A Kingdom where Power Rules, Power Corrupts, and Power Destroys

-

Published24 Oct 2018

-

Author

Spanish resorts, patrician speeches and crumbling concrete make Txema Salvans' latest book one that works on multiple levels.

Spanish resorts, patrician speeches and crumbling concrete make Txema Salvans' latest book one that works on multiple levels.

Take a knife to the skin of a successful photographer who makes their money from their commercial work, make a little nick, and 60% of the time, out will flow the blood of a frustrated artist. Sure they make their money from photographing this or that, but at heart they want to be an artist. But where do you get your ideas from? What do you do if you’re an artist? Isn’t it all terribly difficult?

Inject a truth serum into the veins of a successful photographic artist who, let’s be honest, does not really make much of a living from their art, and yes, they confess, they’d love to make a living wage, go on a beach holiday, buy some new clothes, go out for a meal once in a while. Photograph interiors, products, a lookbook, a wedding, they’d love to. But how exactly do you go about doing that? Isn’t it all terribly difficult.

That’s a bit of a harsh division, but we’ll go with it because it is so simple and essentially true (except when it’s not).

So you have your artists and you have your people who are able to make money – which is an art in itself and not to be sniffed at. But let’s divide those photographic artists into those able to make photographs and those not.

Most photographic artists can’t take a picture to save their life. Photographic art in the more conceptual sense is rarely about ‘great pictures’ that stop you in your tracks and make you wonder at the stories that are unfolding within the frame. Most photographic artists aren’t able to take a good picture, let alone a great one. That’s why you have so much photographic theory, much of which is to justify why these rambling, amorphous projects are actually really important and often made by the theorists who write to elevate what they produce.

Again, that’s a bit of a harsh division, but we’ll go with it because it is so simple and essentially true (except when it’s not. I’m thinking of all the examples where it’s not true, but what the heck, we’ll go with it).

‘Great pictures’ are far too simple a pleasure, and they do involve pleasure. They involve the luxury of the spectacle, they embrace the pleasure of looking, the simple joys of being a voyeur. And if you’re interested in looking at pictures, then a voyeur is what you are.

And of course voyeurism is a problem. In much of photography, there is an overwhelming discourse of sobriety, the idea that when you talk about photography, you write about photography, it is with a heavy heart and a sombre voice, and you use the word ‘problematic’ a lot – that’s how important it is. It is allied to the Calvinist notion that for artistic salvation, one’s works must be a penance to write, to make, and ultimately to read about.

The problem with the idea of ‘great pictures’ is as a photographer you are essentially a voyeur, pleasuring your voyeuristic viewer with your voyeuristic pictures. And pleasure is associated with the trivial.

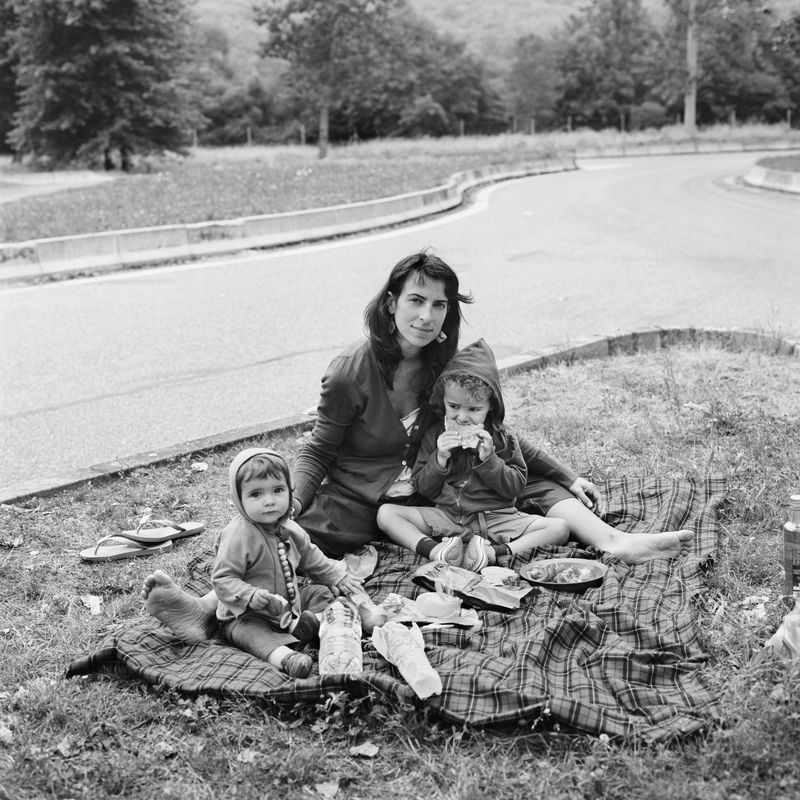

That seems to be the case with Txema Salvans' My Kingdom, a book for which he made phenomenal pictures. It’s a pleasure to look at, but that for Salvans is not enough. My Kingdom is a book of images of Spanish holidaymakers enjoying a day at the beach. When Martin Parr made The Last Resort, he first and foremost made a book of great pictures. There’s a bit of The Last Resort, Spanish style, about My Kingdom.

But there’s a different edge to them as well, a political edge, a bit of Chris Killip if you like, mixed with Ricardo Cases and his Spanish perspective. My Kingdom shows Spanish holidaymakers enjoying their days off against these specifically measured examples of Mediterranean brutalism; flyovers, bypasses, power plants, cement works, pipelines, balconies, apartment blocks, rubbish bins, discarded mattresses, all the detritus of a despoiled, constructed landscape.

If you have any doubts about where he’s coming from, there’s also an affectionate dedication to those who he photographs that very beautifully defines the book: "Dedicated to all those who live with simplicity and honestly beyond the empty words of speeches intended to imprison us, and to those who know that life is not lived behind a flag but in the fraternity of ordinary people enjoying the sunshine on a warm day."

The thing about great photographs is that embedded within them, sometimes with the conscious knowledge of the photographer (with Salvans for example), sometimes not, are the more complex layers that tell us something that goes beneath the surface. And when you have that, what more do you need. The world is there to be read, how much do you need to spell it out.

In My Kingdom Salvans spells it out in large letters. There is that dedication to the idea of leisure as resistance, that you can expand to the idea of idleness against enforced labour, idleness that has been subject to both persecution from the past (the ‘workshy’ were marked by black triangles in Nazi concentration camps) to the present day. My country is waging psychological war against the ‘undeserving’ poor and disabled that has resulted in thousands of deaths by suicide.

So My Kingdom has a political edge added. There are, written in large teleprompter typeface on black pages, words from the Spanish King’s Christmas speeches. They reek of patriarchy and privilege, they pronounce a shared experience that runs counter to the lives of the people shown in the book, but in parallel with the land in which they lie.

Political and economic power, and the language of that power are intertwined then. It’s the Kingdom of the title. But at the same time, the small spaces, the idea of these little subversions of pleasure, of doing nothing stand as a counter kingdom, all the personal kingdoms that are enacted on these patches of sand and grass, where the food, the towels, the view, the simple sensation of the sun on the back can be a simple stand. In Salvans’ world, pleasure that has not been commodified is a political act.

I started off this review thinking how some of this politicisation was excessive or unnecessary, how the book was an example of a really great photographer seeking to artistically gild his work with the added value of a commentary on commodity fetishism of the everyday. But then I wondered and thought again. There is the idea that in photography today there is no room for ambiguity. That is what Salvans is doing in My Kingdom, he’s removing ambiguity. His is a Kingdom where power rules, power corrupts, power destroys. But power isn’t life, and life is created through the moments, the pleasures, the acts of being that don’t belong to any ideology, religion or fall under any flag. And there’s no ambiguity in that.

--------------

My Kingdom by Txema Salvans

Published by MACK in August 2018

OTA bound paperback with silkscreen printed cover and flaps. With stapled booklet and postcard

176 pages // 65 tritone plates // 17.5 x 23 cm // $40

--------------

Txema Salvans is a Catalan photographer born in 1971. Throughout the past two decades, Salvans has developed a documentary approach outside of the traditional photojournalistic narratives, producing photo essays that balance critical thinking and a poetic sense of humour. Follow him on Instagram.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest book, All Quiet on the Home Front, focuses on family, fatherhood and the landscape. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.