Land is life

-

Dates2015 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues, Documentary

- Location Alaska, United States

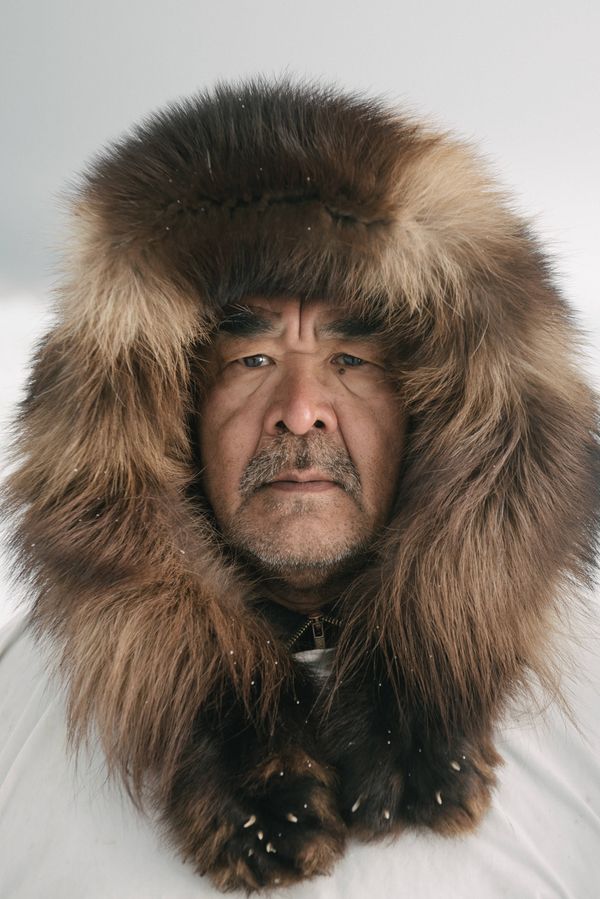

My name is Kiliii Yuyan, I am a descendant of the indigenous Nanai people of Siberia. I grew up in the US away from my culture’s homeland, but remained connected through my Nanai grandmother. I’ve spent my life learning our traditional knowledge while advocating for modern Native cultures.

The most prized National Parks in the world were carved out of highly-managed territories protected by indigenous peoples for millennia. Today, we don’t see the legacy of this colonization, believing instead in the myth of pristine wilderness without human inhabitation.

This is a savage falsehood. Indigenous people managed these lands and ecosystems long before conservation was a concept. Instead of respecting their ecological knowledge, Natives have been evicted from their homelands and their subsistence rights taken away.

Conservationists are increasingly aware of the contribution indigenous communities have to biodiversity. In regions such as Alaska’s North Slope, the government allows co-management of wildlife with Native communities. In 1977, the Alaskan Iñupiaq won the right to maintain their traditional hunt of bowhead whales and manage the population. By 2011, the Iñupiaq had quadrupled the population of the bowhead, while hunting them!

However, indigenous land management is far from universal. In 2011, the Tengis-Shished National Park was established in Mongolia in the territories of the Dukha, who are reindeer herders. Inside the National Park, hunting and reindeer herding are prohibited. Without reindeer, hunting, or legal recourse, the Dukha community are increasingly forced into settlements and driven to alcoholism.

Approaches that have trusted indigenous peoples with land management have seen benefits. In 1991, in the Brazilian Amazon, the Ka’apor Indians were given the legal rights to the enormous Alto Tuiracu Indigenous Land. Today, after 25 years of massive deforestation of the Amazon, deforestation has slowed dramatically as loggers reach the borders of indigenous land. The Ka’apor take defense of their lands seriously, and are known to aggressively confront illegal loggers, even beating repeat offenders.

Project and Creative Approach

I spent three years living on the Arctic sea ice with Iñupiaq whalers, sharing the watch for polar bears and eating fermented walrus. My series, People of the Whale, was born from the experience of being part of the crew with a shared Native ancestry. I began to understand the complex Iñupiaq relationship with the whales they sustainably hunt. The story of the Iñupiaq is a vision of successful conservation using indigenous knowledge, but many communities that have not been as fortunate.

In Western Mongolia, conservationists have evicted the Dukha from their traditional lands. My colleague Gleb Raygorodetsky is from the nearby Altai and will introduce me to local residents. The Dukha have become increasingly dependent on tourism, making access easier. I believe the best way to learn the story is to live with the Dukha for six weeks, and accompany the National Park rangers over time.

In the Brazilian Amazon, the Ka’apor are at war with illegal loggers and ranchers. My friend Miguel Iglesia, living in the Amazon and married to an indigenous Achuar woman for a decade, has helped me to understand that the Ka’apor believe they will lose everything if they lose their forest, because their way of life depends upon it. I plan to embed with one of the Ka’apor patrols for a month, who work in concert with the regional police. The Ka’apor have currently extended an open invitation for foreign journalists to report on indigenous issues.

The answers I seek from the Ka’apor and Dukha: How do you see the natural world and the place of people within it? How do you manage the ecosystem even while gathering its resources?

Engaging Audiences

The most important result of this project is putting the photographs in front of the youth of these communities and give them pride in their indigenous identities. My interactions with Iñupiaq youth have resulted in some seeing the subsistence life as positive for the first time. I return to my communities over the years, and speak to youth about tradition, identity, and relationship to the land.

This project will result in a photo story for National Geographic Traveler China, and I am in conversation with my editors at National Geographic Magazine as well.

Finally, I will engage online platforms with video. I created a short film of the Iñupiaq relationship to the whale and sea, and intend to do the same for the Ka’apor and Dukha. I envision a multimedia story on Topic.com and a series on Instagram.

Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize Laureate, wrote: “Every culture that disappears diminishes a possibility of life.”