Reviewing the History of Belgian Photobooks

-

Published21 May 2019

-

Author

What is photography for? It’s to serve power, to uphold elites, to divide and conquer, to lie and deceive. What’s photography for? It’s to question power, to critique elites, to unite and be truthful.

What is photography for? It’s to serve power, to uphold elites, to divide and conquer, to lie and deceive. What’s photography for? It’s to question power, to critique elites, to unite and be truthful.

Photobook Belge (1854 – Now) is the latest in a rash of photobooks that have been published in recent years. The rash started in 1999 with Fotografía Pública, gathered momentum in 2004 with Parr and Badger’s Photobook History Volume 1, and has continued apace since then. There have been Latin American, Spanish, Dutch, Soviet, Japanese and Chinese photobook collections and that is just scratching the surface. The joke goes that it’s only a matter of time before the first History of History of Photobooks photobook is published.

Photobook Belge is a valuable addition to the ongoing literature on photobooks. In chapters that range from the contemporary photobook back to the 19th-century, it reveals something of the way of thinking that makes Belgian photography so interesting.

To date, most photobook histories have followed a very similar model. The difference comes in the chapter layout, the key themes and how they connect to national or political identities, and photographic history. The Dutch version has chapters on landscape and youth cultures reflecting both contemporary and historical obsessions, the Latin American version has chapters on ‘forgotten ones’ and ‘image as text’ reflecting a history of revolution.

The chapters in Photobook Belge have sections on 19th-century photography, The Congo, Word/Image, Belgitude, The World seen from Belgium, and Artist’s books. It’s a serious book with a serious voice then, but one where there is a merging of the photographic with the historical, a feeling for why images were made and how they reflect a nation that is divided by language, class, and geography, but still manages to retain a defined sense of identity (however split it might be) despite having France, Germany, and the Netherlands as neighbours.

The first chapters start with a customary look at the medical, scientific, and commercial uses of photography before moving into neue sachlichkeit, the destruction of World War II and the postwar rise of specifically Belgian concerns such as the Flemish language movement. It’s customary photobook history content fare but at the same time there is a constant reminder in this volume of the functions of photography, of the power that it serves.

That idea of photography and power is especially apparent in the Congo section. Congo was used as the private rubber producing slave nation by the King, its horrors visually shown by Alice Seeley Harris in what was possibly the first campaigning use of photography to expose human rights abuses with what the text calls "atrocity photography."

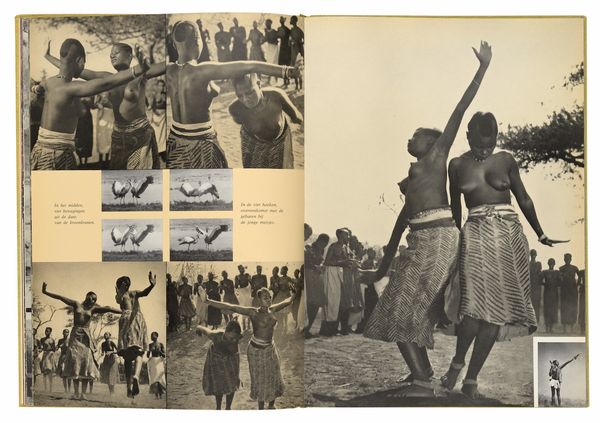

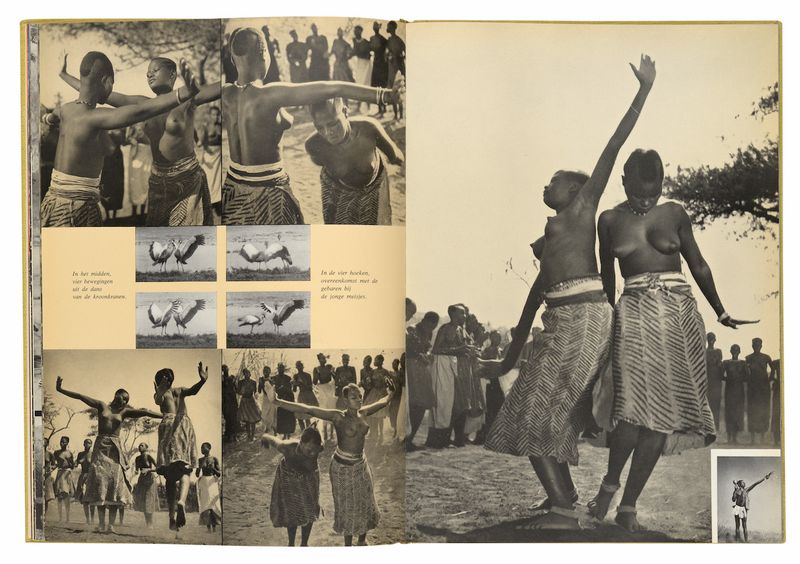

There are none of Seeley Harris’ "atrocity" images in Photobook Belge, but the chapter does show how photography was used as a form of propaganda and control in the Congo Free State and beyond. "Each of the so-called ‘three pillars’ of the Belgian colonial enterprise – the state, the church, and the capitalist companies – were photographic producers that sought to foment the colonial spirit," the text reads. So, there were photobooks showing the "pride" of tiny Belgium "owning" such a large region. Photobooks show the tribes, flora and fauna and the development that Belgium was supposedly bringing.

The text describes books that show Europeans dwarfed by the scale of things, by the immensity of Africa. It's a mirroring of American survey photography, its photography used to claim ownership. That ownership is reprised in representation of Congolese women, many of whom have their arms raised to reveal the erotic possibilities of their breasts. Here the language of the hunt and authenticity is used to describe how images are made and shown. Those pictures of bare-breasted women are not retouched as "…pledges to the ‘veracity’ of these photographs, but also spoke to the tangible availability of these ‘lascivious’ bodies…"

As the century progresses so the images change. There is a move away from the anthropological to the modern. But this is even more of a myth. Familie Album shows a mythical Belgian-Congolese community of a mixed middle-class community (though the black ‘middle class’ constituted just 12,000 people out of a population of 13 million). So you see a black man on the phone next to a white man on the phone, a black man posting a letter next to a white man posting a letter, a white woman sewing next to a black woman sewing.

Photobook Belge questions this post-independence view of Congo, lamenting that despite the inclusion of Leonard Pongo and Sammy Baloji, it’s still very much the white man’s gaze.

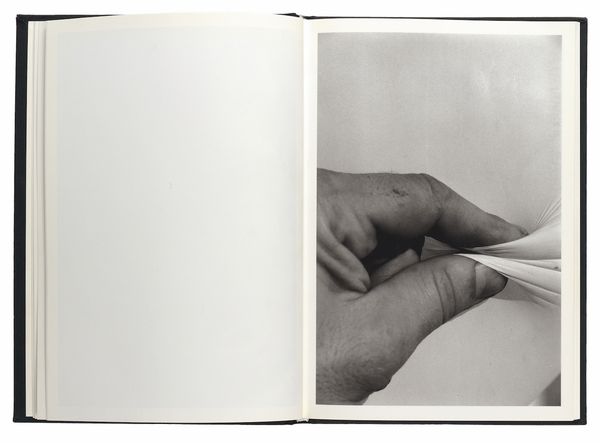

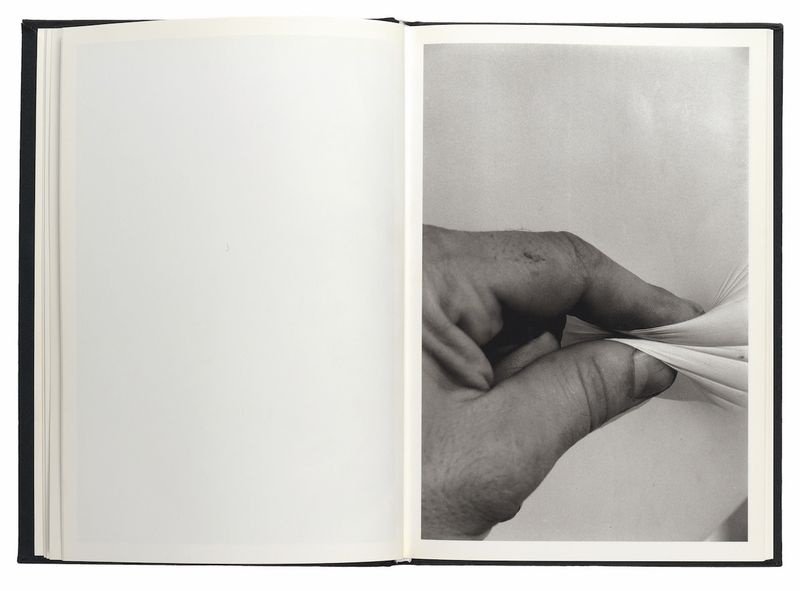

The image text section shows the narrative overlap between the photo novel, and poet image combinations. Here there is the idea of text working with the "time and space" of layout and the blurring of the lines between the poetic and documentary. It’s a blurring that is something of a theme in the book and is wonderfully seen in Droit de Regards by Marie-Françoise Plissart – a photo-novel where stories of love, the look, and language overlap.

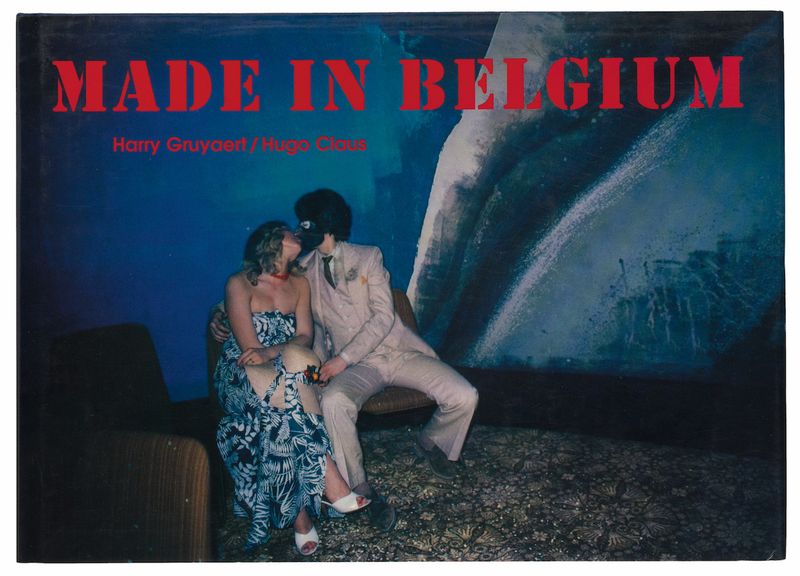

The final section is the contemporary Belgian photobook and it is here where the Belgicity comes through with a text that looks at the rise of the independent publishers like Art Paper Editions and Le Caillou Bleu as well as self-publishers like Max Pinckers and Vincent Delbrouck.

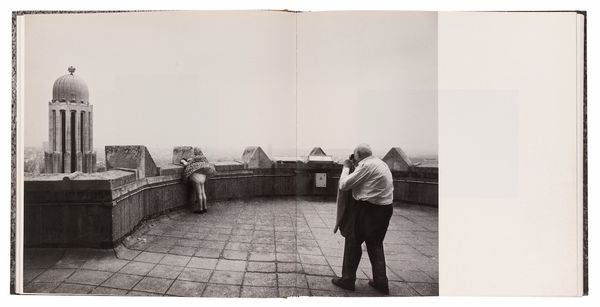

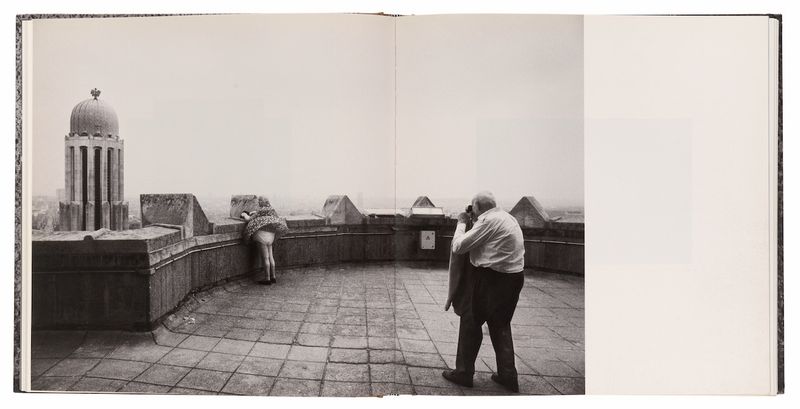

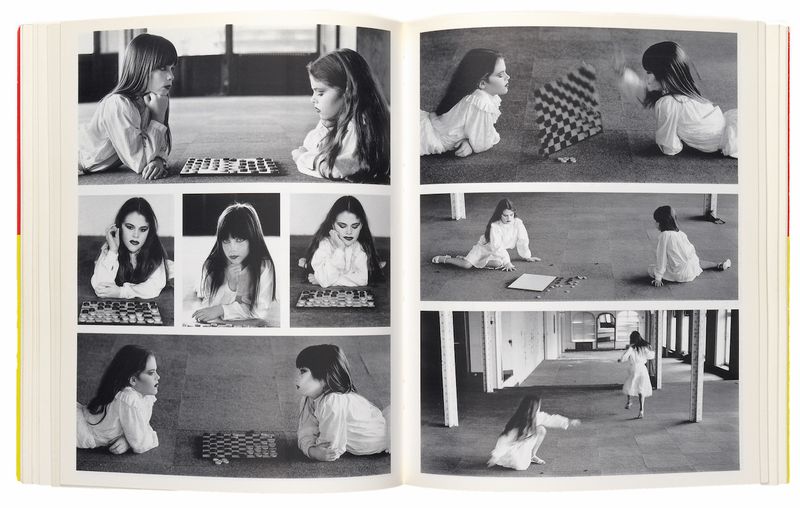

Again, the cracks between photography, reality and ways of showing and seeing come through in the weirdness of Dirk Braeckman’s z.Z(t), a grey-scale homage to crime scene photography and the haunted house, or the Bollywood inspired escapism of The Fourth Wall by Max Pinckers, where smoke bombs and holes in walls transform Mumbai into a 1970s movie set.

Then there’s the personal directness of Anne de Gelas’ L’Amoureuse and Sandrine Lopez’s Moshe, books where grief and bathing find expression through the affective qualities of the body.

Photobook Belge is a serious volume with writing that illuminates the history and idea of what being Belgian means. It’s a book that questions photography, that critiques how photography has been used and how it can be used; a reflection both of the skeptical hard-nosed anti-establishment idea of the country, and of the socially engaged photography that cuts against the grain in more ways than one.

--------------

Photobook Belge 1854 - Now

Published by FOMU in partnership with Hannibal

Hardcover // 352 pages, illustrated, // 29.2 x 24.5 cm // English // €59

--------------

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest book, All Quiet on the Home Front, focuses on family, fatherhood and the landscape. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.