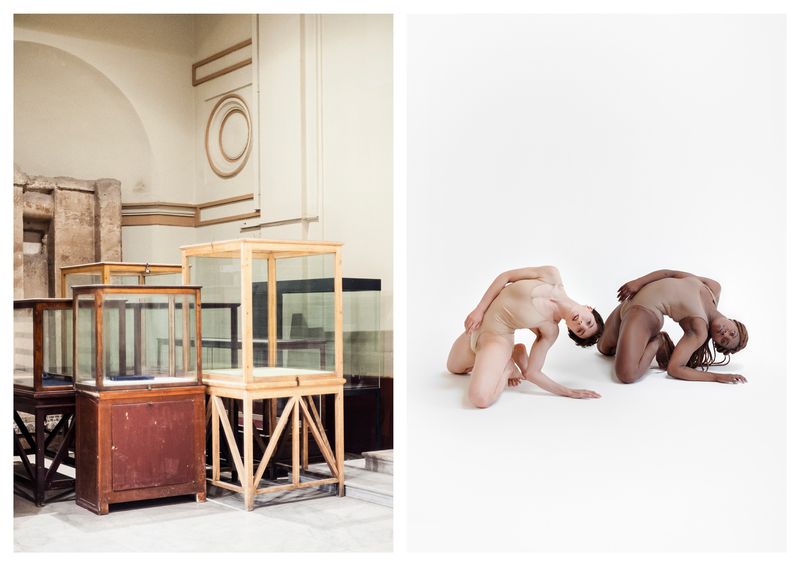

Museums originated as institutions more than 300 years ago, when certain royal collections were made accessible to the great public. They would hence become instrumental tools in the construction of identity and the definition of Nation. And bearing in mind the outstanding colonialist origin of many of their collections, then conflict with History narrative, the creation of knowledge and, consequently, collective and individual memory, becomesunavoidable.

A revision of the relationship between anthropology and museum collections assembled from a despoiling colonial past, its historicity and historiography, justified by a quest for discovery – almost always legitimated through a “rescuing” spirit –, leads to the conclusion that for decades these spaces have reinforced exotism and distinction, intrinsically related to supremacist discourses.

Museums as creators of imaginaries, as institutions that aren’t and have never been neutral holders, yet have benefited from exhibited objects and artefacts. They are a powerful tool for instilling respect, changing prejudices and revising History. Or dangerously the opposite.

Is the concept of museum universal?

Let’s look behind the curtain.

Untie to tie.

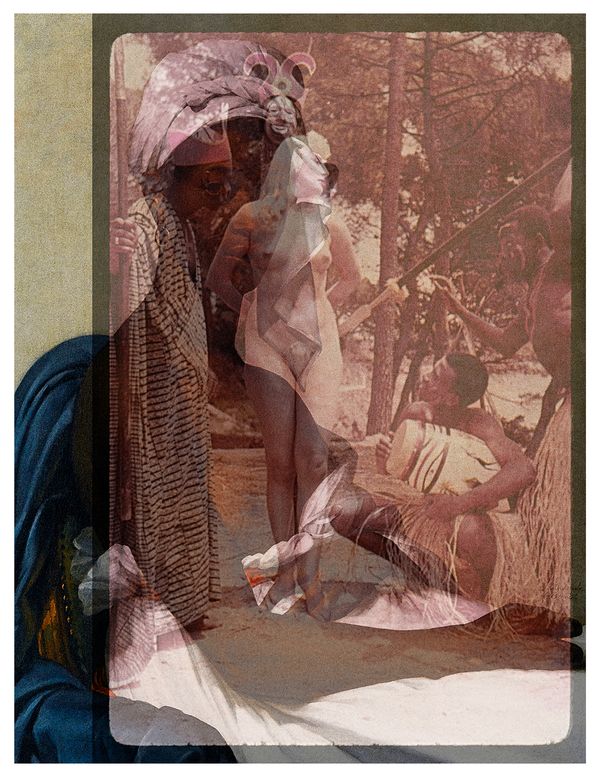

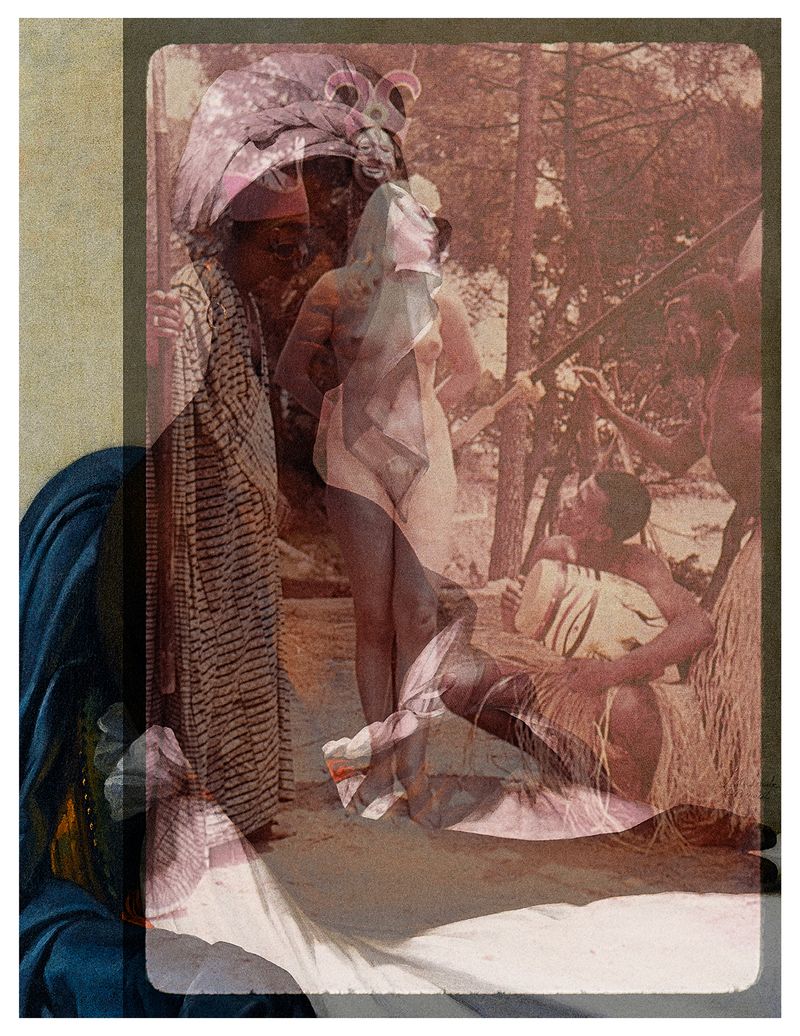

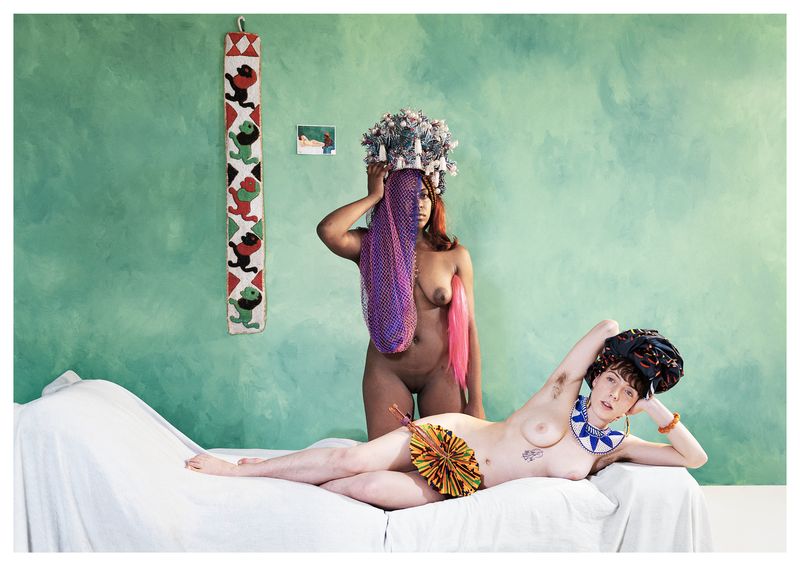

Intrinsically related to ‘otherness’ and linked to the colonisation of the concept of woman, it is pertinent to point out the responsibility of the risky representation of the black woman in the history of Western art. Stereotypes of black sexuality: bold, available and subservient; and also the gaze/position between white women and black women, the relationship of the black woman’s body and identity with the settler that leads to perpetuate stereotypes, reinforce exoticization, allow cultural appropriation, mark out hierarchical differences, etc.…

Eternal Odalisques. Originally, they were female slaves who served in large households -in Muslim community, they were ‘simply’ hard working servants owned by powerful and wealthy households-, but wrongly understood due to the Orientalist school of painting, in which odalisques and other female slaves were often subjects of painterly interest, reinforcing once again a demeaning imaginary. In ´Orientalism´ (1978) Edward Said puts forward a critical concept that describes the way in which the West elaborates a reductionist representation of the Orient, closely linked to the imperialist societies, therefore being an inherently political and power-serving term. As with the Orient, the gaze towards the Other is constructed from the West by a complex process of internalisation of a romanticised version of local culture, explicitly created by the settler powers of the time and all their paraphernalia accompanying it; as, for example, the colonial literature of Joseph Conrad.

Since then, demands have been made for the development of literary theory and cultural criticism, especially in relation to the methodology used by scholars to examine, describe, or explain the ´Other´, generating a large universe such as that of post-colonial studies. One might also consider directing discussions around the book as a cultural critique.

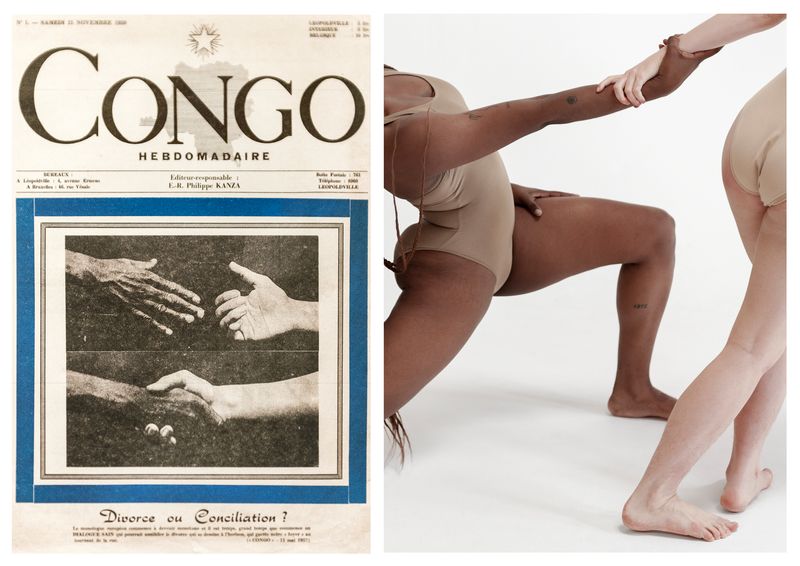

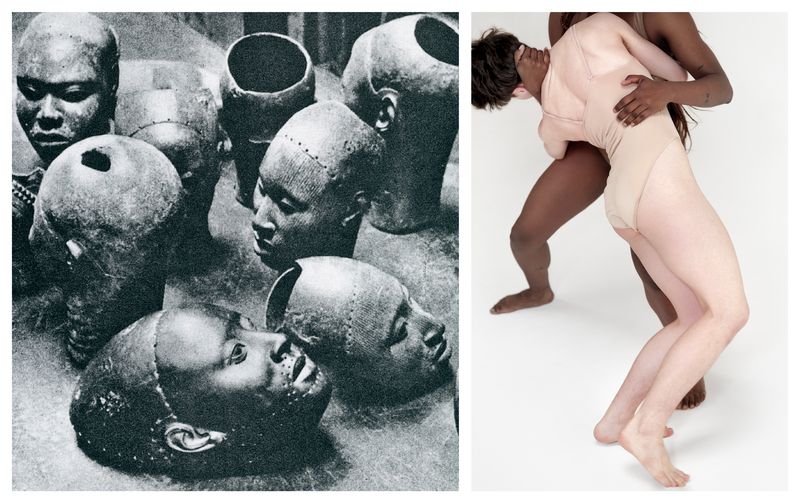

[Is the reproduction of archive images responsible of a reinforcement of a stereotypising gaze?]

The odalisque leads to a larger discussion of race within art and art spaces.

How does the colonial endeavour play out across the female body, aesthetically hiding the violence just beneath the surface?

The black female body has long been a distinctive site of transgression and deference to outsiders, especially Europeans. Often reduced to a mere sum of its parts, the extensive records of its oppression are characteristically rooted in a history of slavery, colonial conquest and ethnographic display, creating a collective imaginary based on an overwhelming colonial archive. The mistreatment of the black female body/identity cannot be located in one time period or one offender, but has a particularly long history of scrutiny under Western imaginary as early as the 16th century. In the European context, the black female has been associated with many destructive stereotypes, labelling her as sexually deviant, primitive, subhuman, hyper-sexual, an uncontrollably erotic creature … all under the white gaze. Over time, this same body has been stripped of its autonomy, purged from intellectual spaces and exposed raw as a "bizarre" public spectacle.

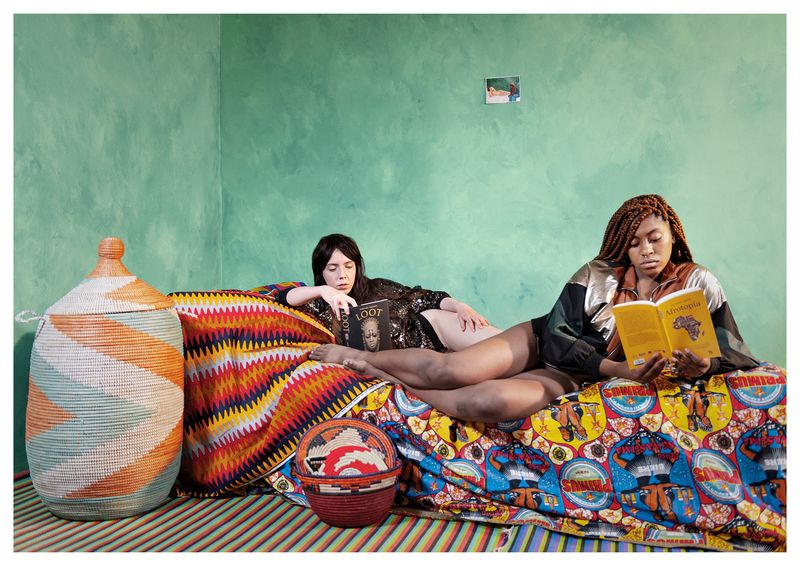

And as a starting point my enthralment with the painting La Blanche et la Noire by the French-Swiss painter Félix Vallotton (1913, Hahnloser Foundation Collection, Winterthur, Switzerland). Inspired by Manet’s Olympia and Ingres’ Odalisque à l’esclave, it depicts the Sapphic love between a sylph and a black woman. Unlike his predecessors, Vallotton dispenses all exotic references.

The familiar reclining nubile female nude of Art History, frozen in time and laid out for voyeuristic pleasure in a post-coital doze, cheeks ruddied from exertion. We assume the gaze, not of the white bourgeois Western male, but a ‘minority ethnic’ woman who is seen to be consuming all the visual pleasures that privileged male archetype feels entitled to. For embedded in this dyad before us is an Orientalist fear and desire for interracial erotic fantasy. Thus, while the western eye bristles at being cast as the black ex- slave, this is tempered by the suggestion of illicit and transgressive relations between the two women.

[But, is my vision being Eurocentric? am I falling into an exercise of victimisation? how to establish a horizontal dialogue? is it essential to collect objects, to exhibit the body? Is restitution a healthy act? Could it have the opposite effect by reinforcing the dependent link with the narrative constructed from power and privilege?]

Starting with a recreation as faithful to the original as possible, then going through different scenarios, it leads to a contemporary reflection in which both women appear reading books as Afrotopia by Felwine Sarr (co-creator with Benedict Savoy of the report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron on the issue of looted objects in French museums, notably the Quai Branly Museum in Paris) or Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes by Barnaby Phillips.

A two-voice dialogue around gender, race and colonialism emerges between them.

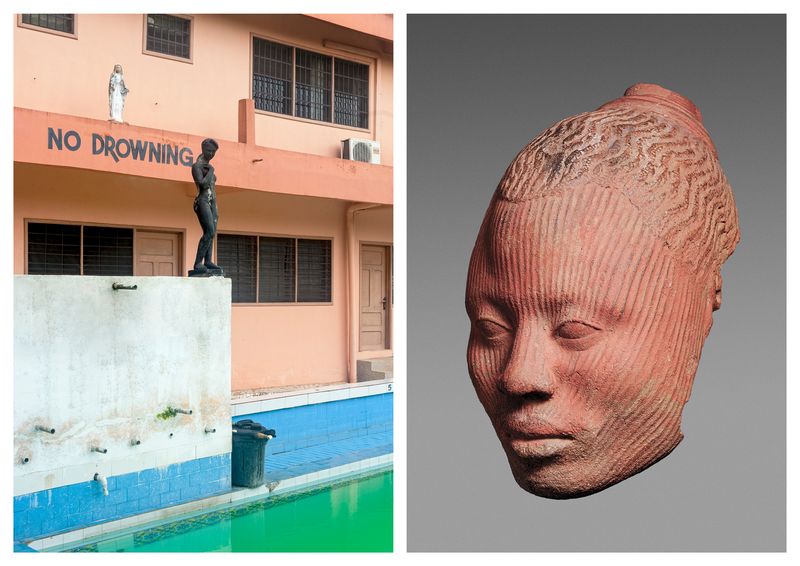

Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone? Ownership, restitution, reparation, recontextualization... who has agency to give, return, loan, adjudicate, rename?

In order to maintain their economies and symbolic dominance, Western governments expressed fear, wondering whether, in the event of return, African artefacts would be properly maintained and what would be left of their own collections. Many of these museums have appointed themselves as universal guardians of hundreds of thousands of objects which overflow their basements, justifying the greed involved in this with a pathetic paternalistic attitude. This kind of egoistic and supremacist arguments were questioned within the Sarr and Savoy Report, which urged for transparency when it comes to determining the origin of the artifact - whether it was stolen, acquired, or bought during the colonial era - as well as for balance between both continent’s possessions in regards to enhancing their political and cultural relations.

Up to 90 percent of the cultural heritage of sub- Saharan Africa is held outside the continent.

The restitution should/could not be just a legal act of returning the stolen artifacts, but an act of reconciliation and recuperation of the previous damage done. The legitimate owners should be entitled to use those objects to reclaim their histories, their voices, and re-integrate them into their communities, and cultures to build a stabile new cultural policy and both internal and external relationships. Or perhaps assess the possibility that certain artefacts may not be possible to return for various reasons. Dialogue, questioning and listening are priorities.

[But, am I being too condescending in considering that restitution "gives them back" something they logically already have (voice, History)? Is this, once again, a Eurocentric mindset? To think that the history of the African continent is only its relationship with ´us´?]

Let's provoke a polyphonic debate on the function of objects and their role in processes of subjectivation of the individual, as well as in building collective identities. One central concern is the epistemology of the object, which has been created by a distanced Western view on it, as that by anthropologists, art historians or museum curators. These objects are mutants! They have been moved to the Western world and now they have another history; they are incarnating something else. Even if one could elaborate a kind of fantasy of magical power, or "inbetweenness" between the world of the visible and the world of the invisible, trying to come closer to understanding the role they were supposed to play in their original societies, incarnated as divinities, it may be a speculative concept from a position of privilege.

Maybe It’s not about restitution. It’s the debate on restitution. Are these objects watching us and listening to us? They need to be part of this conversation. These objects have to help bring us together around the conversation and make this conversation evolve with the evolution of the whole human society, without distinctions of cultures, genders, social classes, fields of work, etc. Because the “restitution” subject is much more complex than only a North/South legacy, between Africa and the West.