The Price of Bushmeat

-

Dates2016 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Editorial, Documentary

Wildlife – including endangered species – flowed through a bushmeat market in Kumasi, Ghana, despite a hunting ban. The scale and conservation implications of the trade are under-documented and under-reported, but one estimate posits that Ghana's wildlife biomass has declined by 75% since the 1970s.

This project began accidentally. I was assigned to shoot a story about the potential risks of zoonotic disease transmission arising from the bushmeat trade. However, while those risks were readily apparent, it was the conservation dimensions of the business that struck me most forcefully.

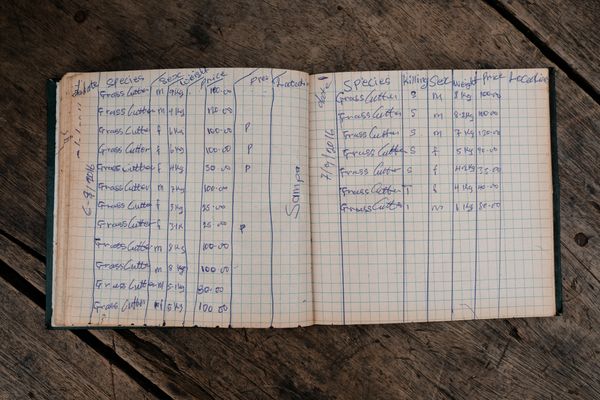

A hunting ban was in force at the time, and grass cutters (greater cane rats) were the only legal quarry, yet animals of all descriptions flowed through the market with the obvious collusion of the officer responsible for enforcing the ban.

Bushmeat is a complex issue, and its nuances vary around the continent. For some people in West Africa, game meat is a delicacy or a healthy and natural diet option, worth the premium prices it commands in urban centres. In rural areas, it may be a necessary alternative protein source, and correlations have been shown between the price and availability of fish and the extent of hunting. Demand from the diaspora is known to fuel an illicit international trade, and while this is significant, its exact scope and extent remain unclear. There are international cultural factors that influence perceptions (for example, why is it “venison” in a London restaurant, but “bushmeat” when we refer to Africa?), as well as superstitions that surround some animals and their body parts. And then, of course, there are the pressures of population growth and habitat loss, and the spectre of corruption.

There is a dearth of current empirical data on the bushmeat trade in West Africa, and the issue and its implications remain under-documented and under-reported. It is clear, however, that wildlife populations are declining precipitously. One estimate, now dated, posits that Ghana’s wildlife biomass has declined by three-quarters since the 1970s.

The images I have shot to date were taken over a few days, on a trip constrained in both scope and time. I seek to return to the region to shoot in-depth, and to follow the story’s threads from the more accessible urban centres back out to its wilder roots. I have begun the process of seeking partners and collaborators, and ultimately hope to contribute to raising awareness of the trade and its implications, and to furthering discussion of the ongoing sustainability of both the trade and the wildlife on which it depends. If we are indeed in the Anthropocene, our acceptance of this cannot be passive.