What Objects Say About Us

-

Published17 Mar 2022

-

Author

In daily life, objects are often overlooked. Devoid of any sense or emotion, they live a life of stillness, unchanging aside from their inevitable discoloration that comes from exposure to sun or their declining functionality due to repeated usage over time. But that’s just their appearance.

In reality, they offer a story—our story, or those of other people. Ultimately, they symbolize the tangible aspects of our existence: our needs, demands, desires. They can be useful or ornamental, charged with sentimental value.

“Objects tell us more than we estimate them to,” says Chingrimi Shimray, photographer from India. Her project, Our Belongings, is an ode to these objects, their very existence and essence.

For more than a year, Shimray has photographed people—neighbours, acquittances, relatives, friends—but indirectly, by focusing on the objects they carry. These lifeless items become the main focus of her work—and they speak. They tell stories.

“There is a relationship that we start to form unknowingly with the things that we keep in our homes or even things that we take with us on a daily basis,” Shimray says. “There are so many things that objects tell about us.”

As Our Belongings started taking shape, Shimray looked around carefully for things that caught her eye. Objects suggest a tacit hierarchy, which humans intuitively recognize. Some objects also become more noticeable or indispensable for the cultural significance that people attach to them.

Shimray solicited a participatory approach with the people she photographed, seeking an authentic bond between them and the objects they carried. Some objects had been with the participants for a long time, and some were newer acquisitions. Some were bought, gifted, or traded. Some were handmade.

The fishing net had been hand-knotted by Api, Shimray’s grandmother, during her stay in Marou. It’s an important tool in her village, employed in daily activities, trade, and community life. In Shimray’s depiction of Api holding the net, the object comes to life in a playful sequence of frames. Api places it over her head, transforming it briefly into an oversized hat that covers her hair. Then, paintbrushes are applied to a photo, giving a cartoonish edge to a single moment in time, as the color of the brushstroke the elements—the unfilled space, the basket, the woman. Finally, it’s transformed again into a moving film sequence, half fictional and half real, as a yellow fish rises to Api’s ankles. Some fish have been caught in her net. Api smiles.

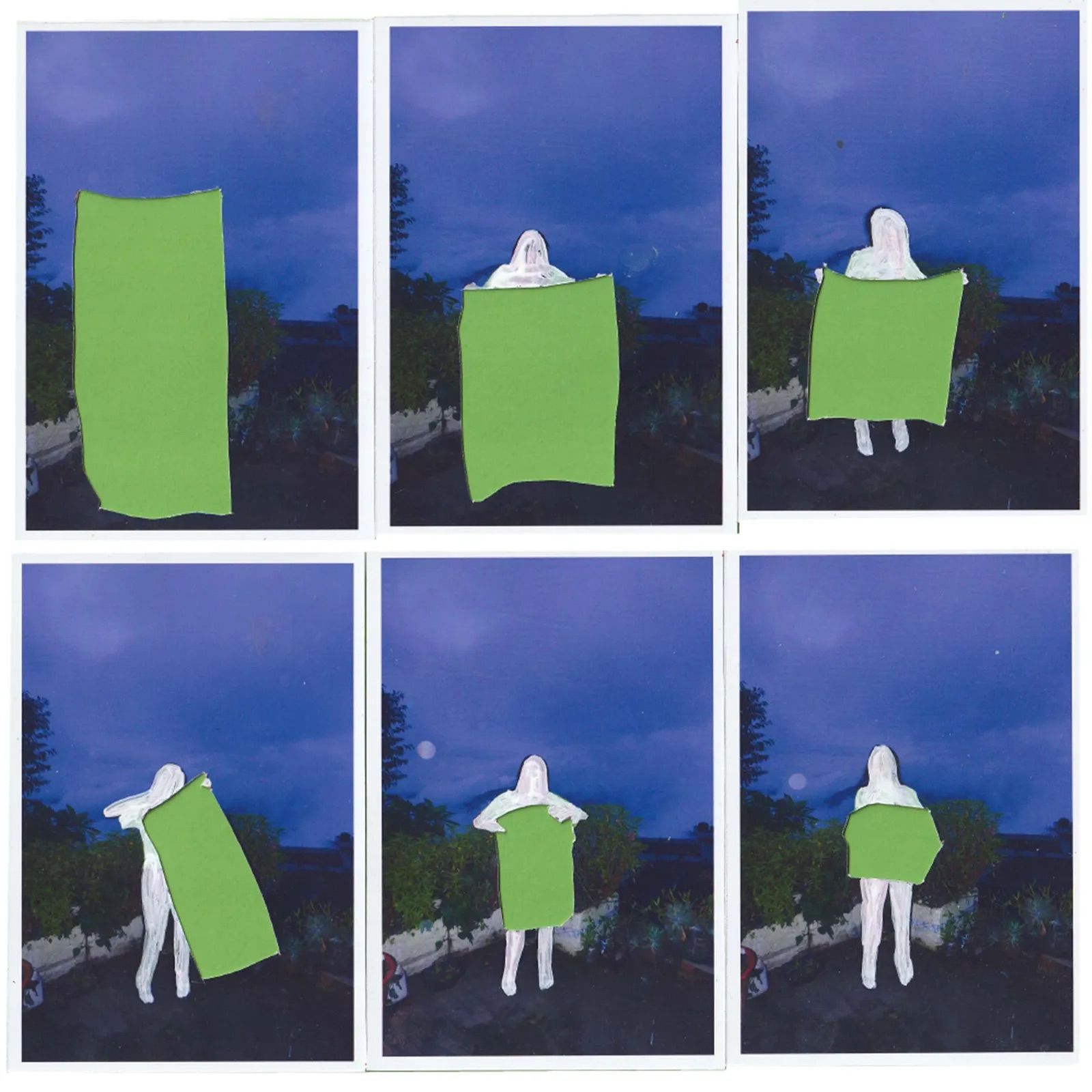

Another photo shows a handwoven blanket made of old sweaters, a meticulous work repurposed from unconventional textiles, common in her village tradition. Centring the blanket in the frame, Shimray shows it wrapped around a person, hiding the figure beneath it. It’s a common object, endowed with greater value, a sense of the tradition and cultural heritage it embodies.

“Objects are a way of talking about my community,” Shimray adds.

The emphasis placed on the meticulous practice of knitwork emphasizes the authenticity and work ethic typical of a simpler culture.

“It talks about the kind of socioeconomic conditions of the people back then, or just the way of life, the culture during the eighties,” Shimray says. And here, a bigger resolution is revealed: a different perspective emerges, new narratives that empower indigenous storytelling.

In some frames, the blanket becomes two-dimensional, painted in vivid green. This act of “extracting” the object from the image aims at exploring what happens when our belongings are taken out of context.

“If you take an object away from its natural state, it changes the story, it takes a piece of your history away.” This is Shimray’s interpretation, but she holds space for the viewers to express their own.

“This whole project was a way to rediscover the way I look at my own community,” Shimray says. “I haven't figured everything out about my community, and I'm still in the process... Photography is one of the ways in which I think I'm enjoying it as a process.”

All photos © Chingrimi Shimray, from the series Our Belongings

--------------

Chingrimi Shimray is an Indian artist and photographer. She's based in Ukhrul, Manipur, India. Find her on Instagram and PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer focusing on photography, illustration, culture, and everything teens. She lives in New York. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

--------------

This article is part of the series New Generation, a monthly column written by Lucia De Stefani, focusing on the most interesting emerging talents in our community.