Rehab Eldalil’s Collaborative Celebration Of A Bedouin Community In Southern Sinai

-

Published9 Mar 2023

-

Author

- Topics Documentary, Photobooks

Interview with Rehab Eldalil about her collaboration with a Bedouin community in South Sinai

Freshly published as a book through the FotoEvidence W Award, The Longing Of The Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken is a profound manifesto on identity, land, and on the way the two can’t be without one another. It is a layered exploration of what belonging can mean for a highly discriminated community, and for an individual whose roots are unclear. In conversation with Rehab Eldalil, a gentle and empowering perspective on collaboration emerges, expressing the right - and urge - to tell collective stories as a way to actively fight oppression.

Rehab Eldalil’s connection with the Jebeleya tribe started fifteen years ago, as she engaged in the creation of a volunteer-based community clinic providing free medical services in St. Catherine. This ongoing practice as a civil rights activist and her photographic work are rooted in the same visceral need: that of engaging for the empowerment of the marginalized Bedouin community, which continuously struggles with the Egyptian authorities.

The identity celebration we find in Eldalil's book comes from her perpetual search for the right distance. One that would allow for stories to powerfully emerge, while giving her photographic perspective space to breathe, one that would provide a platform for political claims to be carried through, while subtly reflecting on the complicated discovery of the photographer's own Bedouin ancestry. The resulting work is an ode to belonging, an archive - as Eldalil herself calls it - that points to the importance of knowing who we are, and to the beauty of doing so with others.

I’m really interested in the collaborative aspect of your work. How is this story a collective one, and how did the exchange between community members and you practically take place?

As I was not brought up as a Bedou, I felt like I couldn’t tell the story myself - my voice alone wouldn’t feel right. Even with the huge connection between us, I’m the stranger. As the work evolved into a community project, this aspect was sort of liberated.

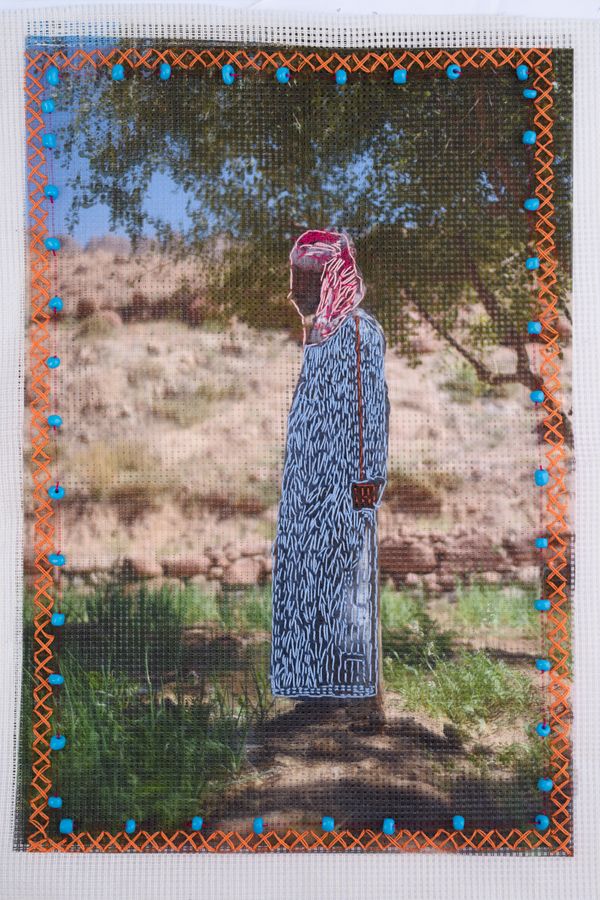

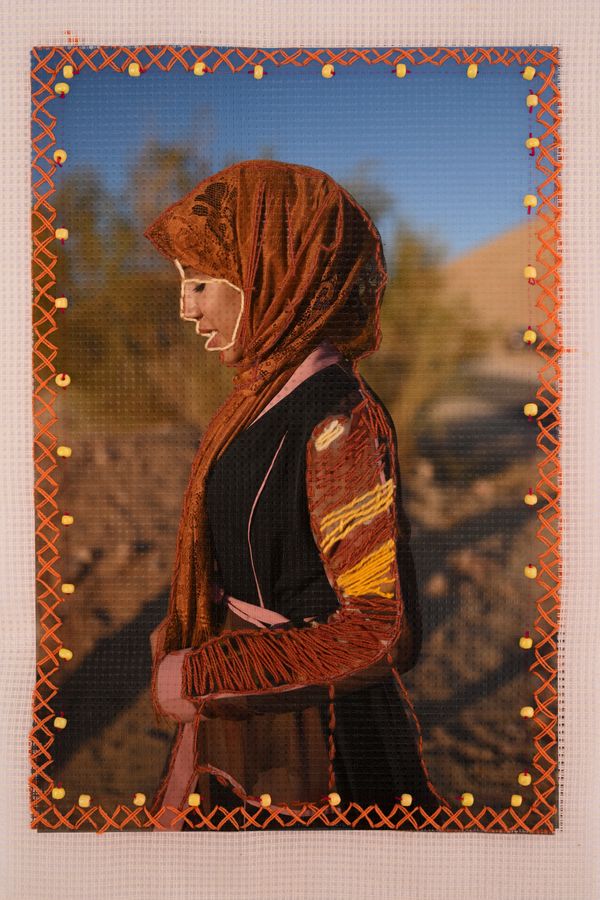

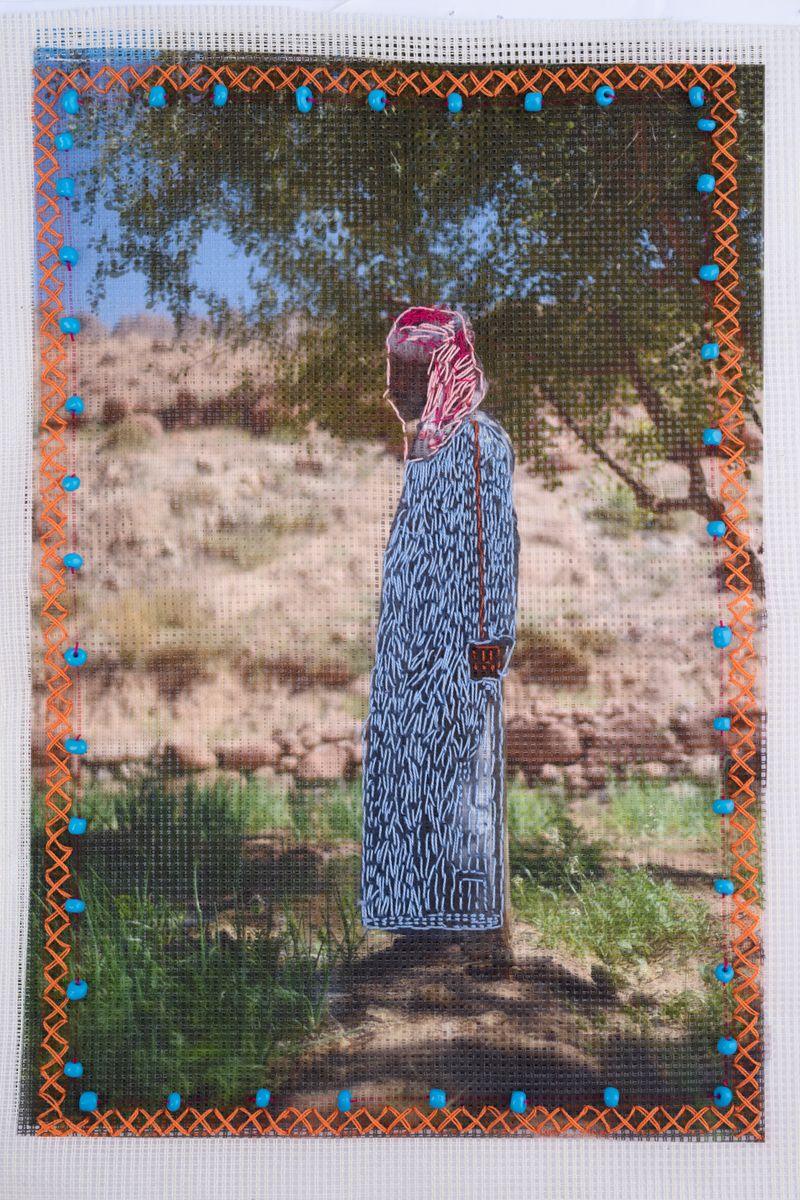

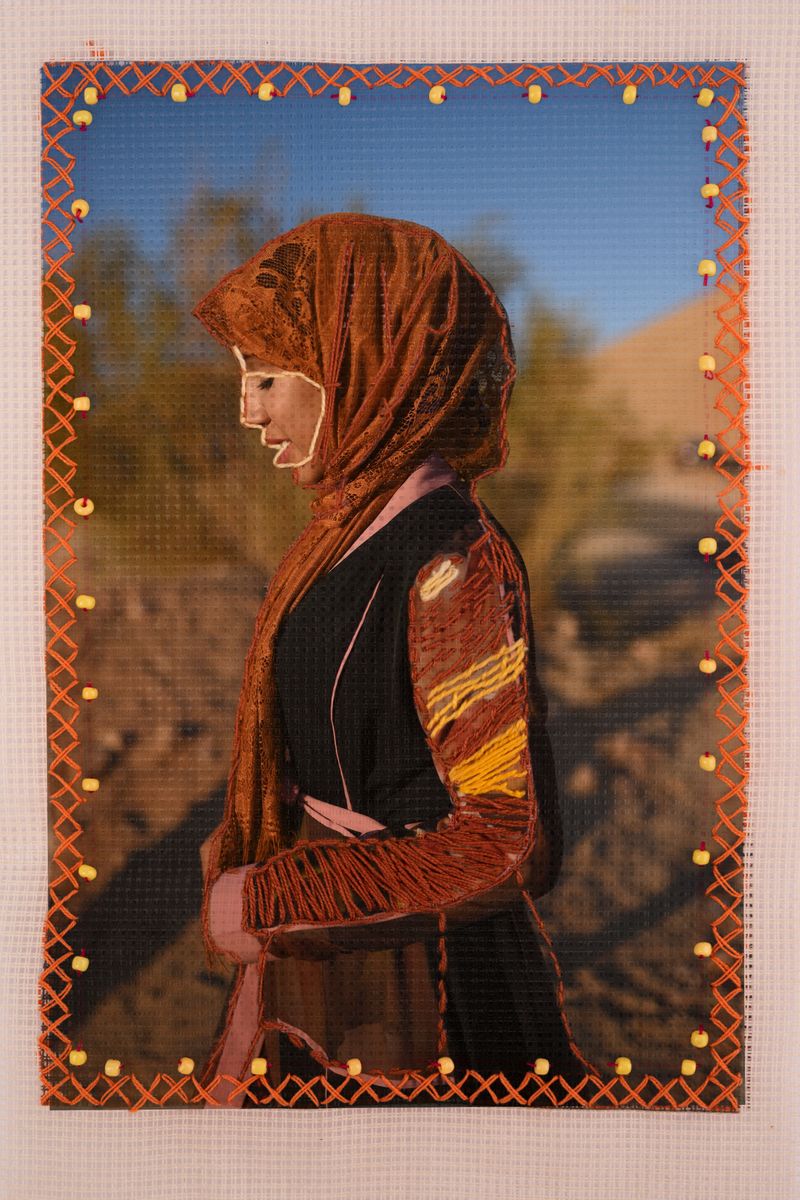

It first started with the women in the community. Including their voices came with a lot of obstacles, as they were very concerned about the way their images could be seen from the outside, and taken out of context. The image, or the trope, of the Bedouin woman is this very delicate, shy, voiceless being. They are, actually, the main pillars of the community - the ones who work every day to provide for the family, statistically more educated than men. I invited them to bring their own traditional medium, which was embroidery. Using it over textile prints, they could have full control over what was shown, and what was hidden. It was all very empowering, as their use of the technique then developed beyond the portraits and started being used as a more comprehensive commentary they gave on their families, and land.

The next step was to include men, and the best medium to do so was poetry. Bedouin villages address each other using poetry, love is talked through poems posted on Facebook, and the same goes with frustrations towards the government, as it’s a subtle language that they would not understand, nor target. A lot of images in the work give explicit context on the political situation, helping to read the poetry through the lens of power struggles, of this love-and-hate relationship of cherishing a land, but suffering the stereotypes that come precisely with this belonging.

The photos of plants are, then, the third collaboration. The older members of the community would talk about how the land is there to define and protect them. How they are the keepers of it, and how it always saves them. One of them started to forage plants as proof of this bond, and a field guide was eventually born out of this. It is meant as a bridge between older and younger members of the community, other than as a celebration of the flora.

Did the moment of embroidery also work as a way of making interesting conversations emerge?

They took place after, as the women would bring the embroidered pieces back to me. Initially, they were using embroidery as a way of obscuring. But when I saw Nadia’s portrait, the first in the book, I noticed she was instead accentuating her profile. She told me it was not the time for hiding anymore - she wanted to have control, to celebrate herself. This ignited a discussion on representation and agency. Another piece shows Hajja in a garden. Her daughter embroidered birds, a dog, and foxes all around her. We started talking about climate change, and its impact on the landscape: even though Sinai is considered a desert, it used to flood every year, allowing for the gardens’ richness in flora and fauna. Hajja told me how much she missed the way her garden used to flourish - something her youngest son, who is ten years old, sadly never saw.

Collaboration allows for guidance, but never for total control over one’s work. How did this balance work out?

As ownership is shared with other people, you become very vulnerable. This was a bit of a struggle as I started to photograph the community. They were very self-conscious of their image’s outside perception and would, for example, ask me to be portrayed holding a cell phone, to make sure they’d show that they have a network connection, and that they are modern. I, of course, took the photographs - but knowing them quite well, I could see the additional layers. There are ways to revolt against the idea of indigenous people being closed-off, while still maintaining their identity. Ways to go beyond this manipulation of modernity that sees being western, and urban, as the way to show you’re not excluded, uneducated, or whatever. I needed to have patience: after I took these photographs I would take more, and different ones, until they sort of let go of this consciousness of the images’ reading. They had their input, and I had my own. It’s something that needs discussion, patience, and trust. This was necessary in order to create actual, real stories.

How did they react to this whole process, and to the final result?

I was always scared - what if I am only exploiting them? What if they’re collaborating only because of the clinic I’m providing? But their excitement would keep me going. They kept wanting to participate and said it gave them a platform to express their voices. A very emotional moment happened during the book launch in Cairo, two weeks ago. Moussa, the person I portrayed with the flower in his mouth, joined me on stage. As I asked him what he thought of the book, he answered that he had always wanted to do something for his community, something to celebrate his identity, but he couldn’t articulate it. I was able to do it for him, he said. This is the validation that I wanted: making sure that the community feels they’ve been able to celebrate themselves. That I was able to honour them.

There is a story of community celebration and identity expression - but then, there’s also your own personal bond with it. Can you tell us more about this personal journey you went through?

I wasn’t able to track down the exact roots of my family, as details about our Bedouin ancestry were hard to find. For a very long time, I really felt like I needed them, as to sort of prove my legitimacy over this project. But I then found out that making peace with the fact that I’m a stranger, hence the title, was really important. It's what actually helped me to push towards a more collaborative manner of telling the story. The reconnection with the land allowed me to still find a sense of belonging, without needing to know more about my family. Creating this alternative archive of the Bedouin community, by the Bedouin community, has given me peace with the fact I wasn’t able to find my own. I now have this sort of closure: I feel like I have honoured my Bedouin ancestors I don’t know much about, by honouring the Bedouin community that is here today.

--------------

All photos © Rehab Eldalil, The Longing Of The Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken

--------------

Rehab Eldalil (b.1989) is a documentary photographer and visual storyteller currently based in Cairo, Egypt. Her practice focuses on the broad theme of identity explored through participatory creative practices. Her work was shortlisted for PHmuseum Women Grant 2021, and 6Mois Photojournalism award 2021 among others. Most recently, Rehab was awarded the Foto Evidence W Award 2022, she has won the World Press Photo Regional Award 2022, and was awarded the Premi Mediterrani Albert Camus 2022.

--------------

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based between Italy and The Netherlands. Holding a BA in Graphic Design from ISIA Urbino (IT), she is about to graduate from Design Academy Eindhoven's MA in Information Design (NL). Her work, often realized in a duo with Gabriele Chiapparini, was exhibited in several festivals and galleries including Fotografia Europea, Kranj Photo Fest, and PhMuseum Lab.