A Tender and Emotional Portrait of Grief

-

Published30 Sep 2020

-

Author

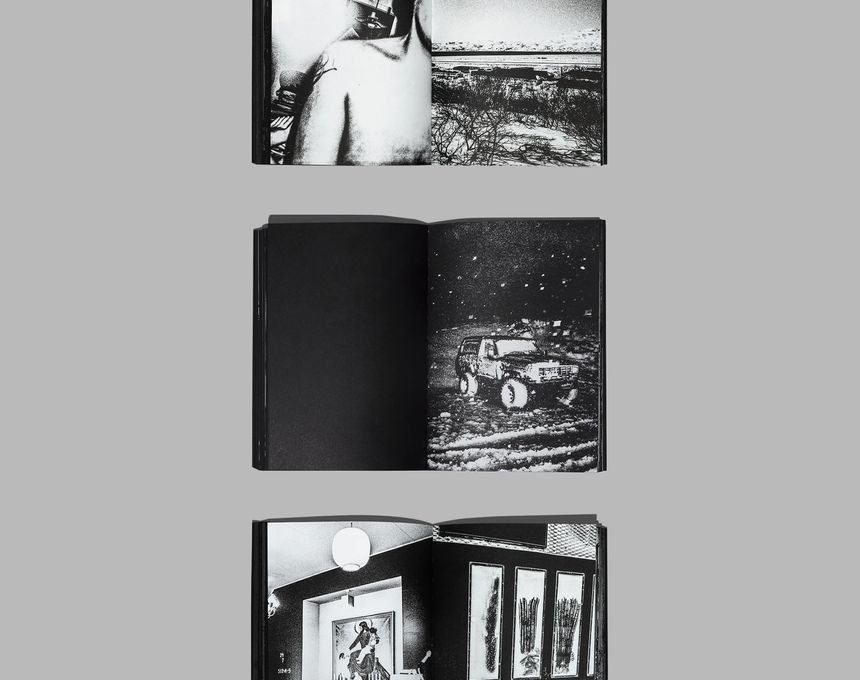

Venezuelan photographer Fabiola Ferrero has long been photographing the collapse of her homeland: street protests, health crises, and political unrest. For her latest project, I Can’t Hear the Birds, she looks back to her earliest memories of the country through a collection of old family photo albums.

Venezuelan photographer Fabiola Ferrero has long been photographing the collapse of her homeland: street protests, health crises, and political unrest. For her latest project, I Can’t Hear the Birds, she looks back to her earliest memories of the country through a collection of old family photo albums.

Fabiola Ferrero describes how every year after summer friends would bring photos from their holidays. Somewhat one of her earliest memories. However, as a result of Venezuela’s migration many of those family albums have piled up in empty homes. Fabiola, moved by Venezuela’s exodus, decides to mix-up images from old family albums with her current photographs of Venezuela in order to raise questions between the past and the present.

Fabiola describes her series I Can’t Hear The Birds as an emotional journey of the grief caused by migration, but from the point of view of the person who stayed behind and watched all the change.

Fabiola, could you tell us more about the title of your series, I Can’t Hear the Birds, and how it came about?

Eugenio Montejo is one of my favourite Venezuelan poets. He wrote a poem called “Debo estar lejos” (I must be far away). And it goes:

I must be far away

because I don't hear the birds.

I have lost the afternoon in its emptiness,

I have toured this city

of foreign voices

only to realise how much I rely

on their songs,

and how their whistles drop by drop

are mixed in my blood.

I must be far away

or the birds have become silent

intentionally

for their silence to return to me

and my steps walk back the stones

of this long street

until I hear them again in the wind

and the migrant heart become numb

under their wings.

To me, these words describe perfectly the migratory grief, the sense of being taken away from your familiar places, sounds, and smells. And in Venezuela’s case, this feeling of loss/mourn applies even if you stay in the country, because the home where we grew up no longer exists, it is something else, something still a bit unclear.

I Can’t Hear the Birds is an emotional journey, not just about Venezuela but about the human experience of loss, and in this mixed narrative we constantly move from the glimpses of our memories and a dreamy state to waking up to the reality of abandonment.

You’ve been working in Venezuela as well as in Colombia for a few years now. How has working between borders influenced your perspective of your homeland?

It helps you build a wider perspective. It reminds you that every country has a rich story to tell, and that most of them have also had their share of suffering. Colombia has a very violent history, and you can see the scars nowadays, we as Venezuelans used to receive Colombian citizens running away from conflict and now, they are the ones receiving us.

It helps me remember the everlasting change and that we can also document happiness and better times. Same happened last year, I took a 3-month trip across South America and it was a strong reminder to get out of my own head and be aware of the richness of everyone’s backgrounds, because although my country will always be the most important story for me, working in the rest of the continent makes me respect the variety of topics and stories you find here, and they are all valuable.

How have you found your personal process of understanding what Venezuela is and what has it been like to translate it into photographs?

Working as a journalist is about staying out of the story, and when I work for media or do straight documentary works, I respect that.

In this case, I am giving myself the freedom to talk about my family too, and I think it makes the project more honest. Out of five members of my family, I am the only one left in the country (although during the pandemic I have been away).

At times, it feels wrong to do this type of story : in the middle of the turmoil I know that so many people are leaving because they don’t have enough to eat, but over time I have come to terms with the value of these stories too: the Venezuelan middle class, those who don’t leave because they don’t have food, but because they want a different life. There is grief there too and translating it into images has shown me once more the power of art to understand our emotions, and to respect the timing of those processes, not to rush it.

Are you only using your family photo album archives or are you also including photo collections from other families?

There are collaborators in this project, and they can write a diary, intervene images or draw, anything they want to express themselves. Some of that material is also part of the project. There are images from their family albums, their empty homes, some portraits of their family members who are still in Venezuela…

My story is just one more in the narrative, not the center. The aim is to work with our grief constantly and in many ways, it is more about helping others, and myself, to codify this new sense of loss we were forced to deal with. One of the collaborators, who said writing about her experience helped her own healing process, wrote one of the most beautiful phrases I have read so far about our migration: “I am starting to forget how my mother’s hair smells like”. In a few words, she gave a poetic meaning to her - and our - pain.

How are you using the family photo, meaning, are you altering/editing them in any way or are you keeping it as it is found?

Some images are so strong that I didn’t touch them, like the one with the kid looking at the guacamayas dressed as a devil, that is from my friend Nolan’s album. Others are slightly intervened, like the one with my brothers at the beach with sand on it, or one I took out of focus so you could only see the shapes, or one that is covered by the spider paper.

Others are projected in the walls of the empty homes, as a way to give another meaning to that space, to give the memory one more chance to inhabit those houses.

This is a long process and it has allowed me to play with the different elements, the final selection will surely leave out a lot of it, but the process itself IS the project: how grief changes its forms over time also influences how the images are produced. Looking back will be interesting, because something that was painful at one point might have changed by the end of it, and that is the whole point.

In this series, are you including images produced during the protests as well? Can you tell us more about your framework for this series?

Yes. In the end, all my work is becoming one big project about Venezuela’s collapse and how we, as a society, are grieving the loss of what we once knew. The violence and political turmoil are one chapter of it, and I Can’t Hear the Birds is another one, and they constantly mix. Hopefully there will be a third when things stabilise.

But the question has always been the same: How is this crisis affecting our souls? How is it changing us as individuals and as a society? Not necessarily as a lament or a complaint, but just as a way to become witnesses of our own pain, and work with it instead of denying it.

-------------

Fabiola Ferrero is a photographer based between Venezuela and Colombia. She is part of the World Press Photo 6x6 Talent Program South America, the VII Mentor Program and a Magnum Foundation Fellow. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

-------------

This article is part of In Focus: Latin American Female Photographers, a monthly series curated by Verónica Sanchis Bencomo focusing on the works of female visual storytellers working and living in Latin America.