Pareidolia: Primeval Awareness or Generative Biological Intelligence?

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Pasadena, United States

Pareidolia is the tendency of humans to assign meaningful interpretation onto something; usually inanimate; so that one sees meaning where there is none. A delusion of the senses to which artists seem particularly susceptible or adept.

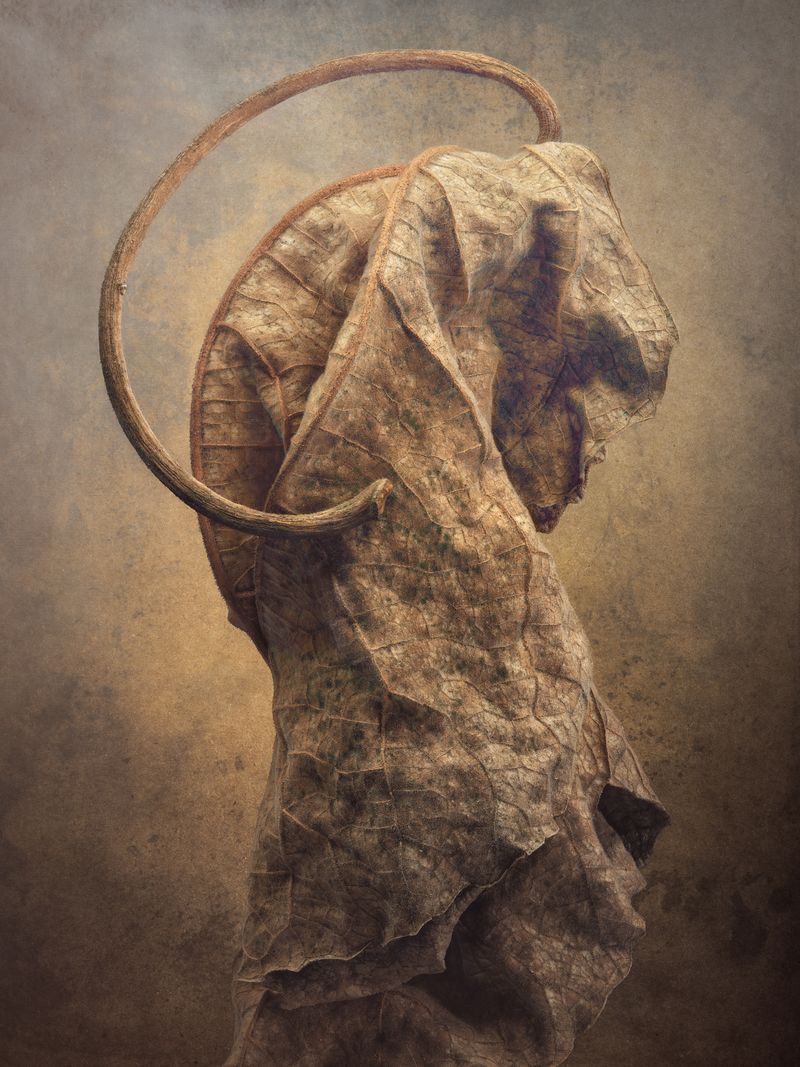

One could argue that Southern California doesn't really have seasons. But for a photographer whose main focus is the plant world, winter—the cool and occasionally wet season—is real and can be a source of frustration. As the weather changes, if at all, plants here don't go through the dramatic transformations of their cousins of temperate climes. Going up in flames being the exception. An outlier is the fig tree outside of my studio. Like all fig trees it is deciduous, dropping copious amount of leaves on a cue one can only guess. Those leaves are particularly veiny and contorted as they dry. Clutching and fondling them, one's imagination meanders. Patterns and shapes emerge. Their textures and colors at the liminal spaces between life and death, harbingers of the next stage, dirt. Yet, one cannot deny the sinking feeling that this is the same boredom induced childish behavior exhibited by those who see Jesus Christ in a slice of toast. Or is it?

The process is simple. Gather a bunch of leaves, jam them together, add a little water for malleability and start noodling. It is important to not overly think it, being careful not to force an outcome but rather let pareidolia do its thing. The exercise is to be one's own subject of study. I suspect that the more images one has studied and stored, the faster the hallucinations will manifest themselves. After all, isn't that why clients pay us creatives the big bucks? Facial pareidolia is usually the first manifestation of the hallucination. Turn the pile of leaves this way and what was once a cat is now the head of a samurai. It is at this precise moment that the conscious takes over and artistry kicks in: a sword made from a blade of grass, and his chonmage—a ponytail—a bunch of crumpled leaves. Judicious lighting exaggerating the interplay of light and dark—chiaroscuro—and a leading title along with a public reveal will suffice to pique curiosity in others and convince them that there really is something there. The results are memetic, inviting the viewer to experience what the artist saw before releasing the shutter. The resulting images are focus stacks of around 175 shots. This furthers the illusion since no information of scale; nor depth; can be deduced from out of focus cues. The process blurs the boundaries of photography, sculpture, and painting. The anatomies suggested are not believable upon close inspection, a hint that the constructions aren't fully premeditated. The images exist because of a shared selective retention that drives cultural evolution.

It has come to my attention that some may believe these images are the products of generative artificial intelligence. They are not. Currently, AI depends on prompts—inputs—to generate an image. AI (still) depends on communications skills, an emitter, the person, and a receiver, the computer. The emitter and the receiver rely on an agreed structure of communication usually conveyed by speech, writing, or gesture. The images I make do not rely on language for them to materialize. One need not be literate to experience pareidolia. Of course, most people do not spend their time toasting bread in the hope of manifesting simulacra. And if they did, God bless them, this would not fit the true definition of pareidolia. True pareidolia is impulsive rather than premeditated. It is entirely reactive, not proactive. Conversely, one could argue that to be consciously unconscious, and further more, to do it repeatedly isn't pareidolia either, demonstrating the adage that one cannot separate the art from the artist.

The resulting hallucinations seem to fall into two distinct groups: Utterly frightening or funny. Or as Charles Dickens put it, “there are only two styles of portrait painting: the serious and the smirk.” An evil witch here and a clown there. Friend or foe? Flight or fight? I remember reading that most people can recognize their own mother in a 16 by 16 pixel black and white image. Could it be that this extraordinary capacity to recognize faces—and interpret them—takes precedence over all other brain functions? After all, aren't humans the only true predators of... other humans? Does being at the top of the food chain put us in a select group of beings whose only concern is our own kind? And does this exaggerated survival skill gain prominence with age as our capacity to fight back diminishes? By twenty-first century standards, I am just beyond my prime aware that the senses that have served me well are probably declining. What was just a pair of shoes sticking from underneath the curtain are now the tip-offs of a malevolent person ready to do me in. Never mind that I had tucked my own same shoes just minutes prior. And isn't having made my business to memorize, assemble and make images now providing this sixth sense of sorts, ample ammunition to tap into and feed my delusions? The funny clown now seems to be yielding to the evil witch. Better be safe than sorry, as they say. The fear of loss is becoming more real. On the bright side, despite the trends, and despite the artist themself, I am confident that this photographer has more hallucinations and creative potential than they ever had before. Cheers to that!