The Platinum belt

-

Dates2016 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Contemporary Issues, Documentary

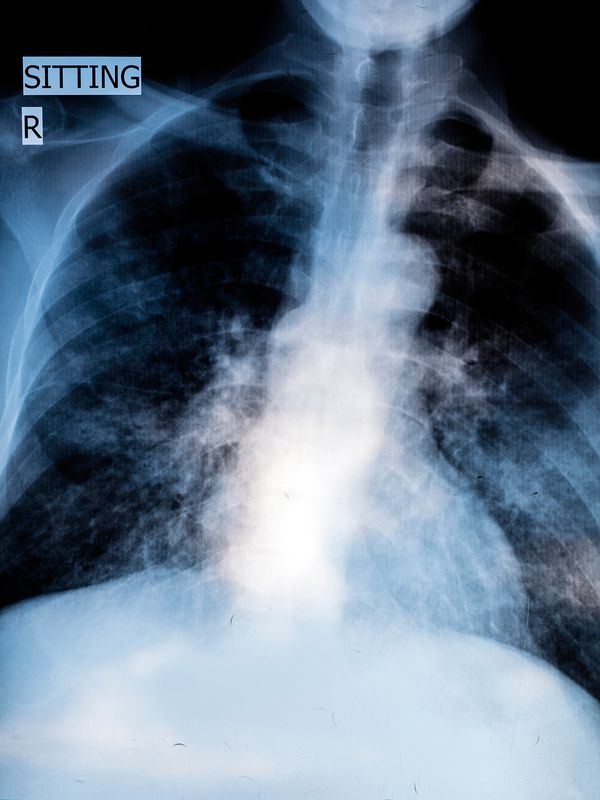

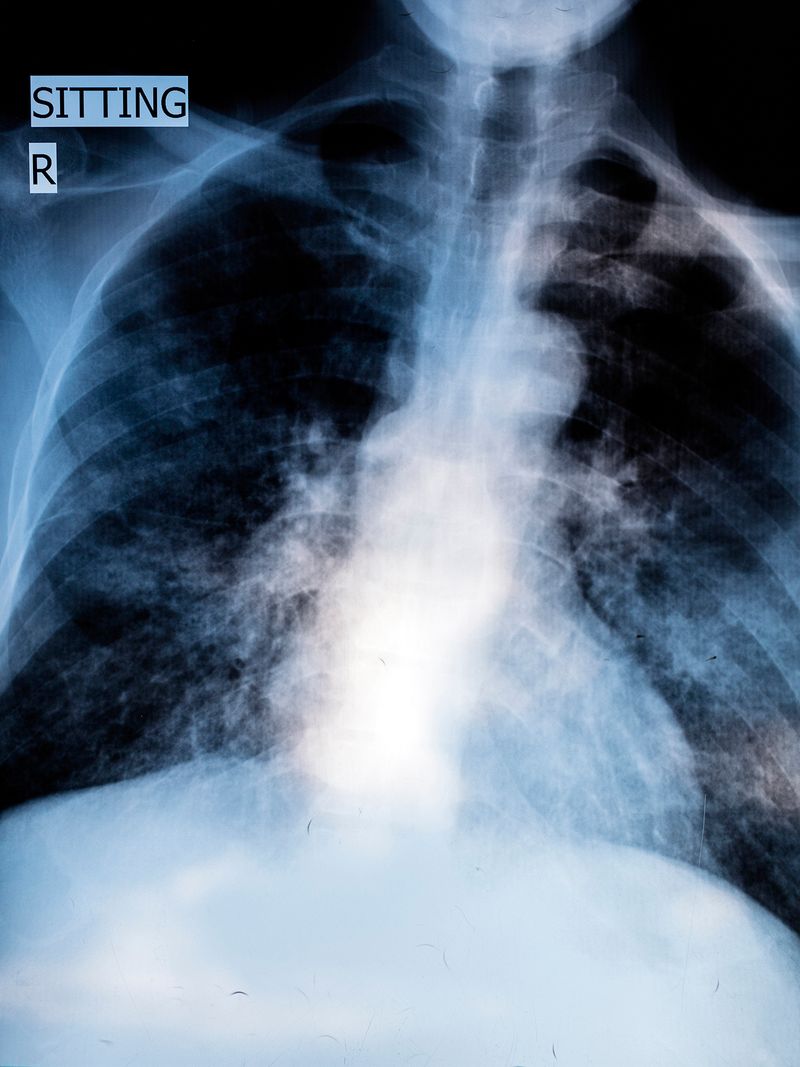

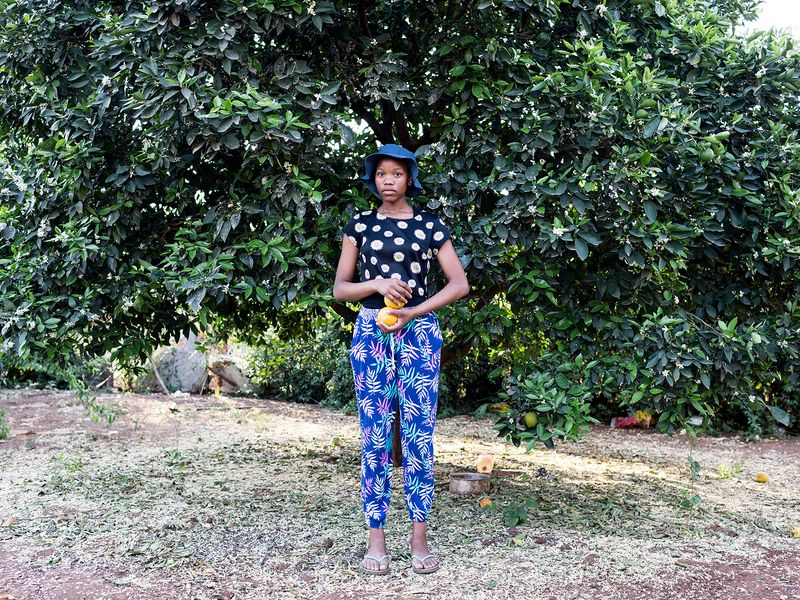

The Platinum Belt, focuses on the human, social, environmental and health impacts of platinum mining on mine-affected communities along South Africa’s platinum belt. The platinum belt stretches over more than 50 000 square kilometres and is home to 80% of the world’s known platinum reserves.

Spanning several years, my initial documentation of the mining sector in South Africa culminated in a body of work between 2011 and 2013 that would encompass a number of minerals that have directly influenced the shaping of the South African landscape. Revealing land rendered unfit for alternative uses such as agriculture and cattle grazing, a public health crisis within local communities unequipped to cope with the burden of air, land and water pollution and through the disruptive influence of historic labour exploitation impacting on family structures and cultural positioning.

South Africa has been associated with mineral wealth, both in diversity and abundance for more than a century and in recent years the demand for platinum, of which South Africa holds the majority of the world’s reserves, has grown exponentially. Platinum in particular has ignited global discussion, questioned mining practices locally and abroad and resulted in a commission of inquiry that lasted 300 days. This was the effect of public, national and international concern arising from tragic protests that unfolded at Anglo Platinum’s Lonmin Mine in Marikana on the western limb on the 16 August 2012 and led to the deaths of 34 miners gunned down by the South African police.

The work I was making during this time had a resonance, which signified everything that is wrong with the mining sector. Acting as a visual archive, a record of current mining practices, an attempt to find answers as to how one could reshape this rapidly growing industry, my photographs in and around this extractive sector have become visual signifiers for change.

With the support of a grant from the Open Society Foundation for South Africa, I returned to the north of the country in early 2016 with the aim of building on from my previous work concerned with transparency and accountability in South Africa’s mining industry by raising further awareness around the impacts of mining.

The narrative ultimately revealing an in-depth investigation into the human, social, environmental and health costs of platinum mining in South Africa, documenting the communities that have grown and bestride the Northern, Eastern and Western Limb that make up ‘The Platinum Belt’ also known as the mineral rich ‘Bushveld Complex’.

Questions are raised and directed at the platinum mining industry straddling three provinces across more than 50 000 kilometres and is home to 80 percent of the worlds known platinum reserves. It supplies around 70% of the world’s platinum.