Dead Water

-

Dates2014 - 2018

-

Author

- Topics Social Issues, Documentary

‘Dead Water’ is a collaborative visual storytelling project about an issue of global concern: the socio-environmental impacts of hydropower.

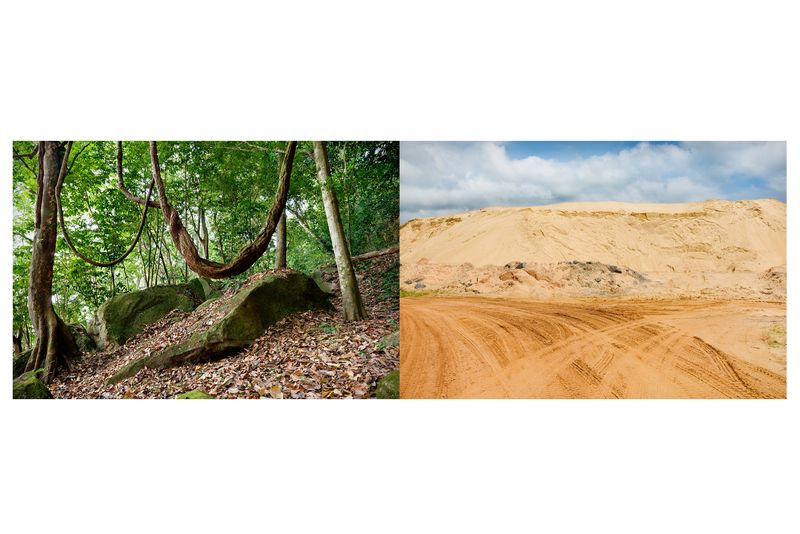

‘Dead Water’ is a project about a place of access, connexion, flux. Despite using material processes, the focus is not on physicality. It is about the transit between the river (the material site) and the other river (the site of life, of wealth, of beauty, of belonging, of identity, of memory, of democracy, of the transcendental). Rivers that join within the space of this work: the territory of the encounter, the space where exchanges between subject and photographer happen.

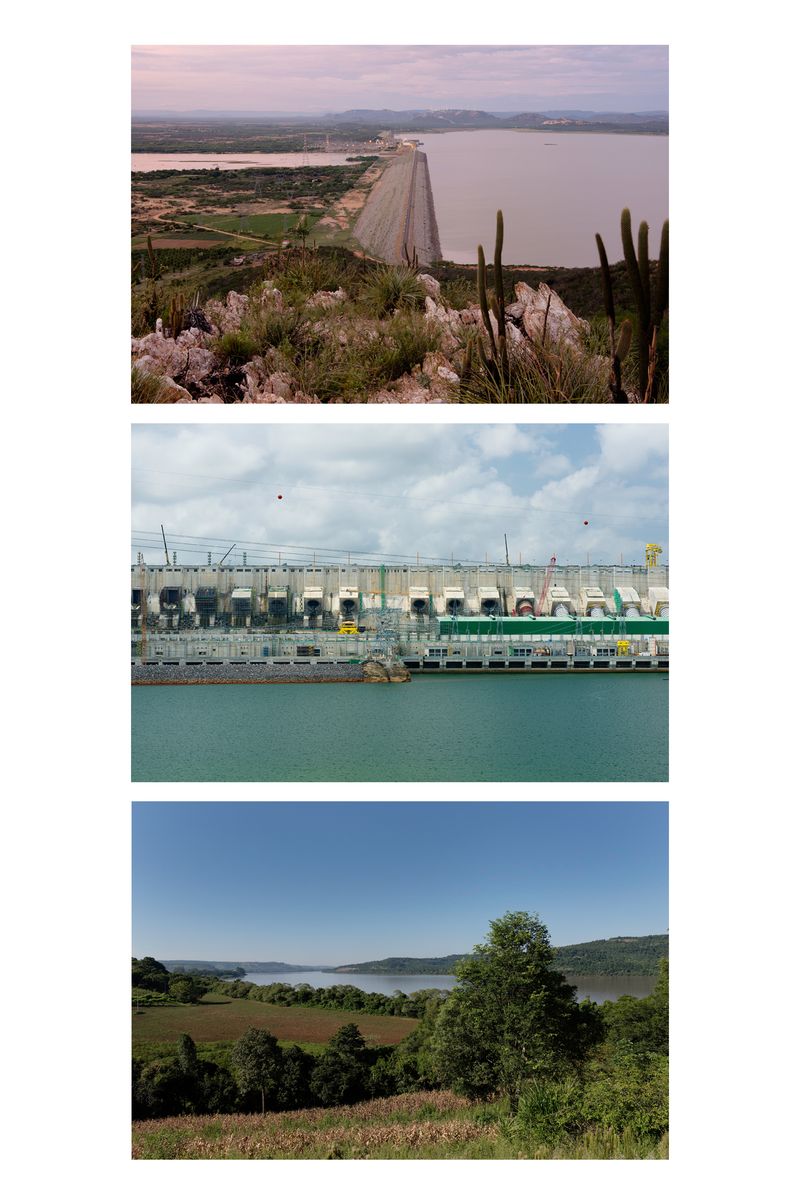

‘Dead Water’ (2014–2018) is focused on telling the story of dams and hydropower from the perspectives of the people who have been affected by these ventures in Brazil stitched together with my own background as a trained photographer, ecologist, and individual. I use Brazil, my home country, as a window to discuss a contemporary issue that has, in fact, involved many countries and that tackles the climate change agenda. ‘Dead Water’ engages with the nature and magnitude of the intangible costs of dams and hydropower, as a counterpoint to the widespread notion of hydropower as a "sustainable and green" energy source that promotes development and fights global warming.

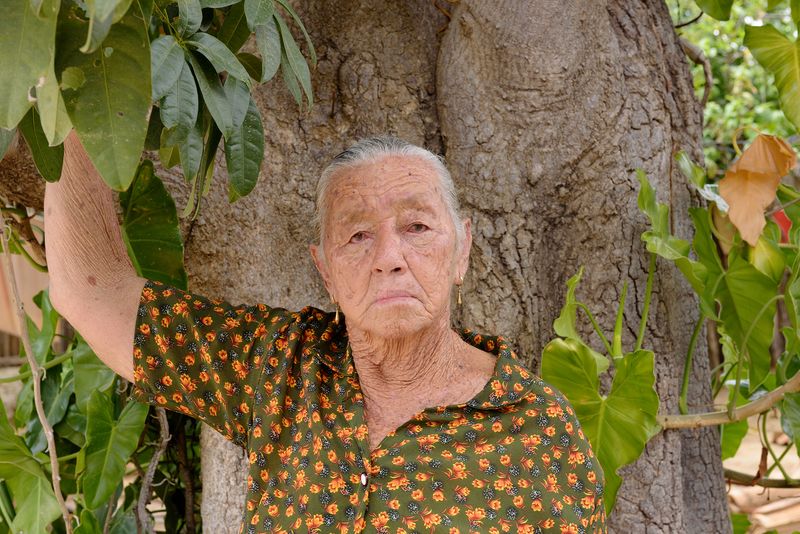

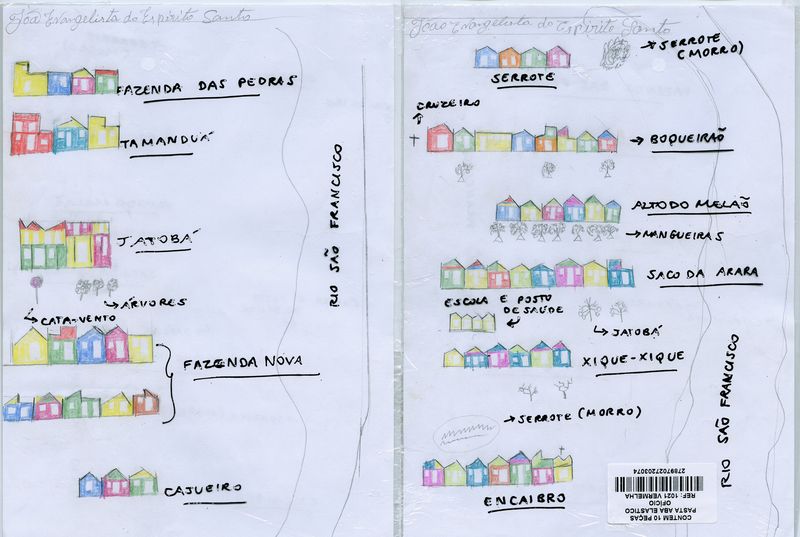

It made sense to me to explore the act of damming a river through the experiences of those who I consider the most appropriate ones to speak about this subject: riverside dwellers. As such, I looked for and invited individuals who were displaced by the construction of the Sobradinho dam (which was built forty years ago, on the São Francisco River, North-eastern Brazil) and Belo Monte dam (whose construction was completed last year, on the Xingu River, Amazon region, Northern Brazil), and also dwellers who might be relocated due to the Garabi-Panambi dam complex (planned to take place in near future, on the Uruguay River, Southern Brazil) to sit for a portrait. For this photo shoot I asked these sitters to choose a relevant place, as well as to select an object that could represent the feeling(s) they had with regard to the hydro project. During the shoot (in which I was in charge of operating the camera), I encouraged participants to come up with their own ideas for their own portrait and they could also check and modify the ‘framed scene’ until they considered the image they saw on the display of my digital camera tallied with what they wanted to present to the viewers. At the same time, by gathering further information and images with participants, we tried to reconstruct sentimental landscapes of their loss. Moving from north to east and south, from the Amazon to the Atlantic Forest and the semi-arid Caatinga, from the first dam scheme in 1971, towards nowadays and somewhere in the future, participants and I shaped a hybrid perspective: the subject and the photographer worked together. The 96 participants of this project and I assembled stories that are intended to set out a narrative about the magnitude of damages that hydropower has inflicted upon nature and people, and also to enable these submerged perspectives to surface.

* This work was undertaken with the vital support of the Brazilian Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB), and with the financial support of the CNPq and the Royal Photographic Society.

An overview on the Dead Water project can be found at: https://www.marileneribeiro.com/dead-water

and https://www.marileneribeiro.com/dead-water-book

A video of the hardcopy of the Dead Water book dummy can be accessed at:

© Participants and Marilene Ribeiro