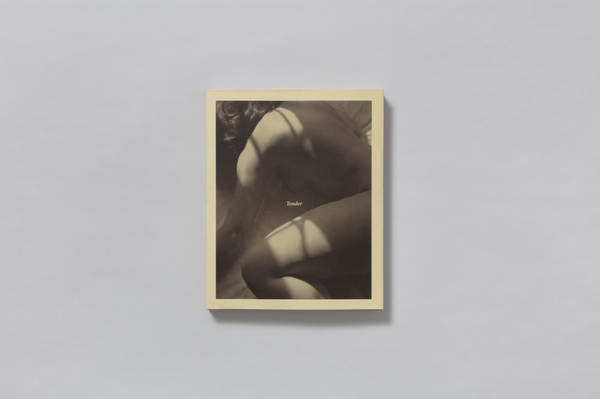

Photobook Review: Tender by Carla Williams

-

Published19 Oct 2023

-

Author

- Topics Photobooks

In TBW’s latest publication, the rediscovery of Carla Williams' archive of self-portraits is about the need to take pictures you've never seen before in your life. And about one belief: that nothing should ever bother us in a photograph of our body.

“Time is such a funny concept, isn’t it?” says Carla Williams as we speak on the phone. “Anyways, it just sort of collapses”.

One could tell the story behind Carla Williams’ photographs starting from many different points in time and space. The way she does so begins in a shop in New Orleans, right before Covid. The shop is called Material Life and it’s her own. Among the various, affordable art objects she collects and sells are some vintage photographs. Among the vintage photographs are some self-portraits she took a long time ago.

“My photographic work was completely out of my mind”, she says. “It had been set aside for years. I had made photographs intermittedly, just on my own, from 1984 up until about 2009. I did so very sporadically: I did not pursue an art career - and no one seemed to be ever really interested in my work, which in college was perceived as vain”. A customer of Material Life is a photographer, and gets to show the work to TBW’s publisher Paul Schiek. “It was really out of the blue, and it was such a surprising and such a fun thing because, who doesn’t like books? Paul was so lovely, I just instantly said yes, it seemed just a fun thing to do at this point in my life”.

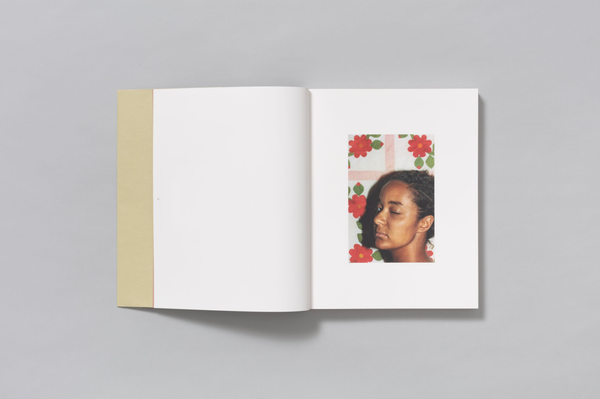

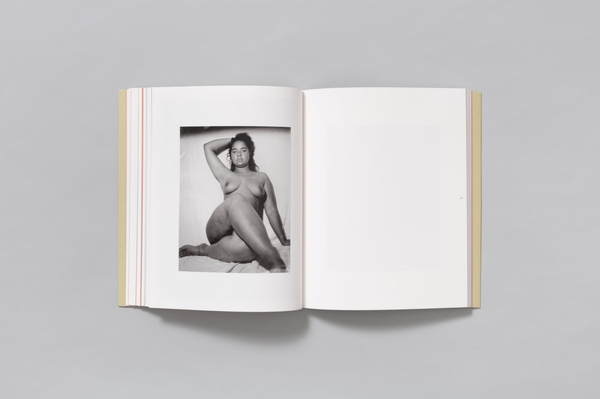

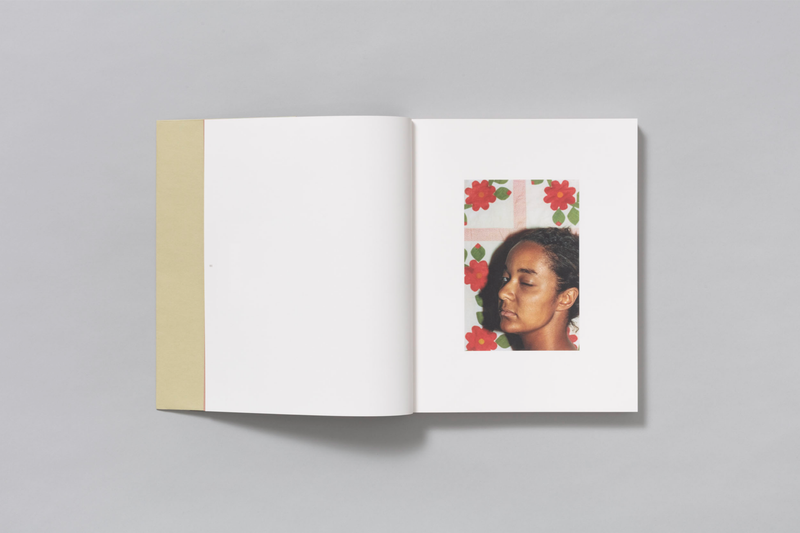

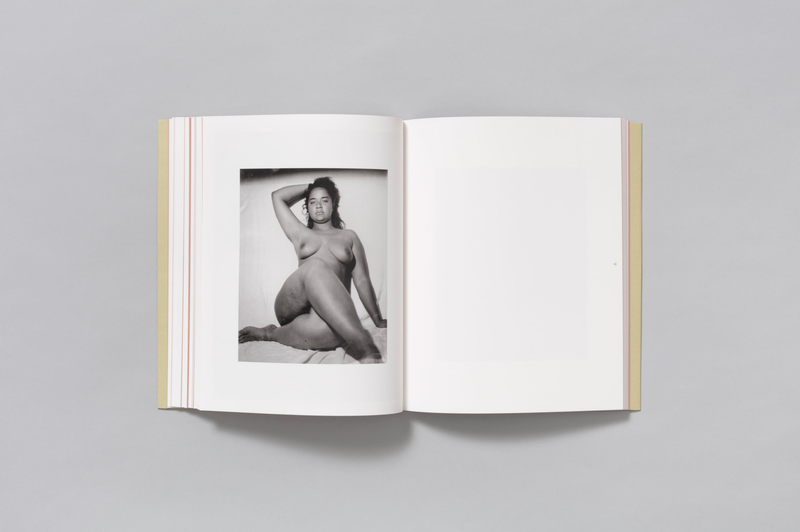

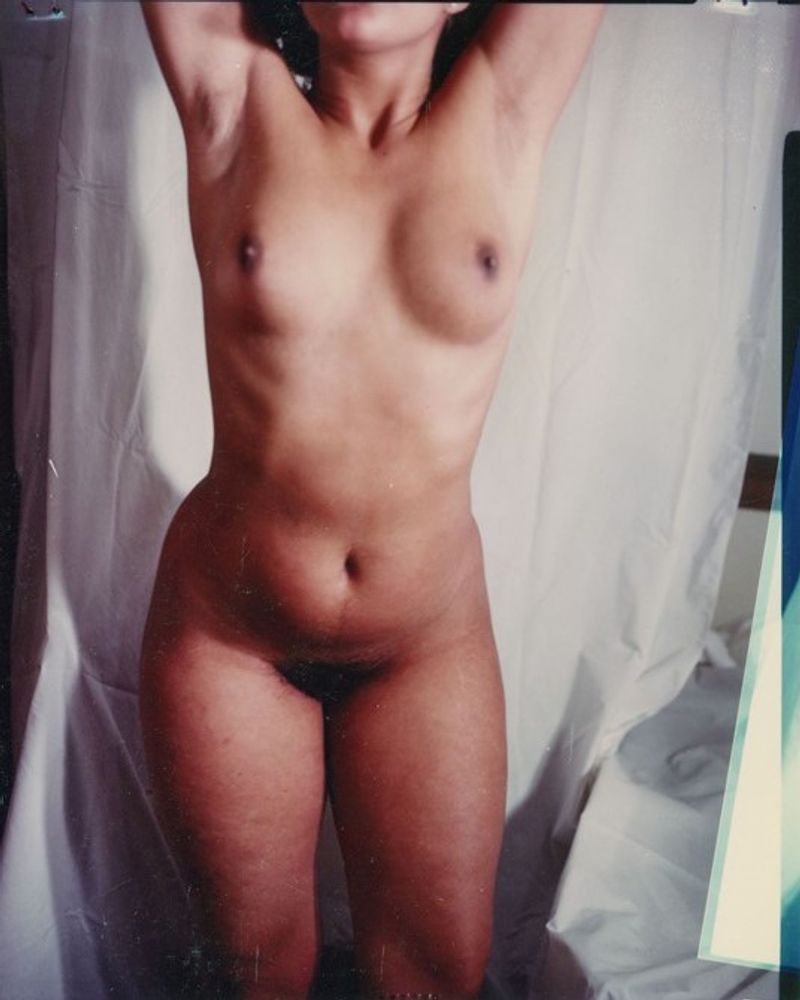

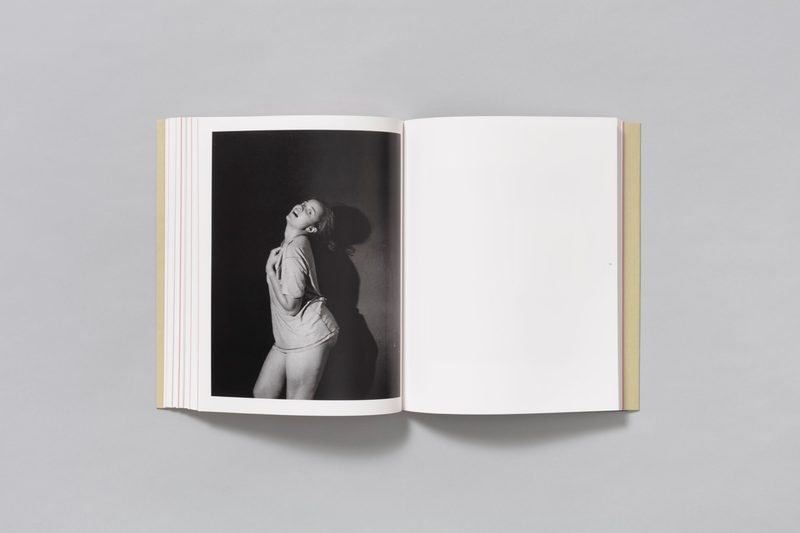

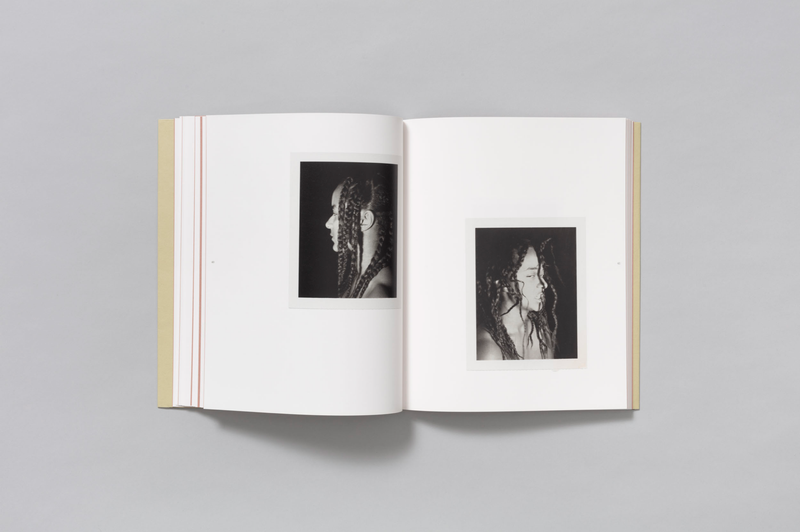

The now published Tender collects pictures Williams took of herself between 1984 and 1999. Going through it, we constantly jump from one year to the other. We move forward and back in time. As the oldest and the most recent merge seamlessly, we enter a space that “follows no chronological impulse” - as Williams points out. A space that stays consistent within, and beyond, time: on the pages of her book, Williams is forever a photography college student in her house, her camera forever on her tripod, her body standing fiercely in front of it. Removing her images from their context and time was something Williams actively seeked for: “It was one of the reasons why I started to take my clothes off for the most part: I didn’t want any specificity of time period. I knew certain iconographies could really date the images, and I wanted to eliminate time as much as possible”.

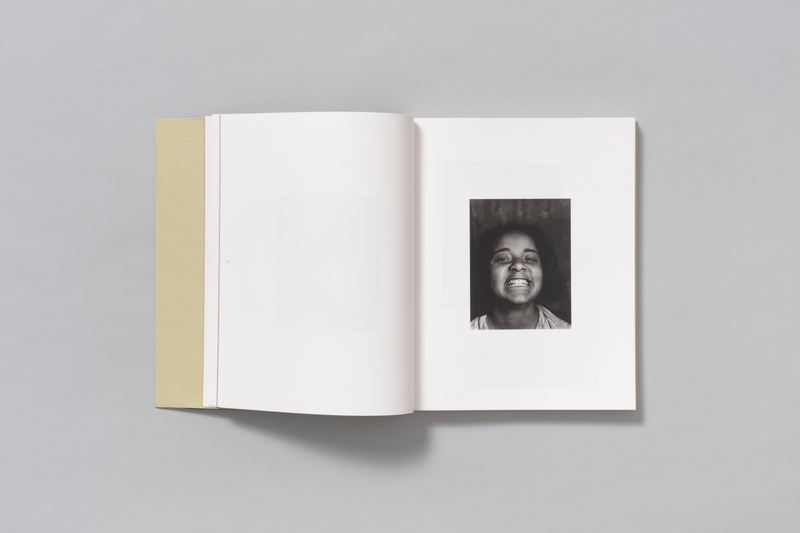

Though, Tender’s photographs don’t necessarily look timeless. At a first glance, they might look more as if they had been shot today. What makes an image contemporary, when it bears no mark of any point in time? In Williams’ photographs, we find a certain disregard for rules. Of what both a body and a photograph should look like - and of the way their encounter should make us feel. There is, to be honest, very little “us”: the need for Williams’ images comes before, and extends beyond, any audience. If her freedom can seemlessly belong to today’s visual discourse, it’s most likely because she didn’t care about anybody else’s eyes except her own. “In the ‘80s, conversations around the male gaze in photography had begun spreading. But I wasn’t driven by that. I had no awarness of projecting my image for anybody else. I just wanted to see my likeness in a photograph. I was completely driven by my relationship to the camera, and by what the camera could do. I was kind of in love with it. I never got tired of it, it was such a routine thing, it was my companion. And I just loved it. I loved the chance of it, shooting and then looking”.

“I really thought that by making all these images”, William says, “I was filling in a gap of something I didn’t see and hadn’t seen before”. What had she seen? The issues of Playboy and Penthouse she would find in her family’s bathroom showed no diversity. The history of photography she would access in Princeton would only portray black women in the context of the Farm Security Administration’s photographic surveys documenting the Great Depression. But Williams had a job in the university library: she would photocopy books for other students. “Except that few people asked for photocopies, first thing. As the photocopy machine was right next to the photobooks, I would just spend my whole shift pulling books off the shelves. Among them was Jean-Paul Goude’s Jungle Fever, and it was the only book that really showed black women. I was obsessed with it, and it wasn’t because of Jean-Paul Goude, but because of Grace Jones. It was all because of Grace Jones! For many years, that was the only kind of experimental, or conceptual representation of black women I had seen. This was pre-Internet, pre- many things. I went from college straight to grad school, in what is in the US essentially a small town, so I wasn’t ever going to be able to see exhibitions. Everything I saw needed to be a reproduction, somewhere”.

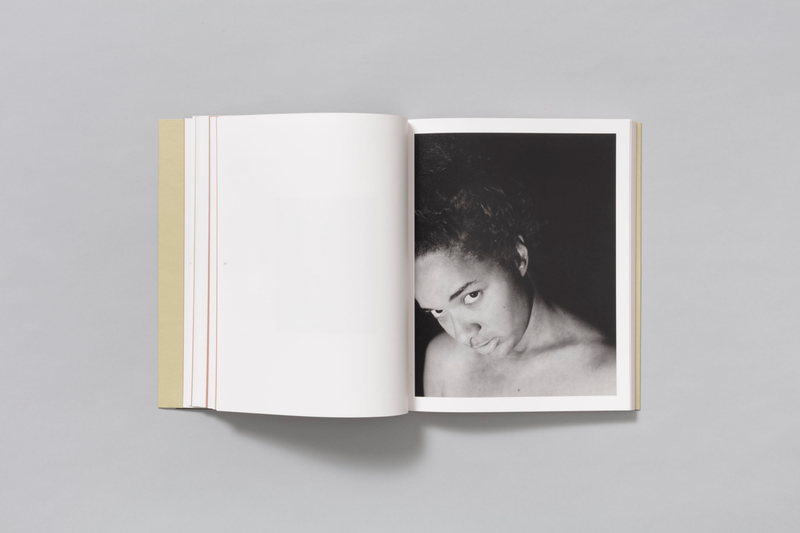

The relationship between a tool for making images and Williams’ body as a young, queer, black woman was a whole new territory to be in. It was equally distant from the photographs she had access to, and from her rather conservative upbringing. As a book, Tender carries a similar sense of discovery. Opening its soft-cover sleeve is unveiling something private. Looking is a privilege, a glimpse into a space that feels more real than reality itself, a truer representation than any mirror. If its poetry is delicate, it also hits you violently at the same time. In the first picture of the book, Williams looks at us sideways, one eye closed, and the other one twisted towards the camera. There’s something uncenny in her gaze - as well as some sort of open challenge. She doesn’t care of what she looks like, her head awkwardly cut in a corner of the image. “It’s just a picture. An image that represents a split second of me. I don’t care - I just love what the camera does. There’s nothing that can bother me in a photograph”, she says.

The importance of that unbothered photograph, the importance of all of this decennal, rather obsessive work at self-discovery is utmost. It’s the urgency of something that was there, and needed 37 years to emerge, reach us, and mess up with our perception of time. As Williams put it, “it was work that needed a lot of different conversations to happen in the meantime, before it could sort of come back around”. Now it's here - and it's for us to carry other, new conversations forward.

--------------

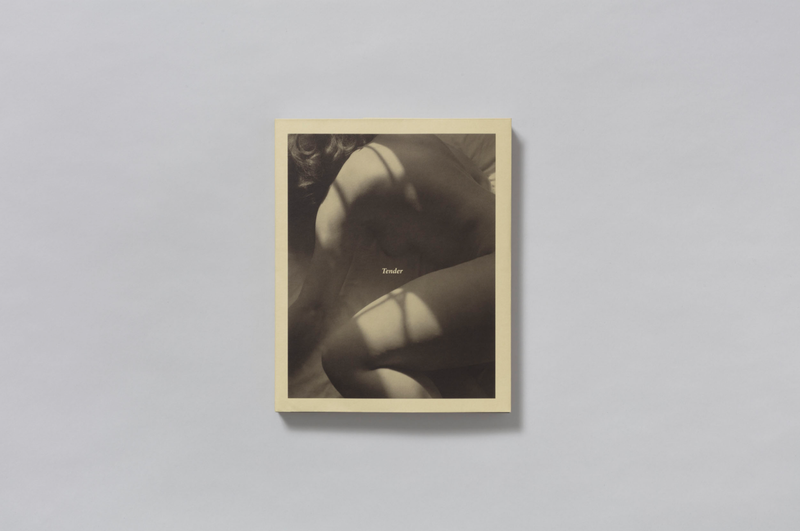

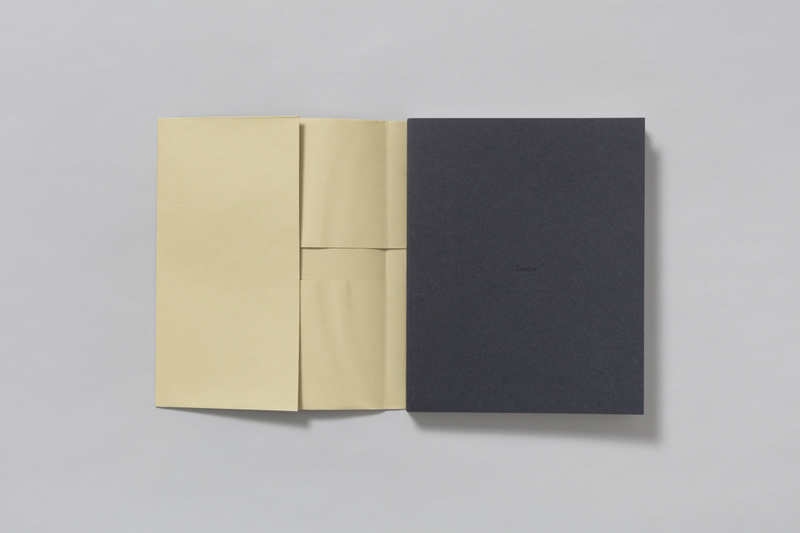

Tender is published by TBW Books

Soft cover with dust jacket

160 pages, 80 plates

8 x 10 in.

Signed and numbered by the artist

Includes an original 4 x 6 inch print

ISBN: 978-1-942953-59-3

--------------

All photos © Carla Williams

--------------

Carla Williams (b.1965) is a writer, editor, and photographer born and raised in Los Angeles, California. She received her MFA from the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and her BA from Princeton University and is the author of numerous essays and articles about photography and co-author of two histories of photography, including The Black Female Body: A Photographic History with Deborah Willis.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based between Italy and The Netherlands, graduated from MA Information Design at Design Academy Eindhoven (NL). Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.