Silence of Dawn

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Peru, Peru

To migrate is like the silence I can hear when I can't sleep at dawn. That silence when you know that the sun is rising but cannot see it yet, and you are waiting for light in the middle of the darkne

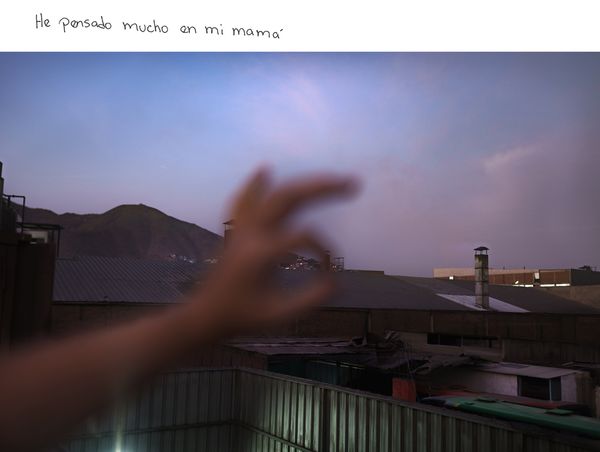

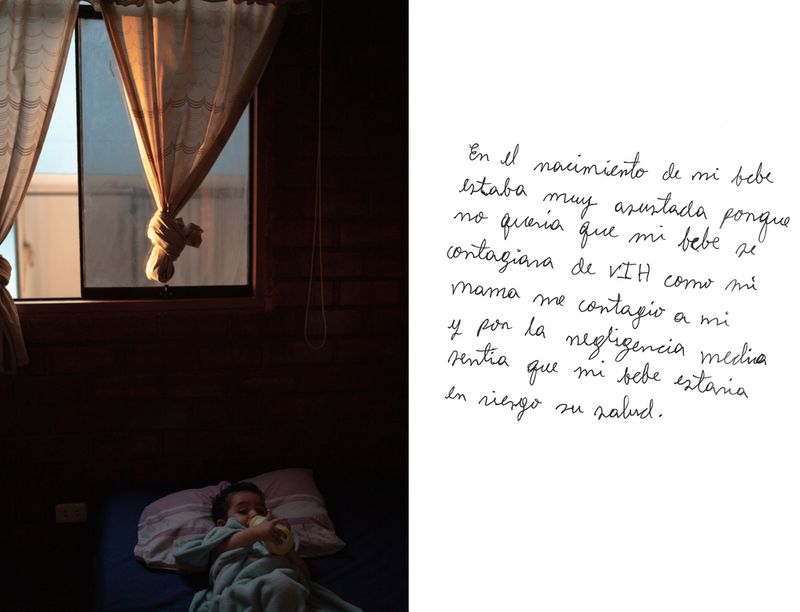

To migrate is like the silence I can hear when I can't sleep at dawn. That silence when you know that the sun is rising but cannot see it yet, and you are waiting for light in the middle of the darkness. / Yenifer Duran, 20, in Lima, Peru.

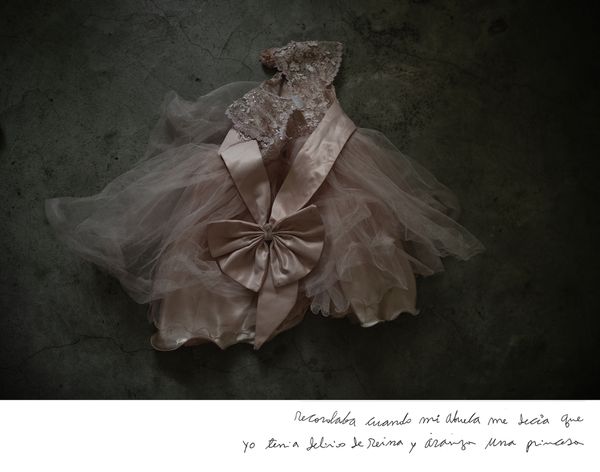

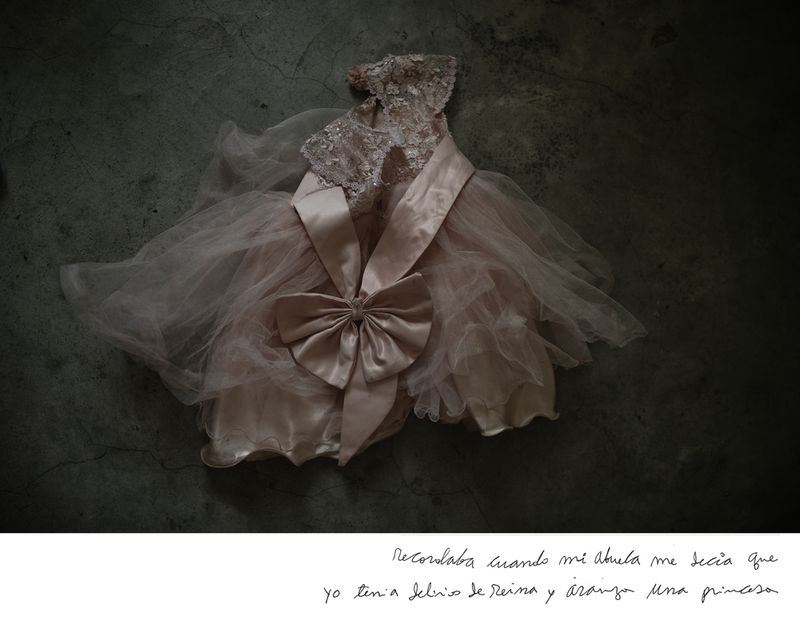

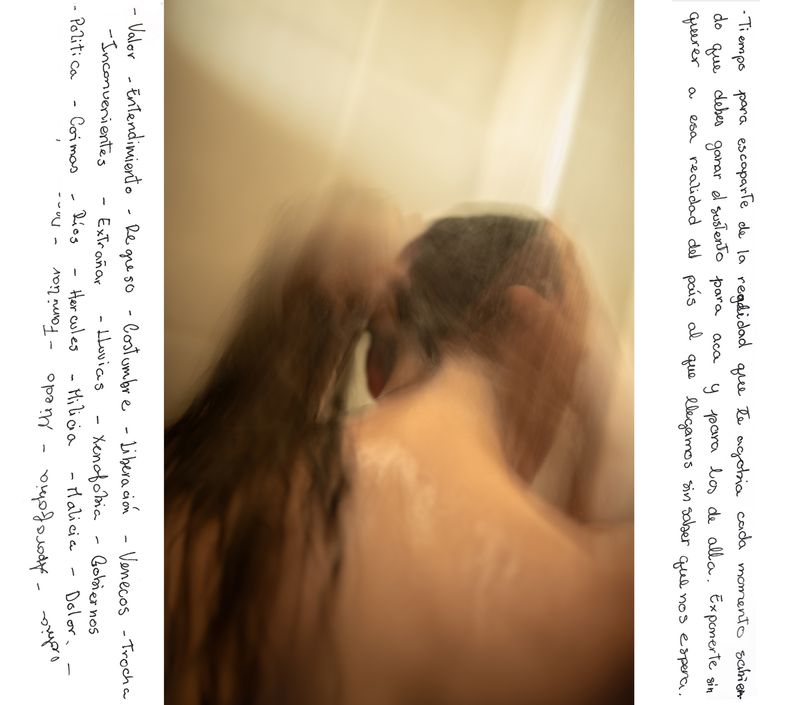

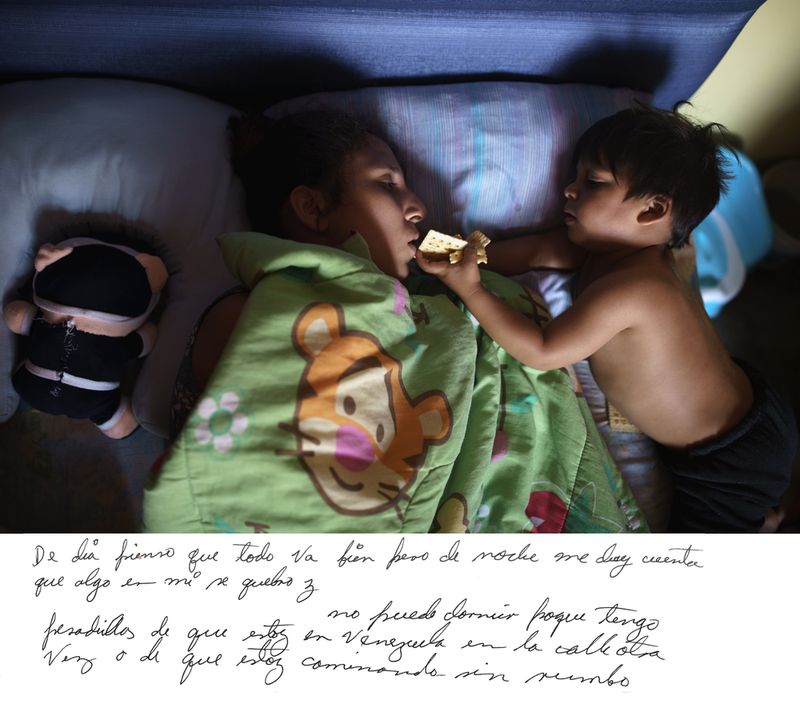

Throughout 6 months I worked in collaboration with Venezuelan women migrants who live in Lima, Peru. I was visually inspired by their stories and their memories. I wanted to look at what happened to their inner world after they arrived in Peru, how they perceived themselves within the patriarchal and hierarchical society of Lima and wanted to show the psychological and emotional experience of being displaced. I photographed their objects and spaces to convey the emotions they live with daily within their often transient spaces. From a t-shirt as a reminder of mum, a physical scar with the words that had become ingrained in their skin to past experiences turned into nightmares which kept them up at night.

In Peru, Venezuelan women experience criminalizing xenophobia differently to men. Through stereotypes perpetrated by national media, men are perceived as murderers and thieves while women are stereotyped as desperate for money, potential sex-workers and without many skills. This has casted women into informal, precarious, feminized and racialized work.

Over 5 million Venezuelan migrants live within Latin America. By 2018 in Peru, 58% were women and by 2019 most women entering the country were under the age of 30, according to UNHCR. Many of whom work informal jobs, were paid below minimum wage ($250/month) and encountered barriers for pursuing any form of education. By the end of 2020, over one million Venezuelan migrants had arrived in Peru. As of 2021, Peru ranked as the second country in the world with the highest population of Venezuelan forced migrants after Colombia. Despite UN suggestions, Peru does not recognize Venezuelan migrants as refugees with a few exceptions for health conditions such as HIV.

I will continue working on this project in Brazil as many of the women I photographed in Peru are moving back to Venezuela. In Brazil, I will focus on the gendered issues of living as a migrant under Bolsonaro with the changing political landscape as elections near. As a long term project, I will be returning to the women I worked closely with in Peru and continue with their journeys within or outside of Venezuela.