In Hadar Going Nowhere

-

Dates2021 - 2021

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues, Contemporary Issues, Documentary

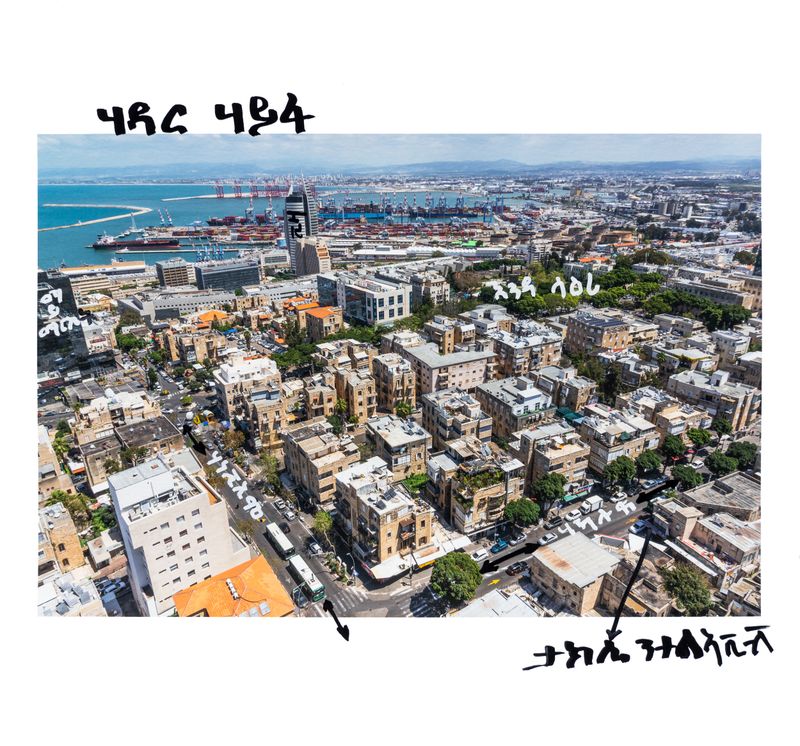

- Location Haifa, Israel

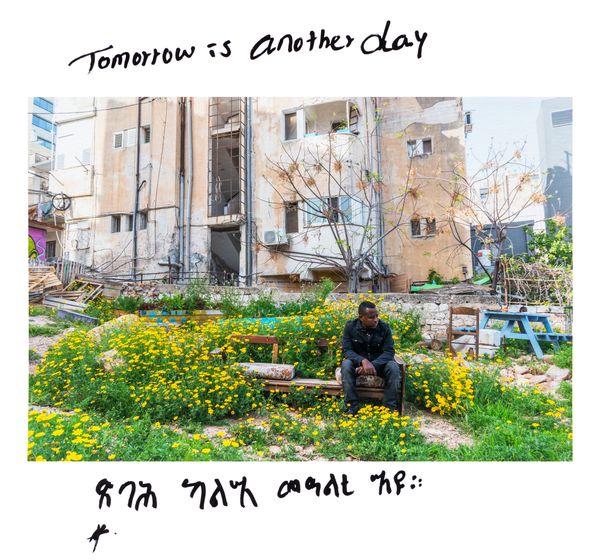

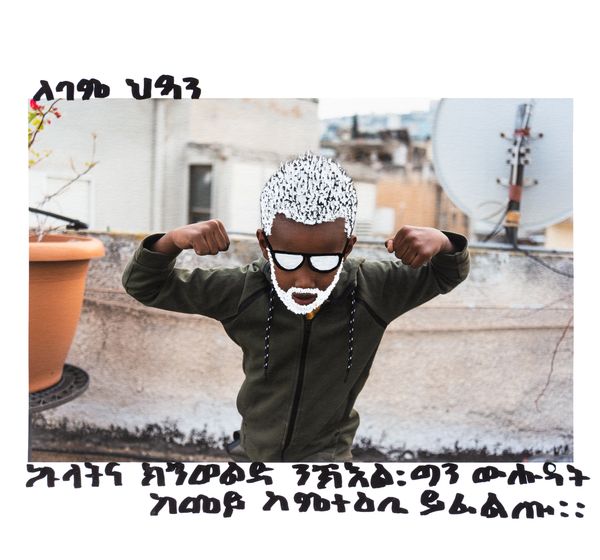

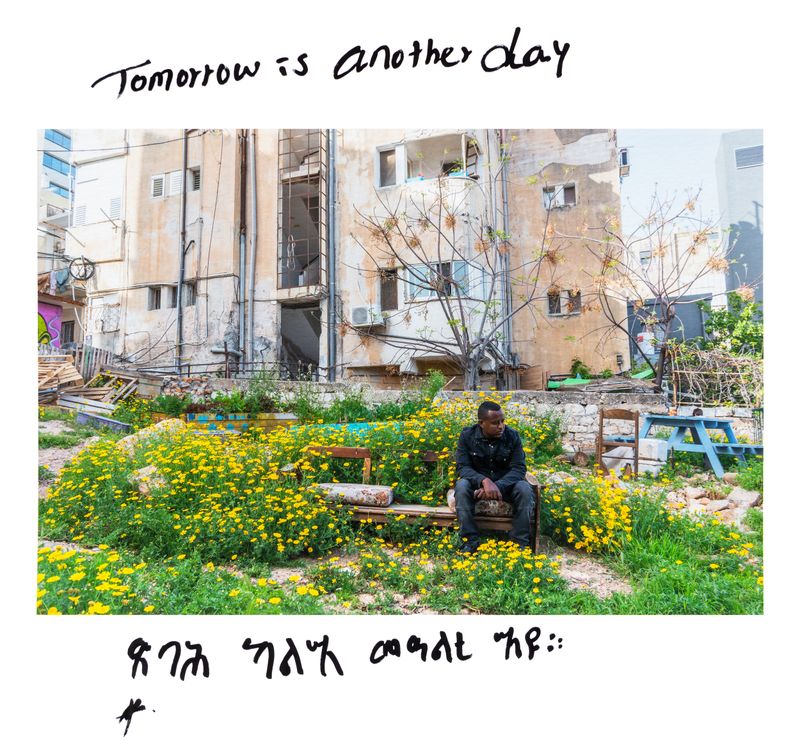

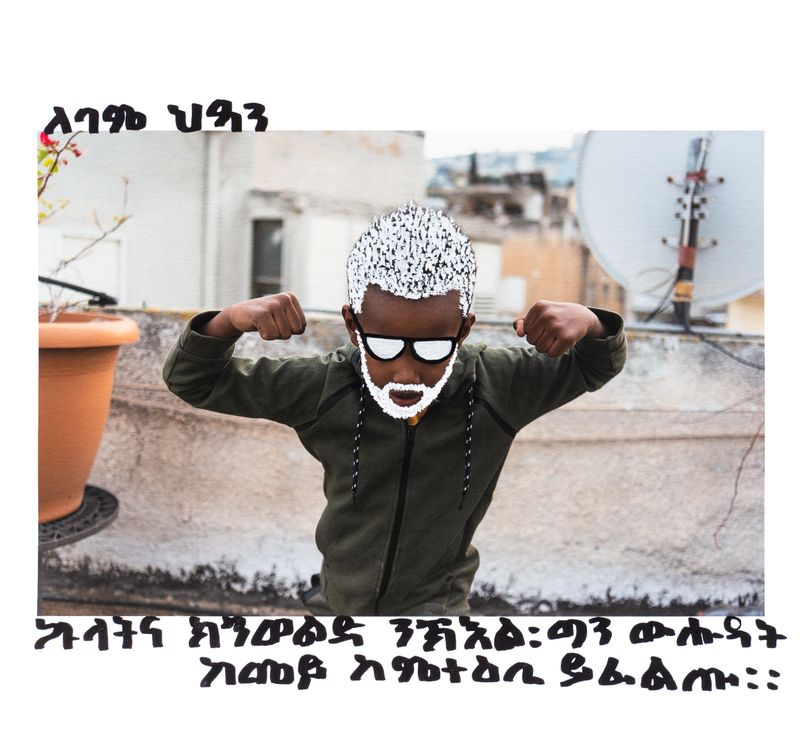

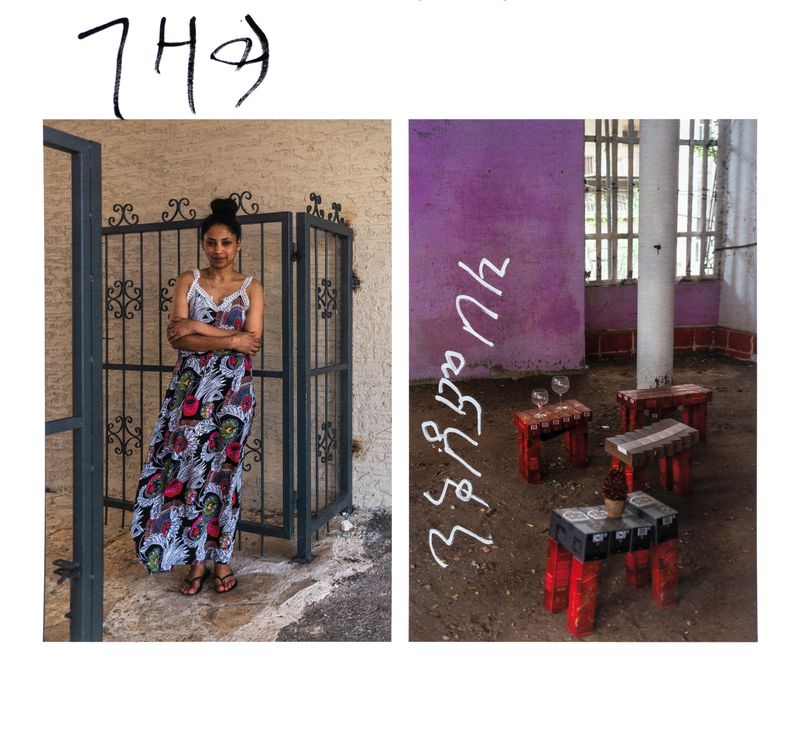

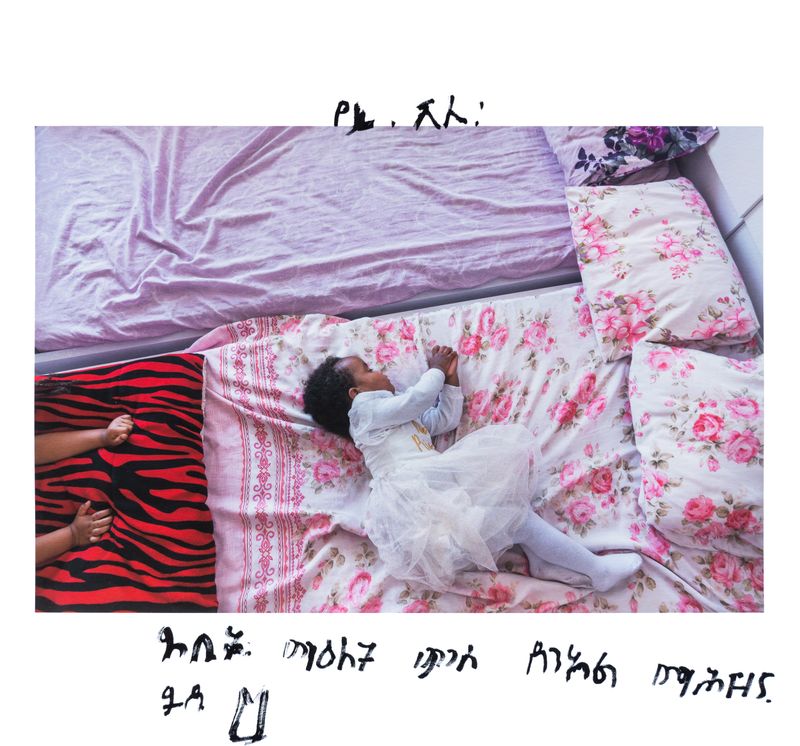

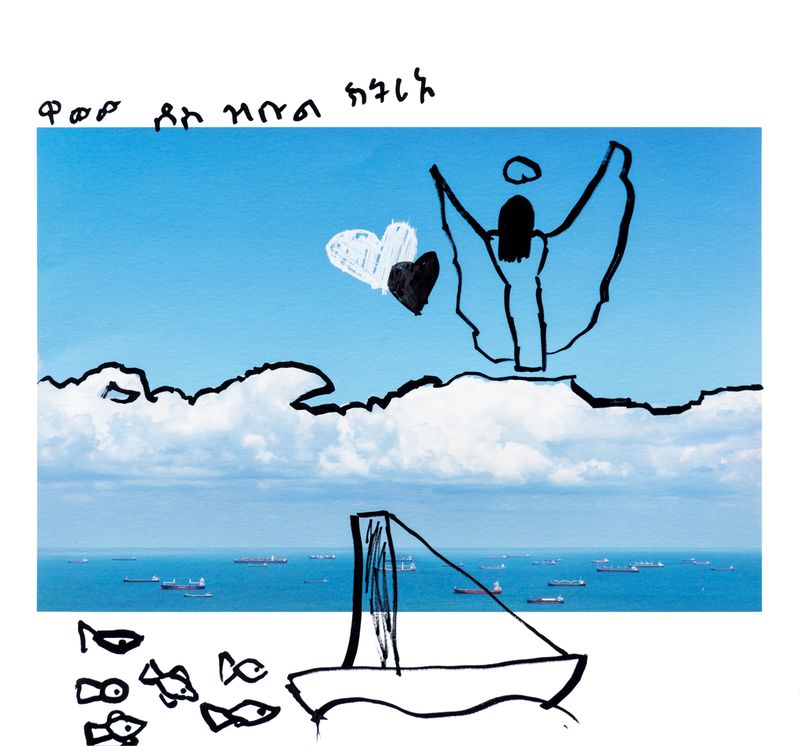

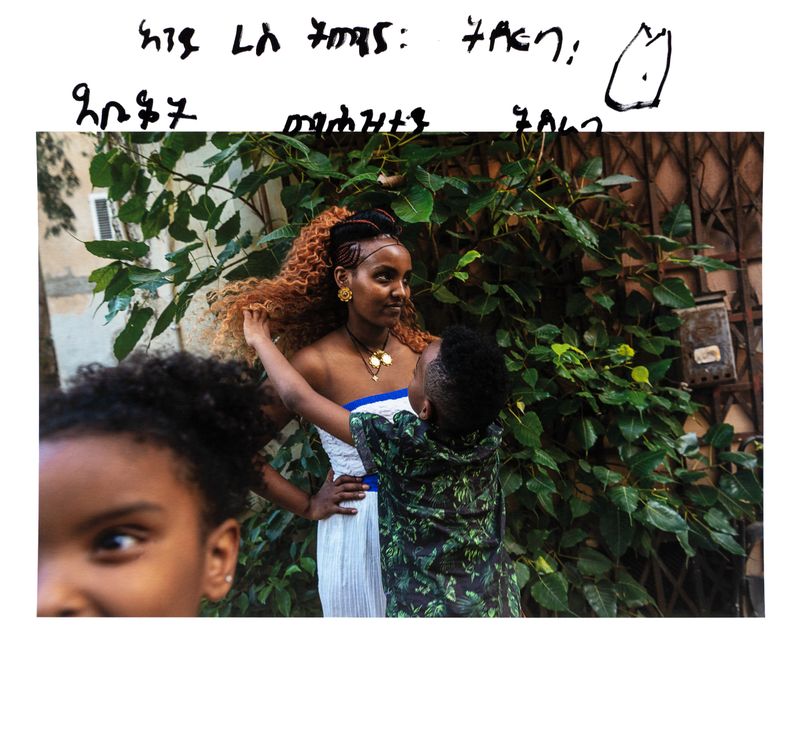

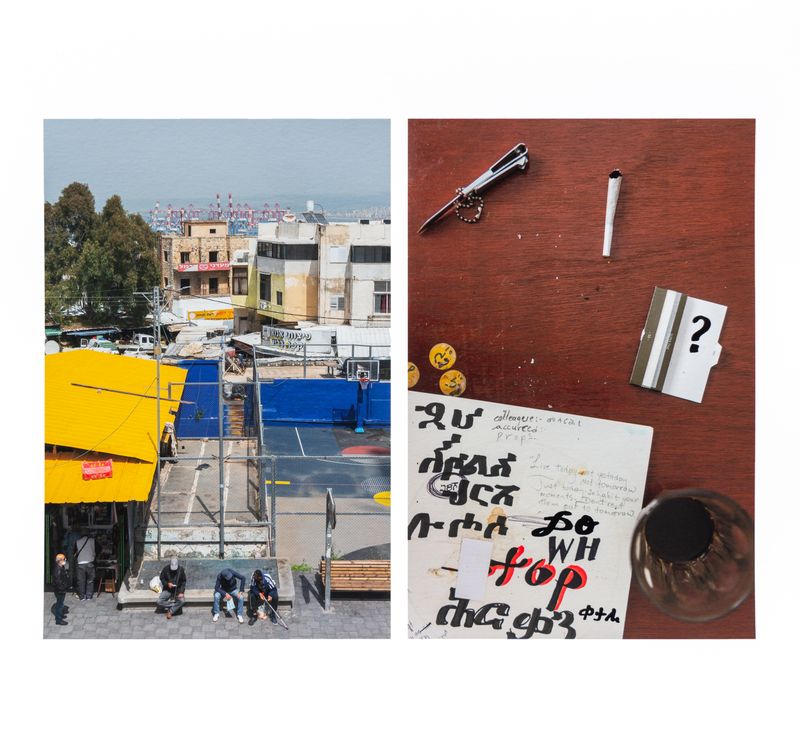

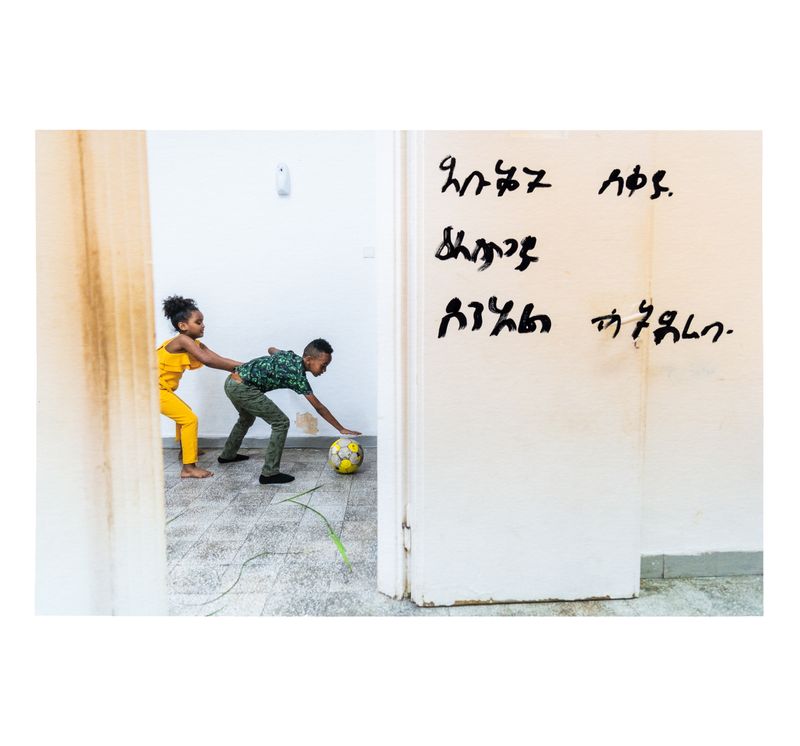

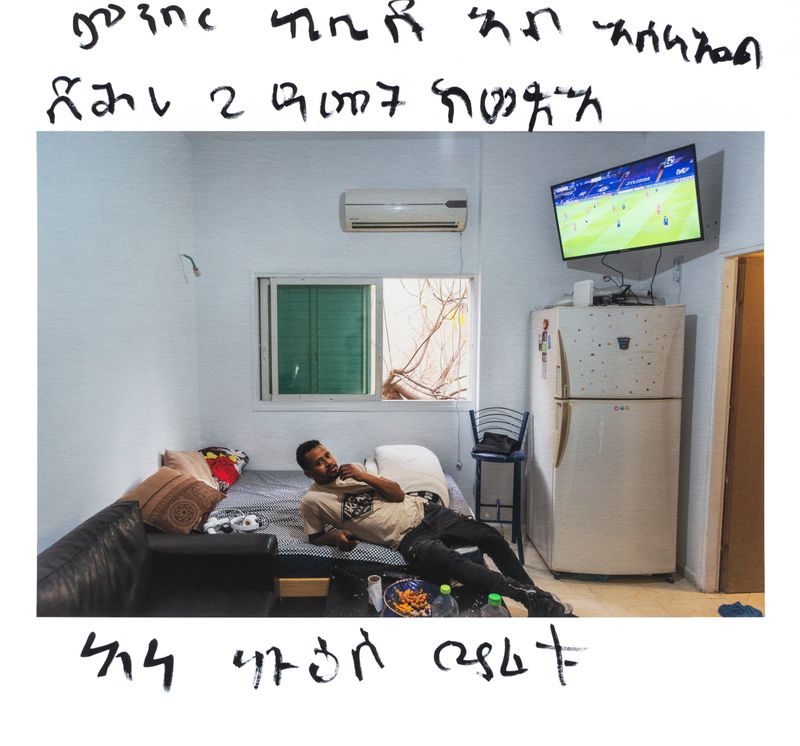

A combination of documentary photography and written dialogue from men and women, single and married, from the Eritrean asylum seekers community in Haifa, Israel.

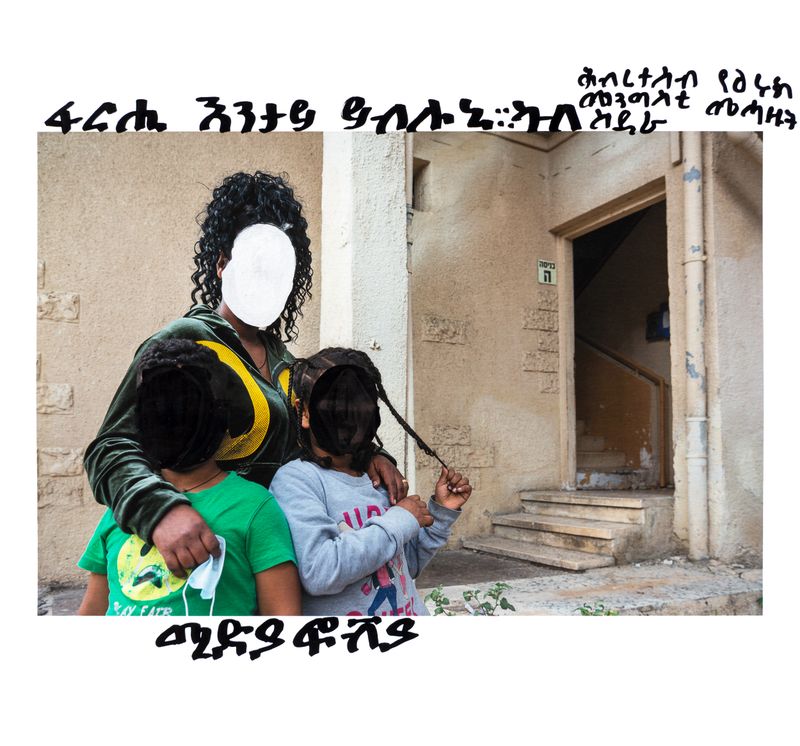

In the Hadar neighborhood of Haifa, in old houses that are now only remnants of a golden age that has long passed, lives a community of Eritrean asylum seekers. Between 500 and 700 Eritreans live in Hadar, one of Haifa’s poorest neighborhoods, out of approximately 21,000 currently living throughout Israel. They live under the radar without basic rights, such as access to healthcare and welfare services, in an endless limbo. On the one hand, Israel cannot deport them due to international laws that grant protection to individuals who meet the consensus definition of a “refugee”. On the other hand, the government has not been approving asylum applications for Eritreans. By combining documentary photography with written dialogue from men and women, single and married, from the Hadar community of Eritrean asylum seekers, this project aims to shed light on the harsh reality that they have been forced into, as well as the reality they created for themselves.

Most asylum seekers in Israel crossed the Egyptian border between 2007 and 2012 and arrived in the “Promised Land” after fleeing a dictatorial regime that denies its citizens basic human rights. They escaped poverty, hunger, and indefinite enlistment in the Eritrean army where they were subjected to inhumane conditions, including hard physical labor and sexual exploitation. The reasons Eritreans chose to escape to Israel vary; some thought that they would be welcomed with open arms in light of the history of persecution amongst the Jewish people, or because of their deep religious connection, while others were abducted by Bedouin smugglers and forced to cross the border. Today, in order to survive, they are forced to work long hours in exchange for meager wages without the ability to leave the country and get a driver’s license.

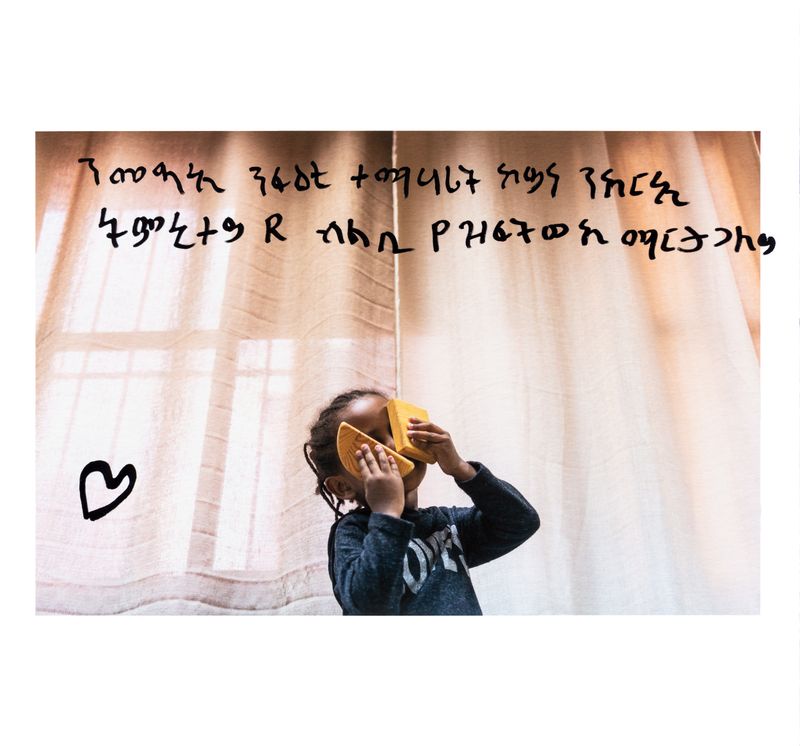

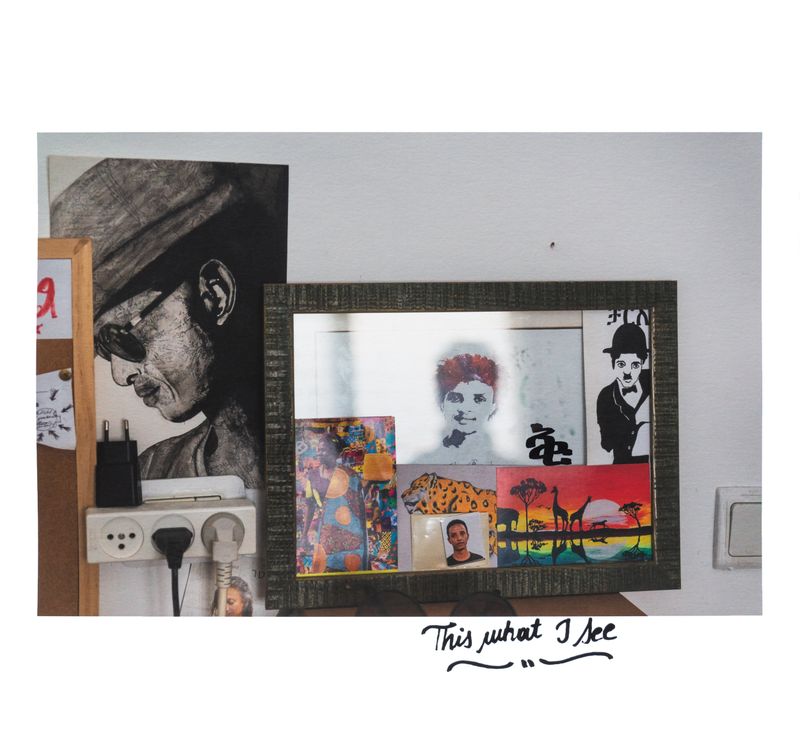

Through interviews and photographs of the Hadar neighborhood, Eritrean asylum seekers told their story. Even years after leaving their homeland in East Africa, many Eritreans were afraid to openly expose themselves and their story. While they fear the reaction of their family and community, their main concern is the physical and economic harm that the Eritrean government might impose on their loved ones who were left behind. According to sources in the Hadar community, their government continues to track its citizens’ activities abroad to ensure they are not damaging its international image or empowering its opponents. To ensure their safety and form a platform for self-expression, the photos were printed and given to those photographed. While some chose to write their thoughts, feelings, and messages on the pictures, others decided to paint on their faces - and hide their identities.