The Rift.

-

Dates2018 - Ongoing

-

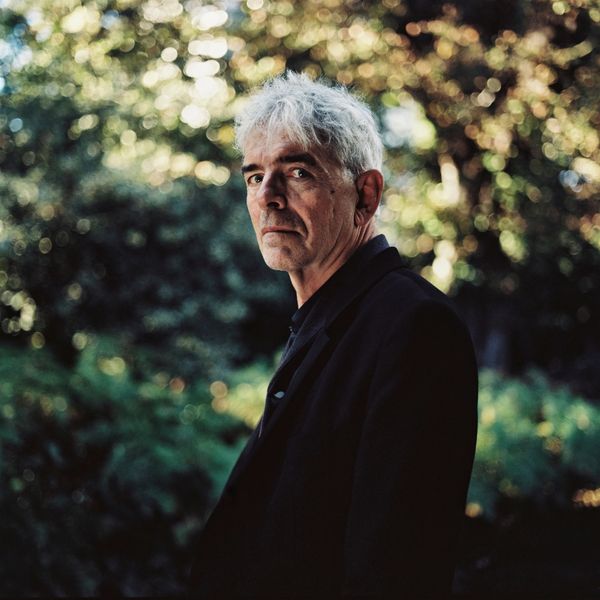

Author

- Location United Kingdom, United Kingdom

The Rift - Fracking in the UK

Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’ as it is more commonly known, involves pumping a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high-pressure deep underground to break apart rock, and extract natural gas and oil. Some support the practice, viewing it as an opportunity for job creation, energy security, and even a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future. Others are deeply concerned.

This first chapter of this ongoing project on fracking in the UK is set at Preston New Road, a site midway between Preston and Blackpool, two towns in the North West of England. Preston New Road is the epicenter of the UK's fracking resistance, and where fracking first occurred in October 2018, midway through this project.

Though fracking has really just begun in the UK, the process has provoked nationwide debate for almost a decade. The issue initially entered into public consciousness when Cuadrilla hydraulically fractured the UK’s first shale gas exploration well at Preese Hall in 2011. Two earthquakes were detected and a moratorium on the process enforced. This was only lifted in late 2012 after the introduction of a new regulatory regime geared toward monitoring and reducing seismic risk. Since fracking began more than 60 tremors have been detected, several significant enough to halt operations.

Many of the locals feel that their democratic rights have been infringed – with the local (Lancashire) county council rejecting plans for fracking to go ahead, only for central government to overturn their decision. This served to further reinforce much of the ideology that underpinned the area's dominant Brexit vote – that London was its own entity and the wishes of the rest of the country were being forgotten.

At Preston New Road, locals join forces with climate campaigners to protest against the process on environmental, social and political grounds. Opponents stress the potential environmental and health impacts: earthquakes; water wastage; air and water pollution leading to cancers, birth defects and damaged reproductive health. Other concerns include its detrimental effect on house prices, noise pollution and the industrialisation of the countryside. Ultimately, it represents a continued investment in fossil fuels at a time when eliminating our reliance on them is crucial.

This project focuses on the community that has grown up around the fracking resistance, and particularly the environmental protectors who reside at the two permanent protest camps at PNR - Maple Farm, and New Hope Resistance Camp. The aim is to give a human face to the numbers of arrests quoted in local and national papers, to push the individual stories front and centre. Why do people care so passionately about a practice that is largely invisible?

Many of the protectors I met were doing this for the future of their children, and in fact, involved their children in their activism. Many were first time protestors, and many, until now, had always trusted the police. This story of resistance comes at a pertinent time in the UK, with activism and mistrust of the government's authority at an all time high.

To redirect the narrative away from the traditional image of protests, I wanted to get to the heart of the issue, and lived in a tent alongside protectors at Maple Farm for several months. My aim also, to make visual the as-yet invisible environmental issues that many fear fracking will inflict. These I depicted by processing selected film images with a constituent chemical of fracking fluid. In the UK, operators must declare what chemicals they use. Cuadrilla fractures shale rock by pumping a mixture of water, sand, and a chemical called polyacrylamide through a horizontal well. Although the Environment Agency has assessed polyacrylamide as being non-hazardous to groundwater, it is a controversial ingredient given its ability to degrade and secrete acrylamide: a known toxin and carcinogen.

I combined this with water from Carr Bridge Brook, the nearest watercourse to the site. In 2017 the Environment Agency recorded two separate incidents of water, which contained silt, leaking into the brook from Preston New Road. Both instances breached Cuadrilla’s permit conditions and a discolouration of the water was observed. Many fear that contaminated water could runoff from the site and pollute the surrounding area.

Film chemistry relies on clean water to be able to be processed properly. By employing a disrupted aesthetic, I allude to the potential threats of the practice on the landscapes and lives of those pictured. I wanted to create something beautiful from something damaging. In some ways, this duplicity creates more discussion, and will hopefully raise awareness of the process involved in fracking.

The well at Preston New Road is only the start. It is not a commercial site: the gas will be flared not captured. An estimated 20 to 40 wells will be needed to ascertain the commercial viability of the process. But, if the industry does take off, the UK’s countryside will be covered. There are already plans for further exploration at nearby Roseacre Wood, across North West England, Yorkshire and the East Midlands. This summer, the UK Government set up a consultation on whether shale gas development should become ‘permitted development’: a category usually reserved for activities like putting up a garden shed. This would enable fracking companies to drill at will without applying for planning permission.

Fracking is more common in the US where it has revolutionised the energy landscape: over 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the country since 2005. Despite Europe being projected as the new ‘fracking mecca’, it has been largely unsuccessful: the process is not permitted in France, Germany or Bulgaria; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all placed their own suspensions on it. In the UK, estimates suggest that the amount of shale gas lies between 2.8 and 39.9 trillion cubic metres. According to former Prime Minister David Cameron, if only 10 percent of those reserves were extracted, this would provide the equivalent of the country’s total gas needs for 51 years.

In May 2018, the UK Government introduced a number of measures to help facilitate the practice, including a £1.6m fund for planning authorities to speed up fracking applications.

What is happening at Preston New Road may seem insignificant but it is an indication of our continued reliance on fossil fuels on a global scale and the myriad environmental issues these cause. Midway through this project, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report pointing to the importance of limiting global warming to a maximum of 1.5C, stating that we have only a dozen years left to do so. Carbon pollution would have to come down to zero by 2050 for us to achieve this.