Rangzen

-

Dates2017 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Portrait, Contemporary Issues, Documentary

- Locations Nepal, Tibet, India

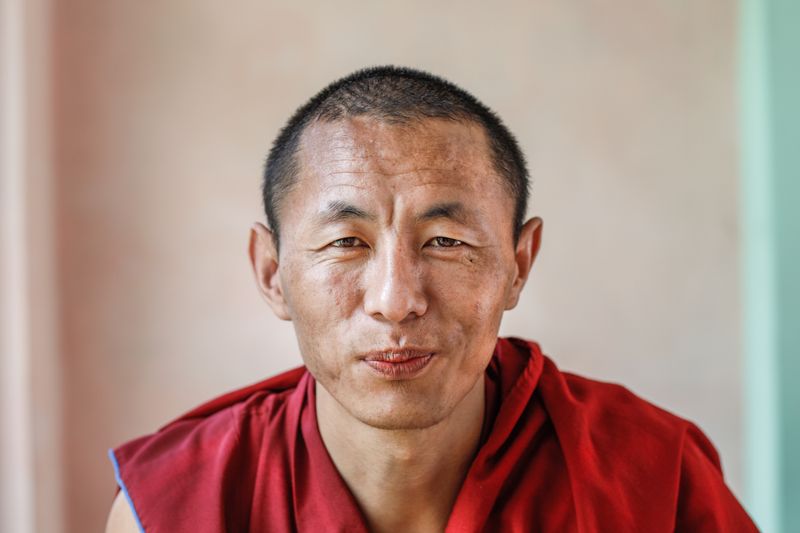

Nearly 70 years after China invaded Tibet, the generation of people who remember it 'before' is dwindling. Theirs & current stories are woven together to create an overarching narrative of the Tibetan struggle for freedom and explore complex nature of national identity for Tibetan refugees in exile

‘Remember the suffering brought by the changing times to the people of the snowland, the people endowed with history, courage and a sense of national responsibility. Remember their unflinching determination and let us continue to develop our own sense of national responsibility’. - The Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, April 30, 2000

In 1950 China invaded Tibet. The occupation that ensued was undertaken through brutal oppression, destruction and degradation with actions and policies aimed at destroying the traditional Tibetan way of life and wiping out the national identity of its people. This literal and metaphorical rape of the Tibetan people, land and culture forced thousands to flee. Many followed their leader, the Dalai Lama, into exile in India after a national uprising in 1959 during which an estimated 430,000 Tibetans were killed. Today there are over 150,000 Tibetans refugees living in exile worldwide with the vast majority in India and Nepal. China’s stranglehold over this peaceful nation continues unabated till today, threatening to squeeze out the last breath of the old Tibetan way of life.

Now we stand on the precipice of another tragedy. A more subtle and insidious one but one just as grave; the death of a generation. A generation of people who still remember Tibet before the Chinese invaded and who are still are alive to tell the stories. It is now of even greater pertinence that we capture and share these stories so that even if ‘Rangzen’ (meaning: freedom in Tibetan) is never attained; the rich, ancient culture of this peaceful country, the sense of national identity and accounts from a time when Tibet was free will not be diluted, or worse still, totally expunged.

Rangzen is an ongoing project which weaves together these stories to create an over-arching narrative of the Tibetan struggle and complex nature of national identity for Tibetan refugees in exile. It aims to serve as a document of Tibetan identity, what it means to be a Tibetan and the importance of continuing to share stories and traditions of a bygone era in order to preserve this precious identity, even in the absence of a free and autonomous Tibet. These people are Tibetan. These are their stories. Hear their voices.

I would like to return to India and Nepal to continue this work. I made a strong network of connections whilst out there shooting and researching this project. I spent a week Geshe Lhakdor, his holiness the Dalai Lama's religious assistant and translator from 1989 to 2005 who is now the Director of the Library of Tibetan works and Archive. Unfortunately, I had to leave the country due to visa issues before I was able to the photograph him for the series. I also made a connection with the son of one of the men who helped smuggle the Dalai Lama out of Tibet, I wish to go to Pokhara to the Tibetan settlement there where he lives to interview and photograph him also. I then plan to make a book, which will include limited edition prints, printed on paper made by Tibetan Refugees in exile and printed by a gallery in McLeod Ganj which is run by Tibetan refugees in exile. Then profits from the books will go to the Tibetan Women's association to the be given to their program to sponsor Tibetan refugee families when they have children, to help support the population growth and keep the stories alive in the most literal sense.