Smuggling a New Life From Behind the Bars

-

Published7 Jun 2017

-

Author

Antonio Faccilongo chronicles the smuggling of sperm from Israeli prisons, allowing detainees' wives to undergo in vitro fertilisation.

Antonio Faccilongo chronicles the smuggling of sperm from Israeli prisons, allowing detainees' wives to undergo in vitro fertilisation.

The lives of Palestinian women whose husbands have been convicted are suspended, then, a spark of life, both figurative and literal, returns. More than 6,000 Palestinian men are detained in Israeli jails, according to statistics compiled by the Addameer Palestinian prisoner association, the Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem, and reported by various news outlets. Some of the prisoners have been convicted while others were taken into custody as a “security measure” due to Israeli military fears that they could present a threat. Most of the arrests were carried out in Palestinian refugee camps.

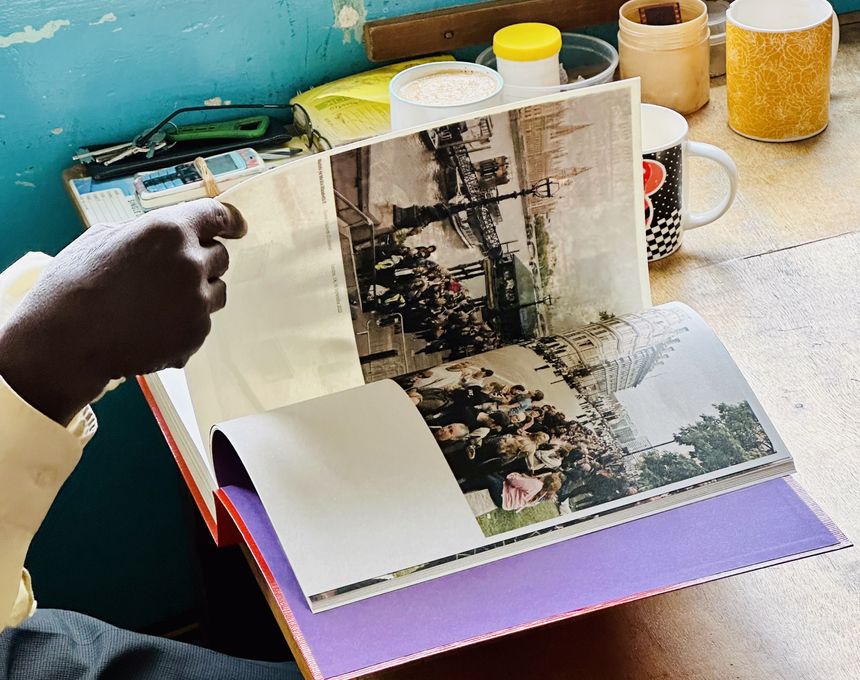

Struck by the impact of the high number of male detainees on families, Italian photographer Antonio Faccilongo chronicled the daily life in Palestinian refugee camps in his work (Single) Women. Then in 2013, he started focusing on the phenomenon of sperm smuggling, as inmates began providing their wives with semen from behind bars to undergo in vitro fertilisation (IVF). The result is the photo reportage Habibi, which granted Faccilongo the PHM 2017 Grant 2nd Prize.

Marital encounters are forbidden in Israeli jails, and prisoners are only allowed to have physical contact with their children - aged 6 or younger - for ten minutes at the end of each visit, every two weeks. During those encounters, the inmates give their children little gifts - mostly candies or chocolate bars - which present an opportunity for the transition of semen.

Semen is often stored in plastic ballpoint pen cases, wrapped in a chocolate snack paper. When they leave the penitentiary, gift in hands, children and wives turn it over to two members of each spouse’s family, to ensure that the sample belongs to the husband. At the clinic, IVF is performed free of charge, a tribute to the service wives and husbands have given to their homeland.

Now more tolerated, the practice was at first curbed by solitary confinement. The Atlantic reported that in 2013, the Palestinian Supreme Fatwa Council established new conditions, limiting the practice to men who serve long sentences, marriages consumed before conviction, or when any other way of pregnancy is ruled out. At least 40 babies have been conceived through IVF from smuggled sperm.

It’s a lengthy, at time discouraging, bureaucracy that led Faccilongo to meet the women he photographed. Palestinian Prisoners Club - an NGO that supports political prisoners in Israeli jails - provided their contacts, but permission follows a precise hierarchy: granted first by the incarcerated husband, then by his family, the wife’s family, and last the wife. “The problem was that I was asking these women, who were alone and on their own, and who didn’t know me or either did any of their family members, to have an interaction with me and to do so in daily life situations - that was the most crucial point,” Faccilongo recalls.

Most of the encounters took place in the formal setting of their living room, diminishing the possibility of an intimate connection: “I could meet the woman only in that room, and that was it. There was no occasion to deepen and explore the interaction, even from a photographic point of view,” Faccilongo says. “Patiently, I had to make them accept me, slowly wait for them to trust me.” Once the trust was established, often befriending male family members first, Faccilongo could spend more time photographing the women in their daily life, following them to the doctor, the playground, or the grocery store.

Depicting fragmented and emotionally charged settings, Habibi - the Arabic word for love - reflects a kaleidoscopic view: suspended, at times unrealistic, moments of waiting; the presence of a husband denied and then retrieved by the wife through the use of a smartphone; and the women's sense of resignation fading in the midst of the bustling activities at the clinics. Ultimately, the series celebrates life: for the women, who reclaim their femininity, tattered by their husbands' absence; for the men, whose offspring grow despite their confinement; and for the children, discovering the meaning of family and the future. Habibi is a celebration beyond the atrocities of war.

--------------

Antonio Faccilongo is an Italian documentary photographer. His work covers social, political, and cultural issues in Asia and the Middle East, principally Israel and Palestine.

Lucia De Stefani is a multimedia reporter focusing on photography, illustration, culture, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.