Questioning Judaism as a Young Mexican Woman

-

Published21 Jan 2021

-

Author

Motivated by her inherited religion – Judaism – Mexican photographer Orly Morgenstern looks to question her practice and the social expectation that is framed within it. While in quarantine, Orly photographed the domestic corners of her house; objects, old photographs, and texts to raise her personal concerns about the religion.

Motivated by her inherited religion – Judaism – Mexican photographer Orly Morgenstern looks to question her practice and the social expectation that is framed within it. While in quarantine, Orly photographed the domestic corners of her house; objects, old photographs, and texts to raise her personal concerns about the religion.

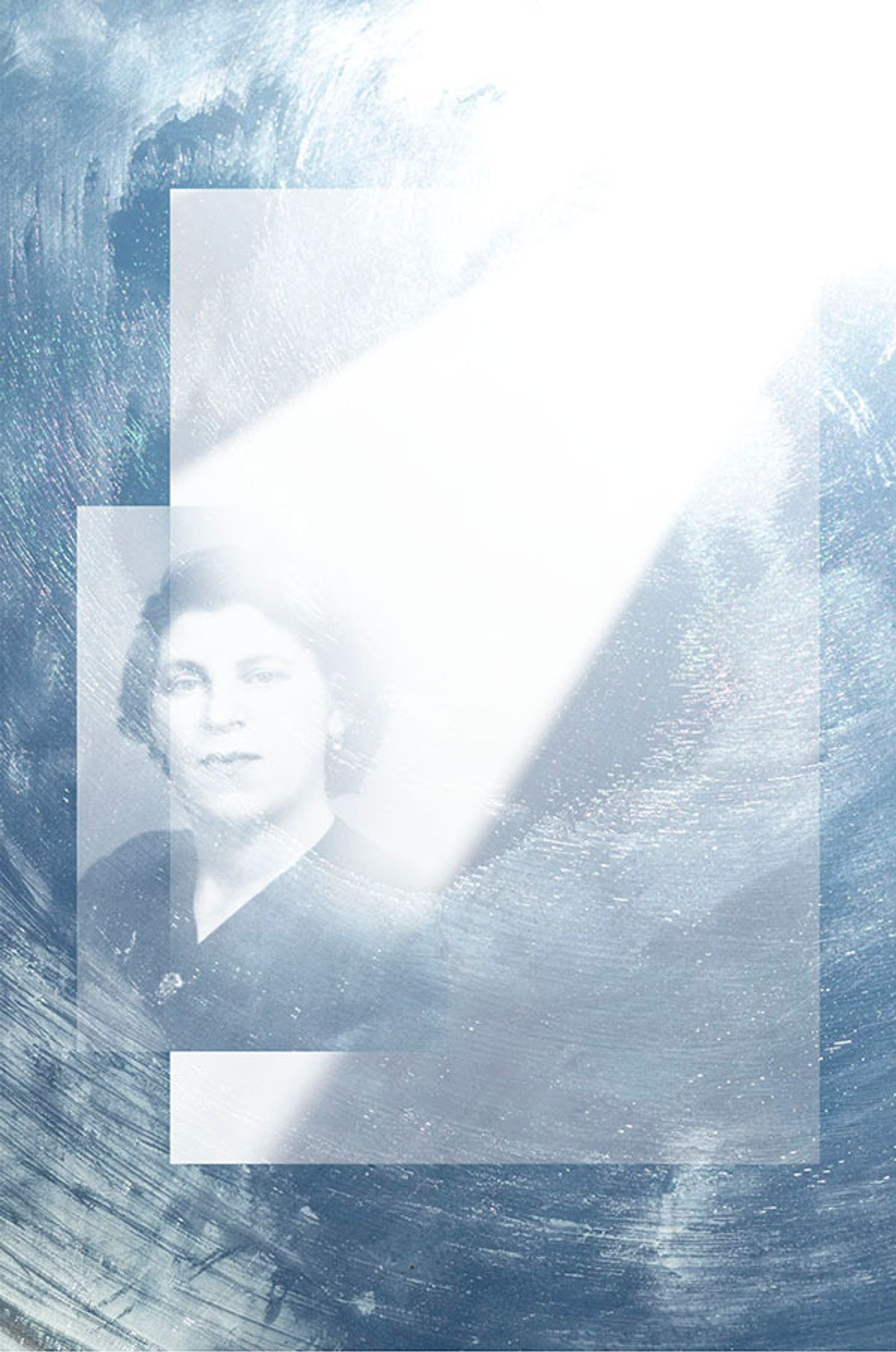

Yehudia is an ongoing series by Mexican photographer Orly Morgenstern. The personal project began during the pandemic in her native country and looks to question the meaning of Judaism as a woman today. Orly incorporates personal belongings in the form of photo album photographs, text, and objects in order to represent her family history as well as religious traditions. The series represents a labyrinth of emotions that Orly has felt since childhood which she is now channeling through photography.

Orly, let's begin by asking you about your project's title, Yehudia. What does it mean and why did you choose it?

Yehudia is the word for female Jew or Jewish in Hebrew, the word for Jew is Yehudi, so for the feminine pronoun you have to use the ending ‘a’; depending on the word, termination might change but, in this case, to say; I’m Jewish - I would say; ani yehudia (ani meaning I). Aside from the grammatical part, it’s important to mention that there’s a whole story behind the word Yehudi. For instance, it comes from the Yehuda tribe, one of the twelve tribes in the Torah. The story goes way beyond that fact, and somehow, it makes me question the origin of the naming of the cultural manifestation we know as religion.

Yehudia is a straightforward title, but by using it I am trying to refer to Judaism from a female point of view. When titling the project was the only thing left, I could only think of that word because, in essence, the project is merely an essay and an exploration of my Judaism as a woman; it even seemed a little obvious to use that title. I also considered accompanying Yehudia with ‘Mexican for Jewish', thereby implying that my nationality is an important part of the project, but I haven’t decided on that yet.

In your statement you mentioned you first questioned your Judaism at a young age, but when did you begin to consciously work on this project?

Consciously, I began this project in the middle of last year (2020) - as my final project in photography school. We had to propose a final ‘thesis’ and I chose religion as the topic because, besides the quarantine factor that prevented me from photographing many things outside my own house, I felt in a strong place to actively question my religious practice and education.

In a way, the quarantine situation pushed me to photograph something developing in the inside of my home, my family, and myself. But looking in retrospect, the questioning of Judaism while growing up was, and still is, a path of growth and constant learning activity that somehow has led me into different levels of understanding. So, it’s a recent project; still ongoing but deeply rooted in a restlessness that originated in the past. Religion is a huge topic. Judaism, for me, has been a way of life and structure. Naturally, the moment to question gender roles, life, death, responsibility, and above all, family and heritage, arrived. But yes, I would say that the questioning has always been a company to my Jewish practice, but just now materialised into the possibility of imagery.

While the core of this project is religion, it seems to me that you are also looking to raise a question in regard to gender. Would you say that's the case?

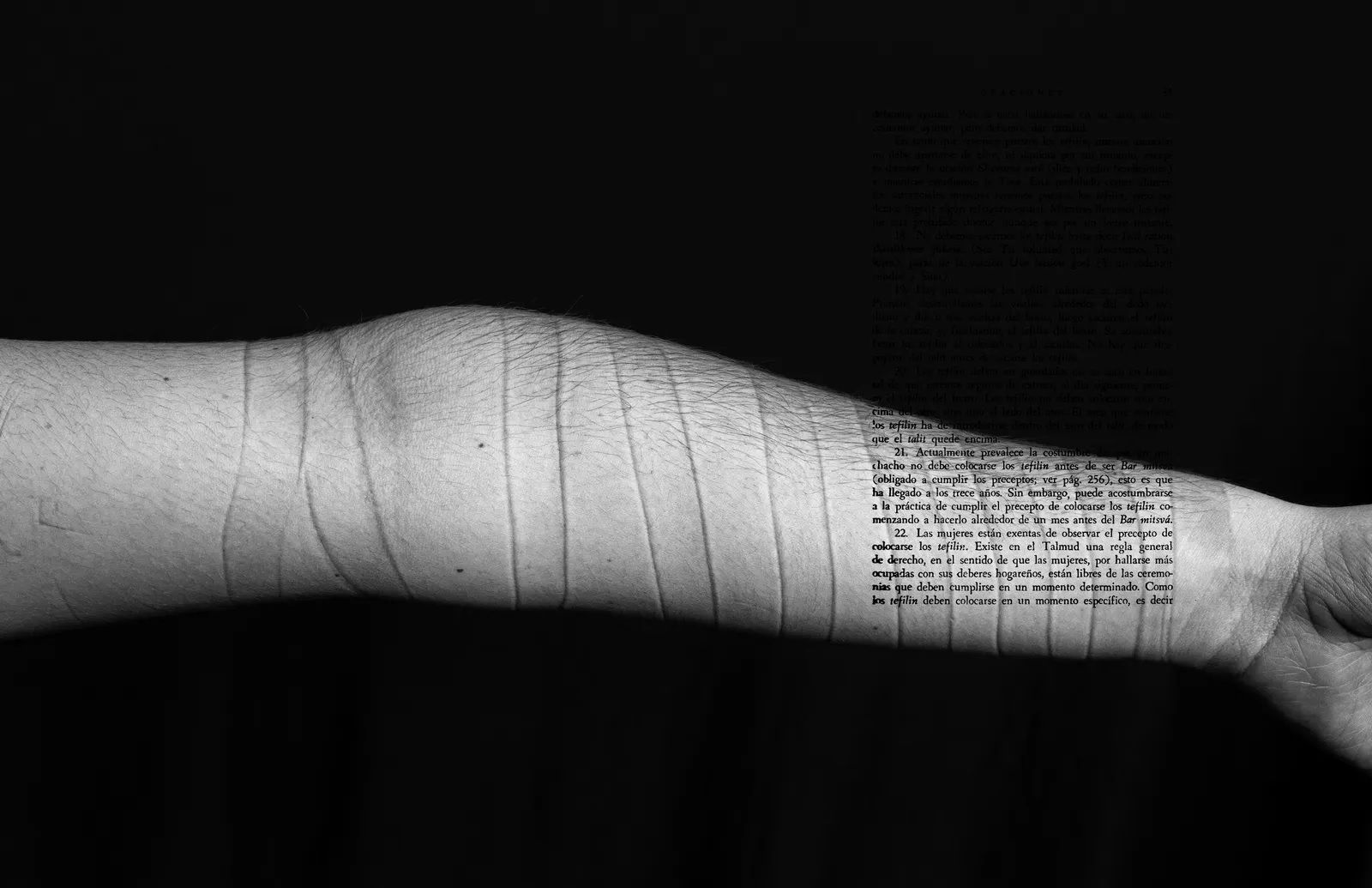

It’s completely the case. When I was building the line of the project, I concluded that my natural condition as a woman was going to be a definitive factor in the analysis and photographs to be made. I can’t differentiate my Jewish experience from my womanhood because it has been conditioned by it. In Judaism, gender roles play a huge part in the equation. I have two older brothers, both with very different rituals and responsibilities than mine, for instance; the bar mitzvah and the brit mila, both rituals exclusively for boys. One because of the anatomical constitution of gender, and another one due to societal factors that impose cultural responsibilities.

According to Judaism, women have different things to do and be; nevertheless, those particular rituals conducted by women have given me a window into the constitution of the female figure through a Jewish perspective. Many things are wise, others are still left to understand and, of course, some can always be criticised by cultural factors linked to specific historical times such as the feminist movement and others. Religion is a polemical topic but can only be understood by experience; my experience is as a woman.

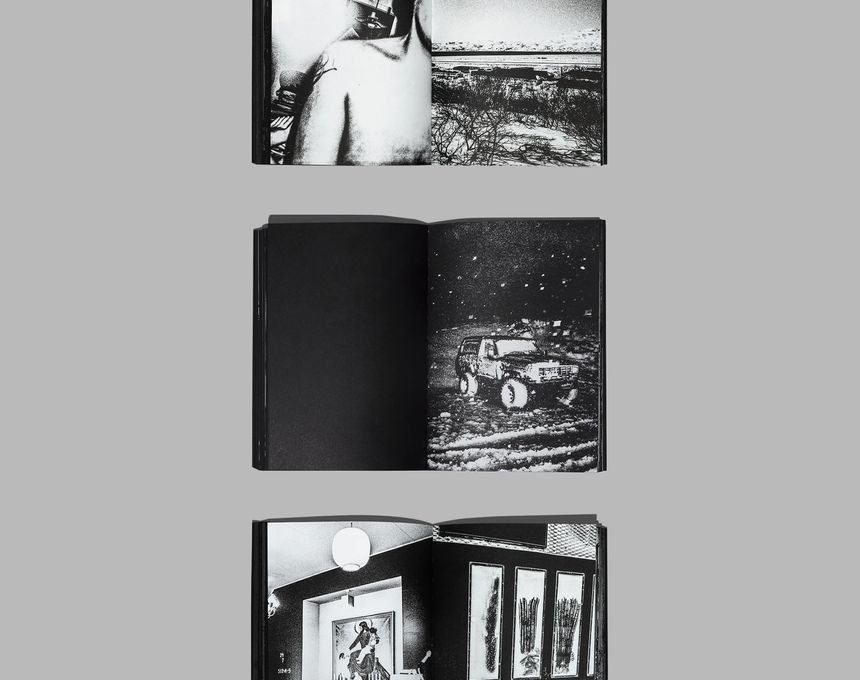

I would also like to talk about your image-making decisions. How did you decide to combine studio portraits as well as documentation and archival objects?

The main reasons are the restrictions regarding confinement. Due to the situation, I had to find different ways of making images with the resources I had at hand. Every new photograph made for this project was made from home. In the search for a visual dialogue regarding my whole experience as a Jew.

I referred myself to pictures taken on a trip to Poland, the homeland of my ancestors, and also to some archival photos from the 19th and 20th centuries in order to build a bigger and wider picture of my context. The use of these archival photos and objects was a tool to enable the conversation on the topic with its heritage. The family portraits were the window into my family history; it is where my Jewish origin lies, a definite line of the project, and a trigger for questions that helped me build many of the photographs.

While working with the subject of religion, what sort of reference may have influenced or inspired you while working on this project? Could you name or elaborate on their impact on your work?

The work of Adi Nes, an Israeli photographer that constantly reflects on masculinity and sacred texts such as the Bible, was a primary reference for this project in terms of subject and concept. I admire his composition, his sense of character, and colour. His work led me to question Jewish religious stories and biblical texts, but also, and most importantly, it led me to imagine different scenes or objects that could be represented through images.

Besides Nes, Nan Goldin’s project The ballad of sexual dependency. That has always been a relevant reference to me regarding the honesty needed behind a photograph. The photographic act, for me, must come from a true and honest place. Developing a project about an individual experience always requires empathy, authenticity, and truth, all of which must be visible through the images. All of those things stand out in Goldin’s work.

Also, Alec Soth’s work has always been a major influence on my perspective toward photography. Projects like Sleeping by the Mississippi are beautiful guides into the unknown territory that images can open to us. The constant conscience over colour and technique are some of the things I like turning to in his work and try to look for while doing mine.

-------------

Orly Morgenstern is a Mexican photographer currently based in Mexico City. Her personal work explores Judaism and womanhood. Follow her on Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

-------------

This article is part of In Focus: Latin American Female Photographers, a monthly series curated by Verónica Sanchis Bencomo focusing on the works of female visual storytellers working and living in Latin America.